We don’t want to overwhelm you, but while you’re catching up with our top 50 films of 2020, more cinematic greatness awaits in 2021. Ahead of our 100 most-anticipated films (all of which have yet to premiere), we’re highlighting 40 titles we’ve enjoyed on the festival circuit this last year (and beyond) that either have confirmed 2020 release dates or are awaiting a debut date from its distributor. There’s also a handful of films seeking distribution that we hope will arrive in the next 12 months, which can be seen here.

As an additional note, a number of 2020 films that had one-week qualifying runs will also get expanded releases in 2021, including Nomadland, Gunda, Minari, Dear Comrades!, I Carry You With Me, The Truffle Hunters, Night of the Kings, One Night in Miami, Pieces of a Woman, and Herself.

About Endlessness (Roy Andersson)

“What should I do now that I have lost my faith?” is the question that animates About Endlessness; this being the new film by Roy Andersson, it is delivered in a doctor’s waiting room, over and over again, in a creaky voice, by a dumpy man in late middle age who continues his plaint even after the doctor and his receptionist gruntingly force him outside into the hallway, from whence they can hear him scratching at the door like a zombie. About Endlessness is Roy Andersson’s fourth film of this century; it looks much like the previous three, and nothing like anything else ever made. – Mark A. (full review)

Acasa, My Home (Radu Ciorniciuc; Jan. 15)

When encountering the societal and economic structures of everyday life, it’s not a rare dream for many to wonder what life may look like off the grid and out of the hands of a bureaucratic entity that doesn’t have your best interests in mind. For one family living in the vast water reservoir of the Bucharest Delta, they have made this their reality for the last eighteen years. The Enache family and their nine children call this abandoned area their home, sleeping in their homemade hut, fishing for food, and taking gentle care of this slice of nature directly outside the hectic Romanian capital. As outside interest in their homeland grows, Acasă, My Home director Radu Ciorniciuc captures the forces of civilization that cause an upheaval of their lives with a well-rounded eye, painting an empathetic, complex portrait of the costs of independence. – Jordan R.

Anne at 13,000 ft (Kazik Radwanski)

Anne (Deragh Campbell) is in stasis. Doing four shifts a week at a Toronto daycare, she’s repeatedly given a hard time by co-workers (or the managerial state in general) for being “unprofessional,” i.e. daydreaming or playing too much with the kids. Perhaps a reflection of how many of us reach a certain point, say in our late 20s, where we realize that we’re not going to actually be made happy by our career. Beyond struggling at work, Anne’s interactions with friends, family, and Tinder dates alike all take on different plains of awkwardness; she struggles to maintain conversation, a straight face, or even a line of thought. – Ethan V. (full review)

Apples (Christos Nikou)

Apples is set in a world where digital technology seems not to exist, yet the psychic imprint of the digital age hangs heavy over first-time director Christos Nikou’s sparse absurdist dramedy. In an alternate-universe Greece, people are falling victim to a pandemic of sudden-onset Memento syndrome: total, crippling amnesia that befalls ordinary adults seemingly at random, necessitating elaborate state-run medical programs for the mnemonically impaired. Of particular concern to such programs are “unclaimed” amnesiacs, patients who fail to be identified by friends or family members and thus become wards of the state, who must be gradually rehabilitated into society and construct new identities from scratch. – Eli F. (full review)

Atlantis (Valentyn Vasyanovych; Jan. 22)

In Valentyn Vasyanovych’s post-apocalyptic Atlantis, the sky above Ukraine hangs like a sheet of steel, a uniform mass of clouds bucketing water onto the mud-covered wasteland down below. The year is 2025, and the country has just emerged victorious–if shattered–from a war with Russia. It’s a conflict all too steeped in the decade’s real-life skirmishes between Ukraine and its neighbor to come across as strictly fictional, and that’s the thing that makes Atlantis so disturbing. It’d be tempting to call Vasyanovych’s a dystopia, were it not for that fact that, all through its 108 minutes, everything about it feels almost unbearably vivid–closer to some news report or a post-conflict documentary than any artificial rendition thereof. There are soldiers gingerly plucking mines out of fields, foreign NGOs fretting about the country’s recovery, unidentified corpses exhumed and re-buried, and shell-shocked veterans struggling to find their way back into civilian life. – Leonardo G. (full review)

Beginning (Dea Kulumbegashvili)

Originally a Cannes selection, then coming to San Sebastian, TIFF, and NYFF where it picked up deserved awards, the Georgian film Beginning is a difficult, sometimes brutal film to watch and then unpack. Déa Kulumbegashvili’s debut is a look at the confines, both religious and familial, put on one woman’s (Ia Sukhitashvili) life as she wrestles with outer and inner demons. Both a lonely and patient film, Beginning acts as mirror and portal, creating turmoil and strife for audience and subject. Challenging yet rewarding, Beginning is phenomenal. – Michael F.

Days (Tsai Ming-liang)

Not a huge amount takes place at the beginning of Days. The opening exchanges are elemental: wind blows; rain patters; grass shivers; a boy in pink shorts plays with fire. But then not a huge amount happens after. The movie is the latest from director Tsai Ming-liang, a Malaysia-born filmmaker and master of slow burns; and a key figure in the second wave of Taiwanese New Cinema. What Tsai does do–and better than most–is long takes; beautiful compositions; urban bustle; gorgeous color; neon light–as well as capture touch, sexuality and the human body. – Rory O. (full review)

Derek DelGaudio’s In & Of Itself (Frank Oz; Jan. 22)

It’s a tough act for a critic to try and explain the joys and pleasures of Derek DelGaudio’s In & of Itself. In short, it’s an evocative exploration of narrative and identity through magic and trickery, starting with a thesis statement: we are all our own unreliable narrators. While this premise could also be a trigger warning at the beginning of Rashômon, Shutter Island, and a few Fincher films, In & of Itself takes a fascinating turn, steeped in the kind of narrative that’s required at the heart of every magic show. Objects are given meaning, including a gold brick that appears on stage and around the city of New York, symbolizing a brick thrown into the window of his childhood home after his mom came out. – John F. (full review)

Ema (Pablo Larraín)

Movies have been named after far less interesting forces than the protagonist of Ema. Played with unblinking gravitas by the Chilean television actress Mariana Di Girólamo (a remarkable find), Ema is a contemporary dancer who stalks the neon lit streets of the Chilean port city of Valparaíso in track bottoms, cropped leopard-print tops, and slicked back peroxide blonde hair. She also has a propensity for arson. In the film she leaves her partner Gaston–who is the choreographer of her dance troupe (and also maybe gay)–in order to dance to Reggaeton hits on a rundown tarmac football pitch. The film is utterly infatuated with her. – Rory O. (full review)

Film About a Father Who (Lynne Sachs; Jan. 15)

While director Lynne Sachs admits her latest documentary Film About a Father Who could be superficially construed as a portrait (the title alludes to and the content revolves around her father Ira), she labels it a reckoning instead. With thirty-five years of footage shot across varied formats and devices to cull through and piece together, the result becomes less about providing a clear picture of who this man is and more about understanding the cost of his actions. Whether it began that way or not, however, it surely didn’t take long to realize how deep a drop the rabbit hole of his life would prove. Sachs jumped in to discover truths surrounding her childhood only to fall through numerous false bottoms that revealed truths she couldn’t even imagine. – Jared M. (full review)

French Exit (Azazel Jacobs; Feb. 12)

At a glance, Azazel Jacobs’ French Exit seems trivial, especially at a time when billionaires exist in droves, and the wealth divide continues to drastically widen. As the director’s second official collaboration with novelist and screenwriter Patrick deWitt, the closing film of the New York Film Festival cannot be confined to its logline: “A close-to-penniless widow moves to Paris with her son and cat, who also happens to be her reincarnated husband.” Opening with a written, serif font title card, the oddly upbeat, piano-heavy score whisks you into a world of lost riches, lost husbands, and lost relationships. Jacobs’ sixth feature is consumed with these oddities, contradictions, and absurd moments, consumed by the idea of a good, hearty laugh based on the melancholy of one’s circumstances. – Michael F. (full review)

The Human Voice (Pedro Almodóvar; March 5)

Short work by great directors is customary at major festivals, but most often it underwhelms. Not here. Perhaps it’s because this is a project with special resonance for Almodóvar. The Human Voice, Jean Cocteau’s one-act, one-character monodrama has echoed across the Spanish great’s career. It’s directly referenced in Law of Desire and informs the plot of Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown. And Almodóvar’s own debut work in the English-language has been a long-delayed event––past projects he was touted for include Brokeback Mountain and The Paperboy (a bullet dodged?). Tilda Swinton, key collaborator of the greatest working filmmakers, plays the unnamed woman teetering on the verge of yes, a breakdown, but one eventually focused into cataclysmic external force. – David K. (full review)

Identifying Features (Fernanda Valadez; Jan. 22)

The winner of the Audience Award and Best Screenplay in the World Cinema (Dramatic) section at Sundance Film Festival last year, we recently caught up with Identifying Features at New Directors/New Films last month. Mark Asch said in our review, “The original Spanish-language title of Identifying Features is Sin Señas Particulares, or “No Particular Signs”—a reference to the individuating marks found, or not, on unclaimed corpses found near the U.S.-Mexico border. It’s an echo of Sin Nombre (“Nameless”), Cary Joji Fukunaga’s vivid immigration-thriller debut from 2009, and an apt title for a film that takes a fresh look at lives erased and distorted by migration and violence. Though Trump-era border policy is an implicit backdrop to the cartel activity and mass abductions she depicts, debuting director Fernanda Valadez’s zoomed-in perspective is on family trauma, not imperial culpability.”

The Inheritance (Ephraim Asili; March 12)

An early favorite for one of the best directorial debuts of 2021, Ephraim Asili’s The Inheritance places its audience inside a Black activist collective in Philadelphia as the director explores both the traumatic history of the liberation group MOVE and a brighter path ahead through radical action. Insightful as it pertains to the power of collective artistry and activism, it’s also a genuinely entertaining film as Asili, borrowing from his own experience, recreates a housing scenario that brings an unexpected dose of humor. – Jordan R.

Just Don’t Think I’ll Scream (Frank Beauvais; Jan. 29)

After watching over 400 films in the span of just around four months, director Frank Beauvais reflects on his life and what led to this cinematic hibernation in Just Don’t Think I’ll Scream, an impressive, rapidly-edited, and deeply personal cinematic essay. Created solely from clips of the films he watched, it’s far from the kind of video essays that dominate YouTube, rather selecting the briefest of moments, and usually the least-recognizable of shots, in crafting this self-exploration of a reflective, questioning mind.

The Killing of Two Lovers (Robert Machoian; Feb. 23)

Opening with a jarring, heart-stopping scene in which David (Clayne Crawford) points a gun at his sleeping wife, Robert Machoian’s The Killing of Two Lovers is a riveting and restrained autopsy of a marriage in free fall. David and Nikki (Sepideh Moafi) have already separated, with David returning to his parent’s home. Their teenage daughter Jessica (Avery Pizzuto) takes it out on both parents, telling them to be the adults and work it out. The problem with that notion is that David and Nikki never had the chance to grow. Having Jessica young and four boys immediately afterward, they’ve stayed in the same small Utah town and moved only a few doors away from David’s childhood home. – John F. (full review)

Lapsis (Noah Hutton; Feb. 12)

As we close the books on 2020 and turn towards a new year, one of the first essential sci-fi features to seek out is Lapsis, a selection at SXSW last year that will now arrive in February. Written and directed by Noah Hutton, with a cast featuring Dean Imperial, Crashing stand-out Madeline Wise, Babe Howard, and Arliss Howard, the film is set in an alternate present of NY where the quantum computing revolution has begun. The story centers on a Queens delivery man who becomes a “cabler” in this gig economy to connect miles of infrastructure needed to have the quantum trading market succeed. Read Jared Mobarak’s review from Nightstream here.

Little Fish (Chad Hartigan; Feb. 5)

Following his breakout film This is Martin Bonner and his vibrant follow-up Morris In America, director Chad Hartigan had prescient, ambitious goals for his next feature while still retaining an eye for character-focused drama. Set during a global pandemic in which a portion of the population is affiliated with memory loss, Little Fish tenderly follows the relationship between a couple (Olivia Cooke and Jack O’Connell) as they must face this scary new world and the personal strife it contains. As Hartigan elegantly jumps between the past and the present, he reckons with the universal fear of having those closest to you drift away. – Jordan R.

Isabella (Matías Piñeiro)

Women from Shakespeare’s oeuvre find themselves reincarnated in modern-day South America through the recent works of Argentine director Matías Piñeiro (Hermia & Helena, The Princess of France, Viola), which operate with non-linear structures concentrated on the intersection between the professional and intimate lives of actresses or aspiring artists. His unassumingly sumptuous new feature Isabella–which channels the central sister-brother dilemma in the British author’s Measure for Measure–examines two women’s unexpressed self-doubt, their aversion to risk, and conflicted career aspirations in an initially puzzling but ultimately rewarding fragmented narrative. – Carlos A. (full review)

Joe Bell (Reinaldo Marcus Green; Feb. 19)

The first event at which we see Joe Bell (Mark Wahlberg) speak his anti-bullying message can’t help but make you laugh. He’s standing on-stage with a disheveled look cultivated by a weeks-long journey on foot, spouting more nervous “ums” then concrete dialogue as his son Jadin (Reid Miller) watches at the back of the auditorium. The scene lasts less than two minutes before Bell asks the audience of teenagers if they have any questions as though his awkward presence was enough to spark conversation let alone change. It’s the epitome of performative allyship and self-assuaging action that can often do more harm than good. An empty speech won’t inspire people to embrace a cause. It will instead embolden the intolerant into believing their opponents have nothing to say. – Jared M. (full review)

Los Conductos (Camilo Restrepo)

Succinctly potent like a concentrated shot of a mood-altering substance, Camilo Restrepo’s Los Conductos renders a Colombian portrait of a damaged soul reclaiming his humanity amidst widespread bleakness. In a swift 70 minutes, the lugubriously solemn film punctures one’s psyche as it interrogates a society’s moral corrosion that has normalized violence as the lone avenue to salvation for the marginalized. – Carlos A. (full review)

Mandibules (Quentin Dupieux)

Like the giant fly in Mandibules, director Quentin Dupieux has been buzzing and provoking us for roughly the past decade, trying to build a reputation as a new French surrealist auteur. Many were won over by last year’s Deerskin, buthis latest bizarre creation truly confirms his talent. His two best-known features, Rubber and the aforementioned Deerskin,can be summed up in a simple high-concept phrase: respectively, the “killer tire film” and the “killer jacket film.” In surrealist logic, the evolutionary chain clearly goes from tire to scream (Reality) to jacket and now to fly. Rather than something out of Cronenberg’s beloved remake, this fly is a charming, almost Spielbergian creature––far less dangerous than its human cast members. The film is notable for finding different sources of humor, puerile as they may be, than his usual theatrical violence. – David K. (full review)

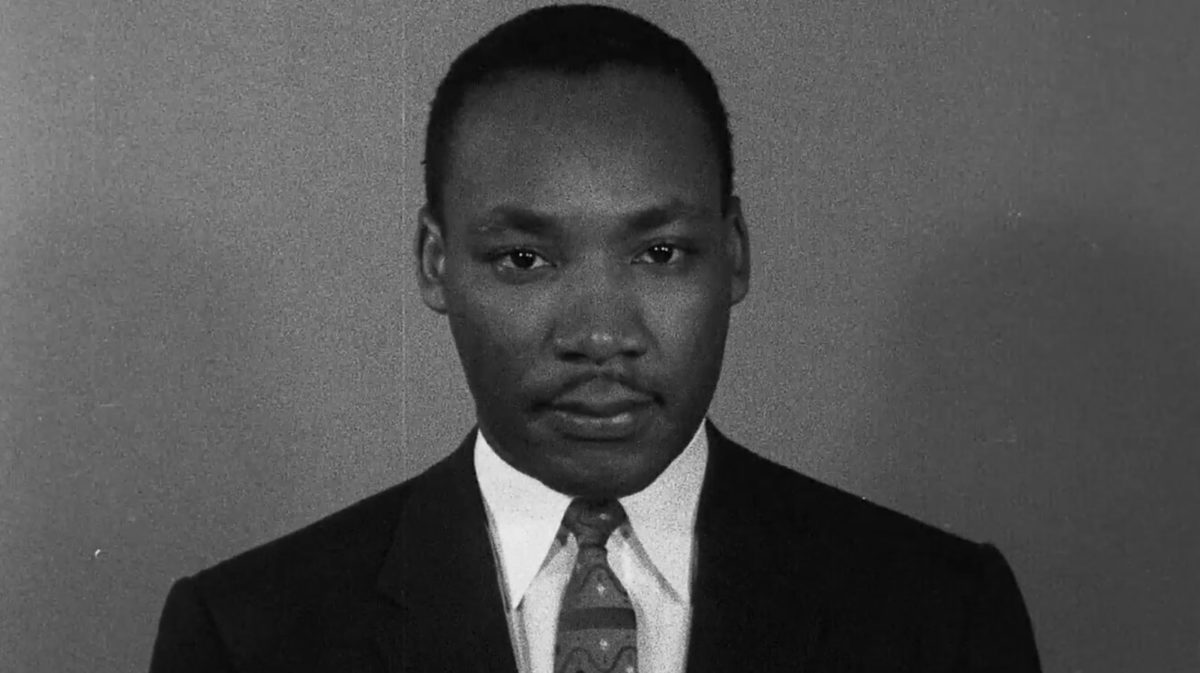

MLK/FBI (Sam Pollard; Jan. 15)

Sam Pollard’s concise new documentary wrestles with King’s legacy as a Black Christian-pacifict freedom fighter and philanderer. If the last noun makes you tense up, the documentary is doing its job. The FBI’s ruthless campaign to discredit MLK Jr. with dirt on his affairs is at the center of Pollard’s story. It poses two questions: do King’s affairs discredit his legacy? And was J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI acting outside the bounds of the law, or as an apparatus of the political order? Using research from David J. Garrow, a Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer of Dr. King, testimonials from King’s inner circle, and recently declassified FBI documents, MLK/FBI shows––despite the FBI’s best efforts––the substance of King’s legacy is not his affairs, but his righteous cause for equality. – Josh E. (full review)

Notturno (Gianfranco Rosi)

The reaction to Notturno is going to be as interesting to observe as the work itself, and it begs to be further contextualized by experts on the Syrian Civil War and ISIS. The stellar documentary further confirms Gianfranco Rosi’s mastery of his chosen form: concise narratives of ordinary people captured in their environments––often those afflicted by broader conflicts––and all depicted through precise still compositions that double as formally polished photojournalism. – David K. (full review)

The Perfect Candidate (Haifaa Al-Mansour)

It’s extremely difficult to make a film that’s intelligent, political, and crowd pleasing, but Haifaa Al-Mansour pulls it off with her fourth and most accomplished feature to date. The Perfect Candidate follows Maryam, a female doctor in Saudi Arabia, as she runs for local office. I love that the film refuses to paint anyone as a villain; even well-meaning men can do little to help Maryman, because they’re also operating within a patriarchal system. – Orla S.

The Reason I Jump (Jerry Rothwell; Jan. 8)

An immersive documentary, Jerry Rothwell’s The Reason I Jump places us internally within the mind of the nonverbal autistic, allowing empathy to flow in. Inspired by Naomi Higashida’s groundbreaking book, written when the author was just 13, the film is a transcendent experience often operating in a poetic mode as it explores the complexities of understanding how the universe is ordered. The text, adapted into English by David Mitchell and K.A. Yoshida, unpacks the process of perception of its author, including how he deduces it is raining. – John F. (full review)

Rose Plays Julie (Christine Molloy and Joe Lawlor; March 19)

Get ready for a tense ride because writers/directors Christine Molloy and Joe Lawlor’s Rose Plays Julie never relinquishes its sense of brooding until the very last frame’s welcome exhale of relief. Why should they considering the subject matter? This is a dark story dealing with a reality too many women have experienced without the means for guaranteed justice. So while it might be a spoiler to say, I’m not sure it’s possible to speak about the film without mentioning how everything we witness is the result of a rape that occurred two decades previously. That event led to Rose’s (Ann Skelly) birth. It forced Ellen (Orla Brady) to explicitly state that she did not want her daughter to ever reach out. And its shared pain drives them today. – Jared M. (full review)

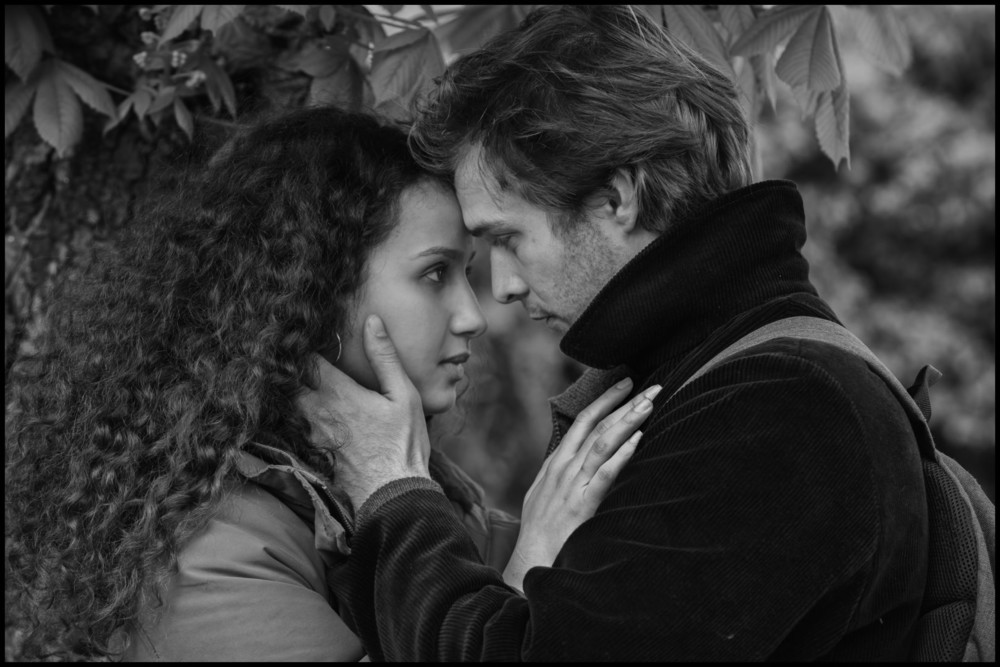

The Salt of Tears (Philippe Garrel; Jan. 20)

If anything, what Garrel’s film lacks in emotional connection it gains in reserved reflection. It’s a study in male chauvinism, and yet these characters–both men and women–are adults, in adult relationships, whose responsibility is theirs alone. There’s something generous in that type of filmmaking–no anger, just disappointment, with the lingering melancholy that nobody’s actions in life are perfect. – Ed F. (full review)

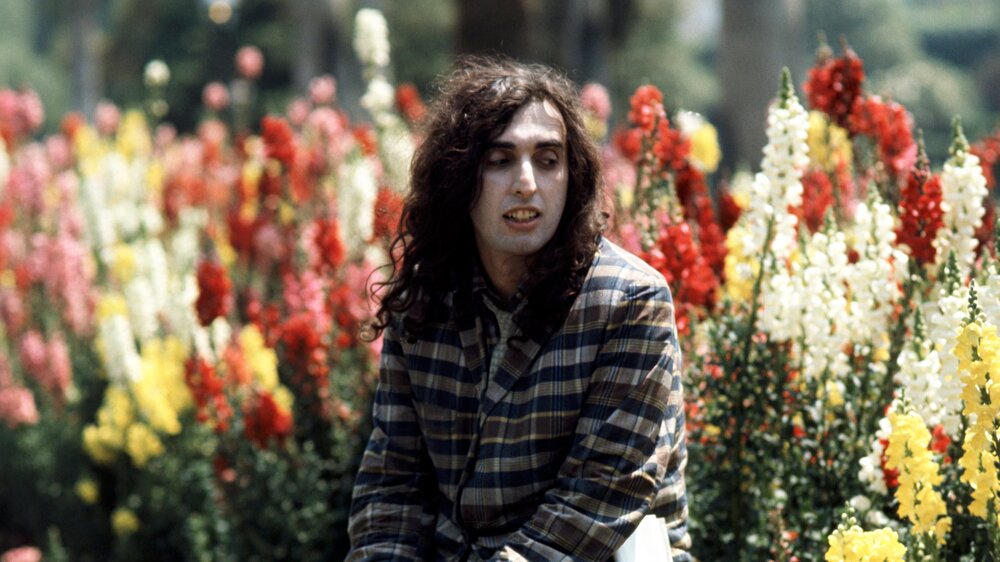

Saint-Narcisse (Bruce LaBruce)

Leave it to Bruce LaBruce to take the Narcissus myth and adapt it into a soapy twincest drama. Set in 1970s Canada, Saint-Narcisse follows the journey of a young, attractive, self-obsessed man who discovers he has a long-lost twin brother living in a monastery. Twists and turns abound, leading to a funny, blasphemous, and sincere (!) love story of an unconventional family unit. If anything, Saint-Narcisse is a nice reminder that it’s possible to be provocative and have fun at the same time. – C.J. P.

Shiva Baby (Emma Seligman)

It is apropos that Emma Seligman’s Shiva Baby is screening in the Toronto International Film Festival’s Discovery platform. It is a discovery, in every sense: the discovery of a new comic voice behind the camera, the discovery of a note-perfect star in lead actor Rachel Sennott, and the discovery of a viewing experience that is at once hilarious, awkward, uncomfortable, and unforgettable. Shiva Baby is a blast of energy and from its first moment to its last Seligman finds the right balance. There is genuine suspense, if not horror; the score, by Ariel Marx, could just as easily fit a summer camp slasher flick. But the greatest feeling for the audience––after discomfort––is excitement. – Chris S. (full review)

Supernova (Harry Macqueen; Jan. 29)

How can one begin to contemplate losing the person they love most in the world? It’s difficult to think about and often, as human beings, we put off the future realities of loss and grief until it’s too late to run from them. We are all going to die and part of life is watching it happen to the people we love, whether it’s a sudden shock or the slow process of witnessing them lose themselves. It’s the hardest thing in the world to cope with for many, harder than the prospect of our own deaths. How do you live with the knowledge that you’re going to outlive your partner? That’s one of the main questions that Supernova, the affecting new drama from Hinderland director Harry Macqueen, poses to its audience. – Logan K. (full review)

There Is No Evil (Mohammad Rasoulof)

Iranian director Mohammad Rasoulof won Cannes’s Un Certain Regard award in 2017 with his bruising, brilliant drama A Man of Integrity, which explored how an oppressive regime crushes independent thought. On his return to his home nation, he was arrested, thrown in prison for a year, banned from leaving Iran, and forbidden from filmmaking for life. Not that it stopped him. Just three years later, he’s made a major work of recent Iranian cinema. Not since A Short Film About Killing has a filmmaker produced such a thrilling case against capital punishment, an enraging, enthralling, enduring testament to the oppressed. – Ed F. (full review)

Tiny Tim: King for a Day (Johan von Sydow)

King for a Day is an energetic, wildly creative account of an inimitable figure who lived an almost unbelievable life. It features interviews with a wildly diverse mix of friends and collaborators––Peter Yarrow, Tommy James, Wavy Gravy, D. A. Pennebaker, Jonas Mekas (!)––and Weird Al Yankovic as the voice of Tiny Tim’s diary entries. Director von Sydow employs haunting animation and stunning archival footage to craft a film as insightful as it is entertaining. – Chris S. (full review)

True Mothers (Naomi Kawase; January 29)

Naomi Kawase is a divisive name on the festival circuit, though you might be surprised that’s the case when actually watching her work. A mainstay at the Cannes Film Festival for over two decades, Kawase boasts fluidity in form and feeling. She blends documentary and fiction while putting her stories within a context that reveres the natural world, an approach that has inspired admiration for some and annoyance for others. But whatever one accepts or rejects from Kawase’s films is irrelevant to the fact that she has a distinctive voice, and the way her vision adapts to or clashes against cinematic conventions can be a rewarding experience in itself. True Mothers, Kawase’s adaptation of a novel by Mizuki Tsujimura, might be her most plot-heavy work to date. – C.J. P. (full review)

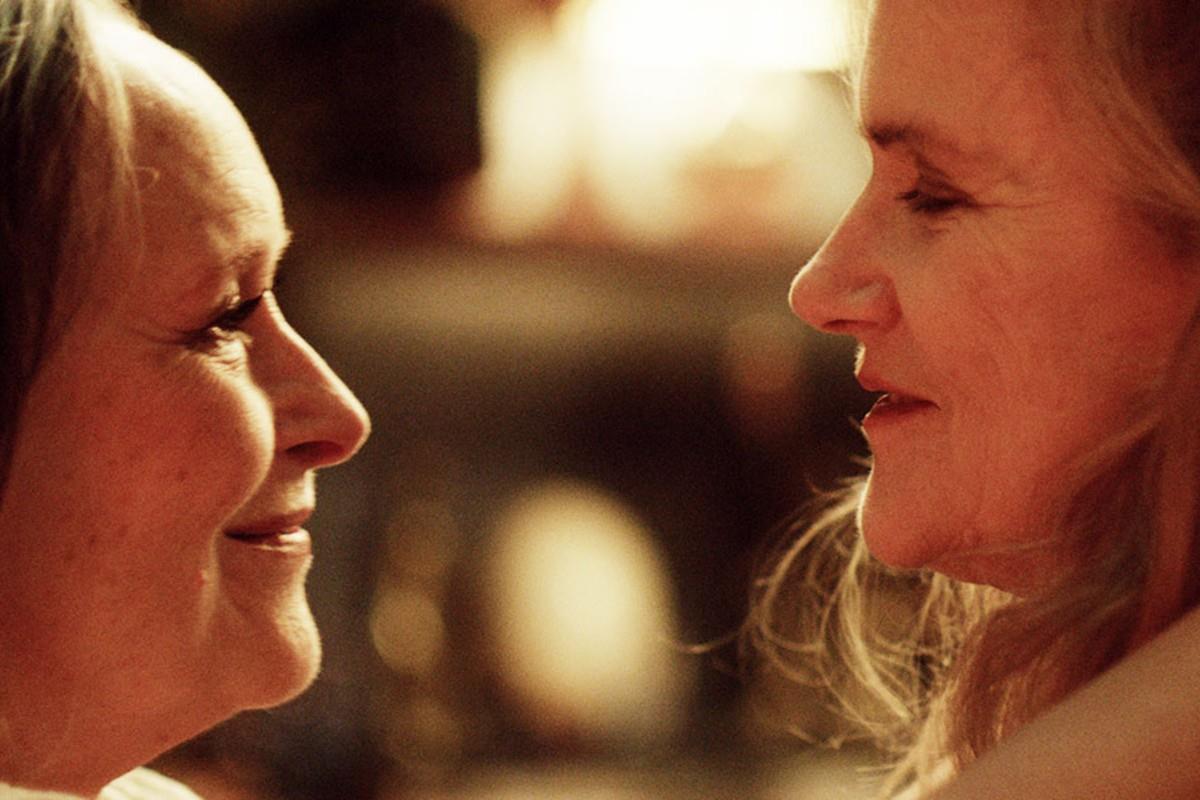

Two of Us (Filippo Meneghetti; February 5)

When Two of Us begins, we meet Nina (Barbara Sukowa) and Madeleine (Martine Chevallier) a couple whose comfort with each other is palpable through their silences, a way of intimate communication only developed through years of relationship. As they discuss their plans to relocate from France to Rome while talking about children, we first assume they have always been together, and are finding a way to break the news to the kids. As Nina becomes a bit more impatient, reminding Madeleine she needs to take care of herself as well and that her children are adults, we wonder: is she their stepmom? – Jose S. (full review)

Undine (Christian Petzold)

Following up a successful work of lucid experimentation like Transit can be a tricky undertaking: does one lean back toward the basics or further up the ante? Christian Petzold shoots for the latter with his latest, a Berlin-based pseudo-supernatural melodrama titled Undine. And that name should prove telling: the myth of the watery nymph that inspired as far-flung old guys as Walt Disney, Andy Warhol, Neil Jordan, and Hans Christian Andersen in their creative endeavors. Ever the intellectual, in his press notes Petzold references the female-centric version of Ingeborg Bachmann as his key inspiration and his story does prove, for the most part, to be told from the eponymous heroine’s angle. – Rory O. (full review)

Violation (Dusty Mancinelli and Madeleine Sims-Fewer)

We’re often told growing up that every story has two sides so that we can learn how to put ourselves into another’s shoes and see whether actions we thought were harmless actually did cause harm. That doesn’t mean you can’t project the sentiments onto adult situations too, though. Especially when they deal with memory. Take Miriam (Madeleine Sims-Fewer) and Greta (Anna Maguire) for example—two sisters who used to do everything together in their youth. When the topic of teenage injustice first arrives in conversation, their anecdote is colored as Big Sis defending the honor of Little Sis. When it comes up a second time, however, Greta reminds Miriam that she specifically asked her not to do what she did because of the consequences that did ultimately arise. – Jared M. (full review)

Wife of a Spy (Kiyoshi Kurosawa; Spring TBD)

We’re in Kobe in 1940 on the eve of war. An English businessman is being forcefully ejected from his factory by a group of soldiers. “What has become of Japan?” he asks despairingly. So plays the opening sequence of Wife of a Spy, a world-weary wartime romance from Japanese filmmaker Kiyoshi Kurosawa about an affluent married couple who each must ask themselves a thorny question. Their country is at a crossroads, how best to respond? – Rory O. (full review)

The Woman Who Ran (Hong Sangsoo)

The Woman Who Ran opens on a lovely shot of hens. The camera then pulls back to show the garden of a middle-class apartment block where a woman named Youngsoon (Seo Younghwa) tells another, Youngji (Lee Eunmi), about her hangover. The lighting is natural; the performances and sentiment are, too. Hong Sang-soo’s cinema is one of repetition and anyone familiar will not take long to discern The Woman Who Ran as his own. He rinses; he washes; he repeats. – Rory O. (full review)

The World to Come (Mona Fastvold; Feb. 12)

In The World to Come, an unlikely romance blossoms against the rugged rural backdrop of the American Northeast. The action plays out during the year 1856 somewhere in the region of Syracuse, a few years shy of the American Civil War. The setting could hardly be more isolated; the living much further from easy. On January 1st, our lonesome protagonist welcomes the changing of the calendar with the bleakest of resolutions: “With little pride and less hope, we begin the new year.” – Rory O. (full review)

Zola (Janicza Bravo; June 30)

Twitter is Shakespeare for the 21st century and, as Zola proves, Janicza Bravo is the director best adept at bringing all the peculiarity, hilarity, and ugliness of social media mayhem to the big screen. If you were on Twitter in October 2015, you likely saw A’ziah “Zola” King’s massive thread recounting the bizarre journey she took from Detroit to Tampa accompanied by Jessica, a new acquaintance that wanted to utilize their pole dancing skills to make serious money in Florida strip clubs. What follows was a treacherous two-day adventure of turning tricks, one-upping pimps, witnessing a murder, attempted suicide, and no shortage of strange characters. Based on Zola’s 150 or so tweets and David Kushner’s Rolling Stone article (which revealed some of the story was embellished for the sake of entertaining storytelling), Bravo and co-writer Jeremy O. Harris (Slave Play) have now delivered a surprisingly faithful adaptation while bringing endless invention and energy to the proceedings. – Jordan R. (full review)

Also Opening in 2021