With nearly every feature film at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival reviewed, it’s time to wrap up the first major cinema event of the year. We already got the official jury and audience winners here, and now it’s time to highlight our favorites.

One will find our picks (in alphabetical order) to keep on your radar, followed by the rest of our reviews. Check out everything below and stay tuned to our site, and specifically Twitter, for acquisition and release date news on the below films in the coming months.

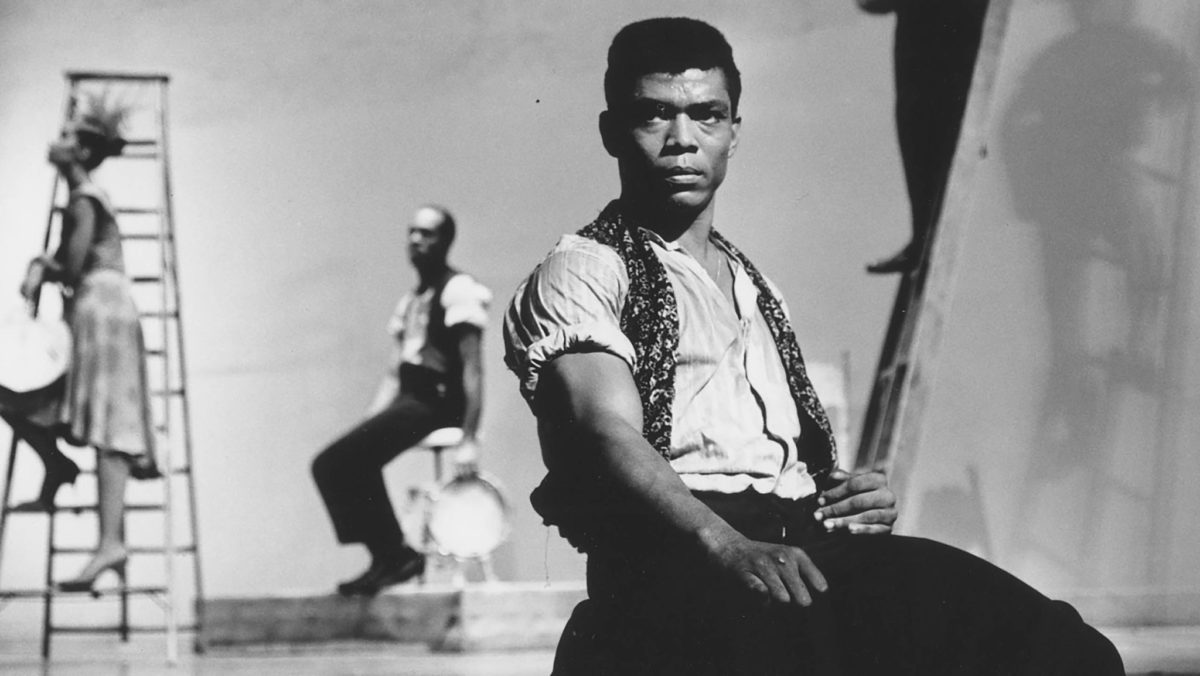

Ailey (Jamila Wignot)

Has any choreographer mattered more to American dance than Alvin Ailey? The documentary Ailey, directed by Jamila Wignot, makes a good case that there has not. Comprised of amazing archival footage, peer interviews, and choreographer Rennie Harris prepping a modern-day performance in honor of the artist, Wignot paints a full picture of a complicated man. Born in the middle of Texas during The Great Depression, old recordings of Ailey recount his picking cotton with his mother (his father was non-existent in his life), then later on seeing Katherine Dunham (and her male backup dancers) perform live. The shock of watching somebody that looked like him produce such wonderful art emboldened him to pursue the work himself. – Dan M. (full review)

All Light, Everywhere (Theo Anthony)

Seemingly birthed from some kind of virtuosic computer algorithm or beamed directly from outer space, Theo Anthony’s debut feature Rat Film was a peculiarly engaging, wholly fascinating documentary. Using the population of rats to chart the history of classism and systemic racism throughout Baltimore over decades, it heralded an original new voice in nonfiction filmmaking. When it comes to his follow-up All Light, Everywhere, Anthony casts a wider focus while still retaining the same unique vision as he explores how technological breakthroughs (and pitfalls) in filmmaking have reverberated throughout history to both embolden and trick our perceptions of perspective. To thread these strands and see its modern-day effects, the majority of the film looks at the engineering behind police body cameras, and the extensive use of those devices and other surveillance equipment to support officers in cases where evidence might otherwise come down to only verbal testimonies. – Jordan R. (full review)

Censor (Prano Bailey-Bond)

It is hard to think of a recent horror film––or a film of any genre, really––in which the main character is tasked with a job as original and ingenious as Enid Baines, the protagonist of Prano Bailey-Bond’s riveting Censor. She is, yes, the titular censor. It is 1980s England, the time of “video nasties” that drew parental consternation and tabloid outrage. These were the low-budget, ultra-violent VHS cassettes that earned their own category in the collective consciousness. Not all were UK productions––I Spit On Your Grave and Abel Ferrara’s Driller Killer made the list. In Censor, however, the nasties are homegrown, in more ways than one. – Chris S. (full review)

Cryptozoo (Dash Shaw)

The current state of American animated cinema is more than a little disappointing; Pixar, Disney, Dreamworks, and more regurgitate the same formula and offer nothing new but a juxtaposition of cartoon designs and hyper-realistic imagery; animation for adults is all too rare. When something like Dash Shaw and Jane Samborski’s Cryptozoo comes along, it’s easy to recognize as one of the most gorgeous works of American animation in ages. – Juan B. (full review)

Faya Dayi (Jessica Beshir)

“Look how far God has brought us. We can only go where God guides us to. We are exactly where God wants us to be.” These are the first words spoken in Jessica Beshir’s ruminative and ravishing feature debut Faya Dayi, and it establishes a conversational dialogue with a higher realm that carries through the rest of this graceful, ethereal journey through Ethiopia. Specifically exploring the trade of the khat leaf––a hallucinatory plant used by Sufi Muslims for religious meditation but has now become Ethiopia’s most lucrative cash crop––Beshir deeply immerses the viewer into daily work, spiritual ponderings, and questions of life’s purpose. At times recalling Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s striking black-and-white debut Mysterious Object at Noon and the vivid chiaroscuro work of Pedro Costa, Faya Dayi shares a similar approach to mixing documentary and narrative elements to form a transportive ethnographic survey. – Jordan R. (full review)

Flee (Jonas Poher Rasmussen)

There have, of course, been a great many animated films about deeply serious subjects, many in recent years, from Persepolis to Anomalisa to Waltz With Bashir. Jonas Poher Rasmussen’s Flee can now comfortably fit on this shelf of profoundly affecting films. Indeed, this 2021 Sundance Film Festival premiere ranks as one of the most uniquely memorable animated films of the last decade. It is remarkably successful as a study of the refugee experience, as a coming-of-age drama set against a backdrop of fear and danger, and as a tribute to one individual’s ability to survive and even flourish. – Chris S. (full review)

Judas and the Black Messiah (Shaka King)

A film that is both timely and timeless, Judas the Black Messiah resists intertwining current events with historical figures––an approach that Spike Lee has excelled at in his work. Instead, director and co-writer Shaka King’s examination of the final moments of Fred Hampton’s short life is grounded firmly in the politics of the late 1960s. It goes without saying that little has changed and therefore it’s easy to connect the dots to recent struggles. – John F. (full review)

Land (Robin Wright)

There is a scene about halfway through Land, directed and starring Robin Wright, in which Miguel (Demián Bichir) reveals a tragedy in his past. Edee (Wright), also grieving, reacts silently and subtlety, though we see so much happening on her face. Nothing said, only felt. It is, truly, a perfect moment captured on film. The kind of thing one will not easily forget. Often actors who step behind the camera will admit that they focused less on their own on-screen performances while directing, sometimes to the detriment of the picture they were making. This cannot be the case here, as Wright the filmmaker wrings out one of Wright the actor’s career-best performances. – Dan M. (full review)

Ma Belle, My Beauty (Marion Hill)

In some relationships it’s easier to pick up where you left off, even after years of being apart. Others, such as those at the core of Marion Hill’s impressive, nuanced feature film debut Ma Belle, My Beauty—contain more heartbreak and baggage. Screening in Sundance’s NEXT category, Hill’s picture navigates uncomfortable truths with perspective and lyrical emotional honestly as Lane (Hannah Pepper) re-enters the life of former lover Bertie (Idalla Johnson) at the request of her husband Fred (Lucien Guignard). – John F. (full review)

Mass (Fran Kranz)

Set in the meeting room of a modest Episcopalian church, two couples meet under tragic circumstances. For his directorial debut Mass, accomplished actor Fran Kranz is determined to wring out four incredible performances from four incredible character actors through the discussion of an extremely tough subject. It is mission accomplished as Kranz succeeds in finding understanding in the unthinkable. – Dan M. (full review)

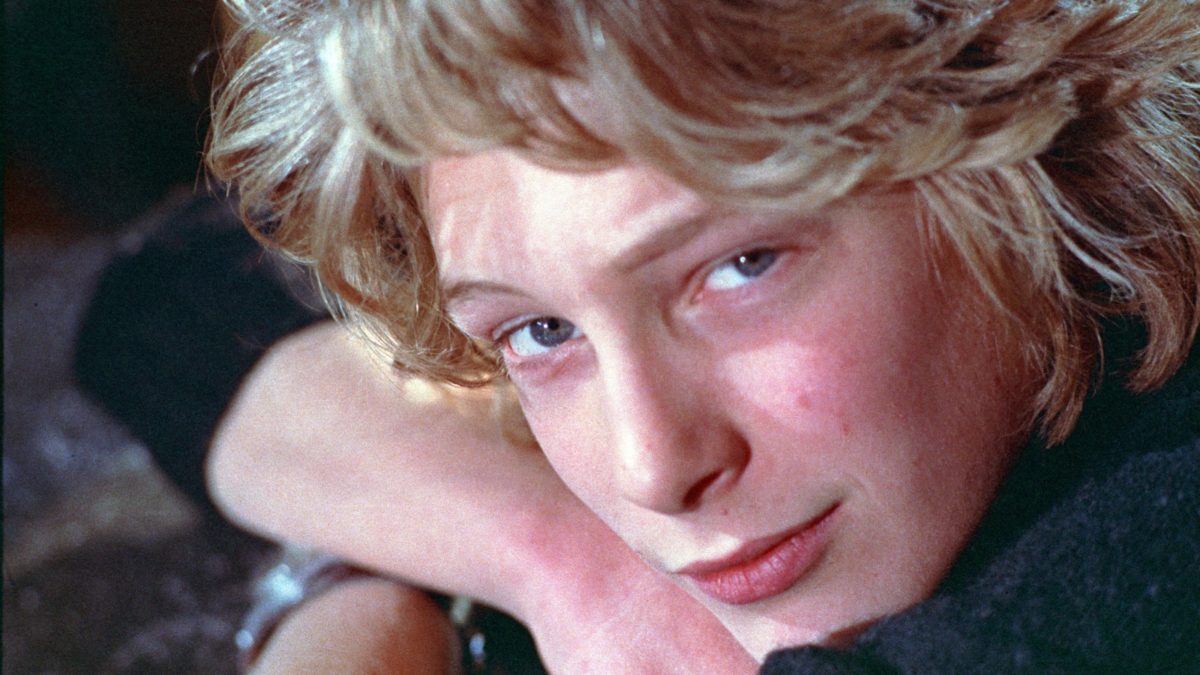

The Most Beautiful Boy in the World (Kristina Lindström, Kristian Petri)

In 1971, Björn Andrésen was the most beautiful boy in the world. In 2019, he’s the elder of a neopagan commune in rural Sweden, whose inability to commit suicide in the fictional ritual of ättestupa forces the other cult onlookers to brutally bash his head in with a rock. In the time between Luchino Visconti’s Death in Venice and Ari Aster’s Midsommar, Andrésen lived a life that might have seemed enviable on the surface, but which he baldly describes in this documentary as a “living nightmare.” It was the fateful casting audition in 1970 Stockholm where Visconti met Andrésen and found his beautiful boy that set the wheels in motion for the rest of his life, marred by personal tragedy, substance abuse, and exploitation. At the film’s conclusion, the woman who oversaw Andrésen’s casting alongside Visconti regretfully reflects on the day that shifted the course of his life forever, unable to separate the years that followed from the first moment this minor was forced out of his innocence. – Brianna Z. (full review)

Passing (Rebecca Hall)

Rebecca Hall’s Passing has been fifteen years in the making, and that dedication shows in every meticulously crafted frame. Adapted from Nella Larsen’s 1929 novel, the tense, black and white psychological drama is a study in intentional filmmaking. Every detail is an obsession with symbolism and performativity, from the by-turns absent and invasive score courtesy of Devonté Hynes to the elaborate period wardrobe from Marci Rodgers, to the affect with which stars Tessa Thompson and Ruth Negga speak. This obsessiveness folds in on itself, creating a layered profile of reunited childhood friends Irene Redfield (Thompson) and Clare Bellew (Negga) whose muffled desire for one another exposes devastating cracks in each of their lives. By turns stifling and lucid with seduction, Hall’s debut is impressive, even when its atmosphere sometimes overtakes its pace. – Shayna W. (full review)

The Pink Cloud (Iuli Gerbase)

Iuli Gerbase’s The Pink Cloud starts off with a disclaimer: “This film was written in 2017 and shot in 2019. Any resemblance to real life is purely coincidental.” Indeed, it doesn’t take long before the uncanny connections between Gerbase’s film and the real-life COVID-19 pandemic become quite unsettlingly clear, in what feels like the simultaneously most accurate and most dystopic depiction of life during a pandemic (namely, during lockdowns of the first part of 2020). In her feature directorial debut, Gerbase’s confident filmmaking intertwined with an all-too-affecting tale of contagion isolation coalesce into a disturbing story of unending, inescapable seclusion on a much larger scale than our initial coronavirus lockdowns. The Pink Cloud suffocatingly explores what it means to live in a world that no longer exists beyond what we artificially create for ourselves, the consequences of extended loneliness, and the capabilities of human adaptation. – Brianna Z. (full review)

President (Camilla Nielsson)

As Americans are painfully aware these days, democracy is messy business. Following her fascinating 2014 documentary Democrats, about the work of creating a new constitution in Zimbabwe, Camilla Nielsson’s sweeping President explores the nation’s second democratic election, in 2018, through the eyes of the opposition party. The legacy of Robert Mugabe looms large in the ruling ZANU-PF party, which controls all manner of life in the nation despite inroads made by the liberal MDC (Movement for Democratic Change) and its presidential candidate Nelson Chamisa. Challenging incumbent Emmerson Mnangagwa, the film shifts modes between fly-on-the-wall picture about the inner workings of a campaign and an on-the-ground study in real election rigging, wherein the ZANU-PF use all manner—from soft approaches like food giveaways to disturbing allegations of sexual violence against poll workers. – John F. (full review)

Sabaya (Hogir Hirori)

Tense and gripping, Hogir Hirori’s documentary Sabaya never positions itself as a thriller. There’s no need. Barring a few cards of scene-setting exposition, this vital dispatch embeds viewers with a rescue operation in the Middle East, and does so with a degree of first-person access that’s not just instantly bold: it’s nerve-janglingly scary. – Isaac F. (full review)

The Sparks Brothers (Edgar Wright)

There’s something to be said for Wright’s sheer admiration of Sparks. He loves this band, a feeling that has clearly lasted for decades. They hold a place in his heart, and now, they have been memorialized forever on the screen. Long after Ron and Russell Mael leave the music industry––if that ever happens, willingly––this film will be available for new fans, old diehards, and the casual viewer surfing a streaming platform. In that way, Wright has given Sparks something they haven’t had in the past: a larger audience. – Michael F. (full review)

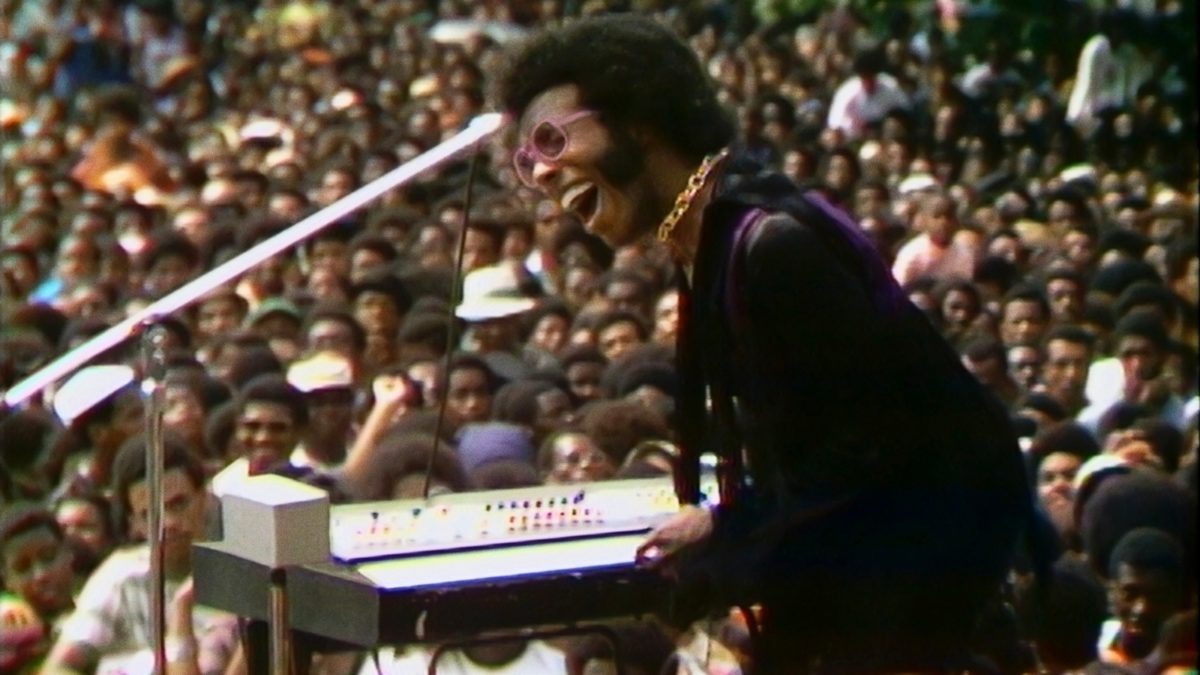

Summer of Soul (…Or, When The Revolution Could Not Be Televised) (Amir “Questlove” Thompson)

The biggest block party of 1969 took place over six weeks in central Harlem. Clustered together into the rocky confines of Mt. Morris Park (now Marcus Garvey Park), 300,000 people spent their summer grooving to a free outdoor concert series that featured some of the world’s best gospel, blues, and R&B singers alive. At the intersection of the country’s racial and social revolution, the “Harlem Cultural Festival” offered a cathartic and electric musical experience for those in attendance, combining song and spoken word that inspired and unified. It was also largely forgotten. Which makes Summer of Soul (…Or, When The Revolution Could Not Be Televised) both a documentary and a rectification of history. – Jake K. (full review)

We’re All Going to the World’s Fair (Jane Schoenbrun)

For the year Sundance goes virtual, it’s inevitable that a few movies play differently than expected. It’s not the most ideal scenario for most projects. Then there’s something like We’re All Going to the World’s Fair that, with its virtual premiere, perhaps plays better than what Jane Schoenbrun could have gotten by showing it at the Ray or the Eccles. Watching it on a laptop just felt right. Watching it alone in the dark was even more appropriate. There’s a connection here. Like the one in the movie, it’s sincere, but it defies categorization. – Matt C. (full review)

Wild Indian (Lyle Mitchell Corbine Jr.)

Wild Indian is a bold, anger-wreaked character study, creating a deeply unsympathetic antihero who nevertheless inspires some pity and understanding. Although representation for indigenous American people in the arts is increasing, it’s still hard to recall a film quite like Lyle Mitchell Corbine Jr.’s debut, which moves its Native American characters from a cinematic periphery they’re most often found towards the center. Its story of an upwardly mobile Ojibwe man (Michael Greyeyes), haunted by a past crime, surprises us, its progression almost like an old-fashioned morality tale, and Corbine feels no pressure to skew to politically correct positive representations. – David K. (full review)

The Rest

Amy Tan: Unintended Memoir (B)

Bring Your Own Brigade (B)

The Dog Who Wouldn’t Be Quiet (B)

A Glitch in the Matrix (B)

In the Same Breath (B)

Jockey (B)

Knocking (B)

Misha and the Wolves (B)

My Name is Pauli Murray (B)

Night of the Kings (B)

On the Count of Three (B)

El Planeta (B)

Playing with Sharks (B)

Son of Monarchs (B)

Strawberry Mansion (B)

Street Gang: How We Got to Sesame Street (B)

Taming the Garden (B)

Try Harder! (B)

Violation (B)

The World to Come (B)

CODA (B-)

Cusp (B-)

Eight for Silver (B-)

Hive (B-)

Luzzu (B-)

Superior (B-)

At the Ready (C+)

Captains of Zataari (C+)

Coming Home in the Dark (C+)

Homeroom (C+)

Human Factors (C+)

I Was a Simple Man (C+)

Mayday (C+)

Pleasure (C+)

Prisoners of the Ghostland (C+)

Searchers (C+)

Marvelous and the Black Hole (C)

Mother Schmuckers (C)

One for the Road (C)

Prime Time (C)

Together Together (C)

First Date (C-)

John and the Hole (C-)

The Blazing World (D+)

In the Earth (D+)

R#J (D+)

Features & Interviews

Must-See Shorts from the 2021 Sundance Film Festival

Fran Kranz on Spirituality in Mass and the Emotional Experience of Making His Directorial Debut

Check back for more interviews and reviews to come!