After highlighting the most overlooked films of 2020, today we’re putting a spotlight on the films that need a home to be seen in the first place: the 40 or so films (and honorable mentions) that we loved on the festival circuit that are still seeking U.S. distribution.

Acting also as a 2020 preview, we hope that highlighting these titles spurs some distributor interests and a release in the next twelve months. Featuring favorites from Berlinale, SXSW, Sundance, TIFF, NYFF, Rotterdam, and beyond, make sure to follow us on Twitter to get the latest distribution updates. As we move into 2021, one can also track all of our upcoming festival coverage here.

200 Meters (Ameen Nayfeh)

In a time where the Israeli occupation of Palestine is still causing the deaths of children, the separation of families, and the oppression of Palestinian citizens, a film like 200 Meters becomes even more necessary and relevant. Following a Palestinian father desperate to get to his ill son in spite of the obstacles of the Israeli regime, the film manages to showcase the horrors of structural oppression without ever crossing into misery porn. While there isn’t any healing for decades of trauma by the end, beauty and love can still be embraced. – Logan K.

After Love (Aleem Khan)

The idea your loved ones aren’t who you thought they were is an anxiety that looms over many people. Even after decades of love, the fear of an untold truth can haunt and infect a relationship. In After Love, the realization of deceit and heartbreak comes after death, where grief becomes a display of missing the person you loved and the person you never knew. As the incredible Joanna Scanlan grows closer to accepting the truth of her husband’s life, a feeling of profound melancholy washes over you. A challenging and deeply emotional film. – Logan K.

The Atlantic City Story (Henry Butash)

Despite a relatively unassuming title, Henry Butash’s ruminative feature debut, The Atlantic City Story, is a quietly profound, muted character study, following two wayward souls at a crossroads in their lives, looking to the faux-glamour of Atlantic City as a possible escape. While hitting familiar narrative beats, the film features a career-best performance by notable character actor Jessica Hecht and relative newcomer Mike Faist (perhaps most famous for his work in Dear Evan Hansen), marking an auspicious debut for the first-time director. – Christian G. (full review)

The Calming (Song Fang)

The most fitting title of the year, The Calming is a serene, gorgeously photographed journey through Japan, China, and Hong Kong as we follow a director reeling from a breakup. The reeling in question is not an overtly dramatic one, but rather an internalized feeling conveyed beautifully by actress Qi Xi. With sure-handed tranquility, Song Fang shows that reconnecting with the Earth and basking in natural landscapes is sometimes the perfect medicine to mend a broken heart. – Jordan R.

Charter (Amanda Kernell)

Amanda Kernell’s Sami Blood was one of the most underrated films of the 2010s, and her sophomore feature, Charter, doesn’t disappoint. In the film, Alice (Ane Dahl Torp) abducts her own children from their father (who is their legal guardian) to take them on a charter trip to the Canary Islands. It’s a thorny character study that doesn’t shy away from moral grey areas, asking us to empathize with Alice while questioning her choices. – Orla S.

Careless Crime (Shahram Mokri)

Careless Crime is like a Chinese finger trap. The more you try to dissect it, the harder it is to grasp all its pieces. It’s an effort that takes a great amount of patience but is incredibly rewarding, and that’s not just in its structure. Mokri clearly knew someone would make a movie about this event. Instead, he made a movie about its limits and consequences. It balances iconography, truism, and showy direction until each thread differently reflects another. It’s not too often a movie trusts its audience this much, and the result is one of the most meta movies this side of Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s A Moment of Innocence. – Matt C. (full review)

The Cloud in Her Room (Zheng Lu Xinyaun)

The Hangzhou of Zheng Lu Xinyaun’s The Cloud in Her Room is a funereal city, a protean place rife with cranes and construction sites, where new buildings mushroom overnight and craters devour the earth beneath. People do not belong in that 10-million people’s metropolis as much as inhabit a liminal space–transient presences in a city in constant flux. “Anytime I come back it feels more different than before,” says Muzi (Jin Jing) halfway through her homecoming. A 22-year-old back in town for the New Year festivities, she saunters through her native turf with the wide-eyed wonder of someone who’s been jettisoned into a foreign planet. – Leonardo G. (full review)

The Disciple (Chaitanya Tamhane)

If Nuri Bilge Ceylan can follow a career culminating Palme d’Or win with a film about delusions of adequacy surely anyone can. Not least Chaitanya Tamhane, who was just 27 when Court, his debut, became the talk of the Venice film festival. Like Ceylan’s Pear Tree, Tamhane’s follow-up gave us an ode to the also-ran: a fascinating and humanistic look at the life of a striving musician of Indian traditional music, The Disciple cut close to the bone while offering outside viewers a window onto a dynamic yet still insulated artistic scene. Alfonso Cuarón produced. Awards were won. One shouldn’t have to wait much longer for distribution news. – Rory O. (full review)

Fauna (Nicolás Pereda)

Early in Mexican-Canadian filmmaker Nicolás Pereda’s succinctly effective farce Fauna, Paco (Francisco Barreiro), a thespian with a non-speaking part in the popular show Narcos, is asked to conjure up a performance in the middle of an empty pool hall. His girlfriend’s father wants to see him act on command. Adding to the film’s meta undertones that later turn more noticeable is the fact that Barreirois is in fact part of the Netflix series. – Carlos A. (full review)

Freeland (Kate McLean and Mario Furloni)

After having its premiere postponed at SXSW, rather than let their timely drama sit out the year, the Freeland team instead launched their film with a different kind of wide release strategy, screening at and supporting regional film festivals throughout the country as they offered their communities new films in drive-in and virtual settings. Directed by Kate McLean and Mario Furloni, Freeland is a timely exploration of marijuana’s evolution from the hippy community to Cannibusiness. Starring the brilliant Krisha Fairchild as an aging hippy trying to transition her commune to a legal grow operation in the face of well-funded competition, Freeland is a moving and hauntingly beautiful picture that, I for one, would love to see on the big screen when possible. With a multigenerational appeal (and perhaps some CBD-infused options for dine-in theaters), Freeland might just be an indie cross-over hit. – John F.

Gamak Ghar (Achal Mishra)

Traditions don’t disappear overnight. They slip away slowly over decades, as elders die off and younger generations experience shifts in priority, social norms, and cultural pride. Few films have been able to capture this kind of ebb and flow like Achal Mishra’s Gamak Ghar, a quietly beautiful drama primarily set in the rural compound where one Indian clan gathers for major life events. Split into three separate chapters that take place years apart, the film shows a graceful appreciation for the small decisions and compromises that eventually add up to profound change inside a family dynamic. – Glenn H. (full review)

Genus Pan (Lav Diaz)

With his latest feature Genus Pan, the king of slow cinema Lav Diaz proves that even his fleet-footed efforts can be an unrelenting experience. Clocking in at a smooth 157 minutes, this blistering allegory takes place almost entirely on the ghostly terrain of Hugaw Island. The poverty-stricken Filipino enclave is populated with superstitious citizens who often confront the misery and unfairness of modern life by embracing legends and mythologies of old. – Glenn H. (full review)

Her Socialist Smile (John Gianvito)

You may have known that Helen Keller was a comrade, a life-long socialist and member of the Industrial Workers of the World; in Her Socialist Smile, John Gianvito assembles Keller’s political addresses and writings into a portrait of a warrior for social justice and a passionate, insightful proselytizer of Marxist thought. She instigated a Braille translation of Bakunin and advocated for a general strike during the first Red Scare. Now, in a time of national self-criticism, when seemingly no American monument is safe from revisionism, Helen Keller emerges from Her Socialist Smile to appear even more inspiring, relevant, and righteous than in the official narrative—appears, perhaps, the only truly based person they teach you about in elementary school. – Mark A. (full review)

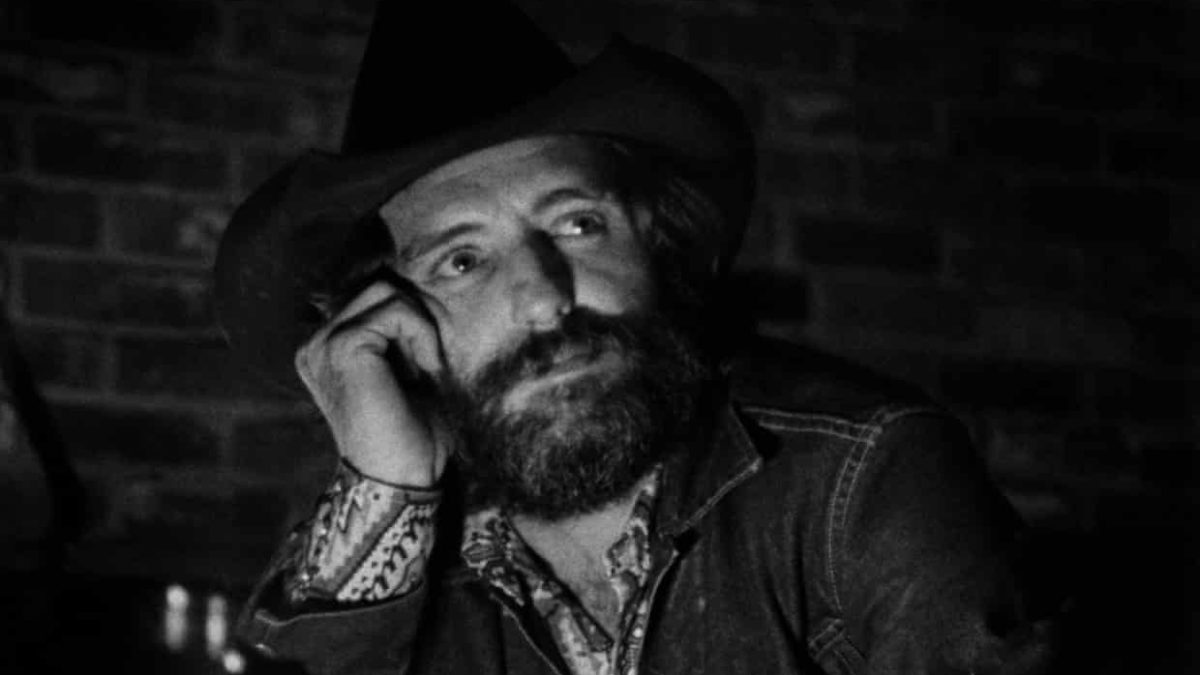

Hopper/Welles (Orson Welles)

Wanting word from—which of course means word with—the next generation, a certified, maybe-sort-of washed-up legend enlisted a legend-to-be whose own legacy would prove equal-parts genius, equal-parts burn-out. We could say Hopper/Welles is lightning-in-a-bottle history, though that’s maybe affording too much credit; one’s liable to appreciate this two-hour dialogue as an intellectual game of cat-and-mouse, a constant attempt at outfoxing and play-acting, or maybe just a dick-measuring contest. But what big dicks these two have! Looking and moving like The Other Side of the Wind‘s better bits—sans that movie’s pressure to fulfill some long-impossible cinephile dream; make what you will of Welles occasionally playing an iteration of John Huston’s Jake Hannaford, because this movie isn’t trying to clarify—it chooses the form of half-remembered dream over rigid document. What better way to continue (if not necessarily close) American cinema’s greatest legacy? – Nick N.

Labyrinth of Cinema (Nobuhiko Obayashi)

No film I saw in 2020 registered as timely and uplifting like Nobuhiko Obayashi’s farewell opus, Labyrinth of Cinema. With all due respect to Mank, if there is one true “love letter to the movies” 2020 gifted us, this is it. Contagiously optimistic and resolutely pacifist, Labyrinth’s requiem for movie theatre doubles as a journey into the horrors of Japan’s 20th century and the films that portrayed them. Whether or not cinema will ever yield Obayashi’s utopia, here’s a film that celebrates the medium in its noblest, most humanist form: a vehicle for compassion. – Leonardo G.

The Last City (Heinz Emigholz)

Following his return to dialogue and performance-driven experimental works with 2017’s Streetscapes [Dialogue], Heinz Emigholz’s The Last City is a delirious, riotous, and harrowing criss-crossing of narratives, tracking a series of conversations on wildly different, frequently taboo subjects––war crimes, incest, drugs––across five different metropolises and a host of ever-shifting characters and incongrously cast actors. Using trademark extreme canted angles and traversal of architecture and space, the film finds unity in its gleeful disunity. – Ryan S.

Last and First Men (Jóhann Jóhannsson)

If any film composer of the last decade defined the period best, it might’ve been Jóhann Jóhannsson, whose synthy, epic tones captured the turbulent, globalized environment of the new century. His work with Denis Villeneuve (Prisoners, Sicario) turned him into a Hollywood name, but the Icelandic instrumentalist was also a musician in his own right who toured the world and released his own records. I’m writing in the past tense, of course, because Jóhannsson died in 2018, though not before he completed his final work, an installation with orchestra combining film and music–with narration by Tilda Swinton–from where this extraordinary cinematic odyssey emerges in its apparently intended final form. Its vision of an apocalyptic extinction inevitably garners interpretations as something of an epitaph to his life and career. – Ed F. (full review)

Limbo (Ben Sharrock)

For years, British right wing newspapers and bigoted politicians have built their platforms on campaigning against asylum seekers, attacking those who are just looking for a new home for their families. The often heartbreaking realities of being an asylum seeker are perfectly depicted in Limbo. While it does capture the processes of a broken system and the bigotry they face brilliantly, the real heart is found in the connections between these men, desperate to return home but burdened with the knowledge that there’s no future there anymore. – Logan K.

Malmkrog (Cristi Puiu)

In Malmkrog, a group of Russian aristocrats gather in a grand rural estate to wax philosophical during a long and luxurious dinner party. The film offers seemingly the closest thing to a direct screen staging of Russian philosopher Vladimir Solovyov’s War and Christianity: The Three Conversations. At 200 minutes, it runs just a few breaths short of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey but seldom ever leaves the confines of the decadent surrounding–indeed, the majority takes place in just three rooms. – Rory O. (full review)

The Metamorphosis of Birds (Catarina Vasconcelos)

The most purely, incandescently beautiful movie of the year is a dreamy cross between documentary and fiction that explores the tricky matter of one’s own lineage. As in a daze, we see three generations of love and sorrow reincarnated in a kaleidoscope of spellbinding images, beneath which there’s longing, blame, and above all a sense of genuine revelation. Families are messy and closure is a myth, but with storytelling this vitally expressive, one may actually hope to heal and some day understand. – Zhuo-Ning Su

Model (Ran Jing)

Director Ran Jing’s debut feature Model focuses on Lu Shi (Yuxian Shang), a Chinese immigrant trying to avoid deportation. Trained as an architect, she washes dishes in a New York City restaurant, hides from a landlord trying to evict her, and is too ashamed to admit her plight to her family back in China. It’s a familiar premise, but Ran fills it with deeply personal moments that document the indignities immigrants face. The movie also shows the personal cost of unrealistic dreams. Lu Shi fails as daughter, mother, and lover, her world crashing around her despite efforts and schemes that would succeed in other plots. Model is a small, very low-budget production that has screened at Asian-American festivals. Ran’s patience, her ability to burrow into domestic scenes, and her willingness to accept her characters’ faults help make this an unusually satisfying movie. – Daniel E.

The Monopoly of Violence (David Dufresne)

Stark and unrelenting, David Dufresne’s The Monopoly of Violence uses the yellow vest movement in France to deconstruct the ways that Western governments use power to maintain control. Dufresne structures by cross cutting between two distinct modes: found footage of police brutality, and one-on-one discussions between various talking heads (lawyers, academics, politicians, and victims of the violence seen in the tapes). Through this construction the visceral impact of the footage gives way to something more analytical, and the film helps reframe the context in which we view the role of institutions of power in our society. It may be an overused term with documentaries, but the universality of Dufresne’s themes combined with his efficiency as a filmmaker makes The Monopoly of Violence essential viewing. – C.J. P.

The Mountains Are a Dream That Call to Me (Cedric Cheung-Lau)

If a mountain-climbing adventure like Everest or Vertical Limit removed its bombastic thrill-seeking setpieces and was instead directed with the patient, reverent eye of Apichatpong Weerasethakul one may conjure up something like The Mountains Are a Dream That Call to Me. Cedric Cheung-Lau, who established his career on the lighting teams of A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, The Mend, Little Men, and more notable indies, makes his feature directorial debut with this peaceful, meditative journey through the Annapurna Mountain range in Nepal. Compact in narrative scale, but as epic as one can imagine in terms of capturing the awe of the gorgeous environment our small set of characters traverse, the film is a meditative testament to appreciating one’s surroundings in all their glory. – Jordan R. (full review)

Nasir (Arun Karthick)

Here’s a film for which the label “low-key” feels particularly misleading, one whose power resides in its simplicity, in its ability to conjure grace out of a beguilingly ordinary tale. Nasir, Indian writer-director Arun Karthick’s sophomore feature, is a film of quiet pleasures and unassuming wonders. It follows a day in the life of the salesman it is named after, and unspools at his becalmed and contemplative pace. It opens with the sound of a morning prayer and retains that early morning dream-like aura, locking you in a state of reverie and then shattering it in a finale of startling violence. – Leonardo G. (full review)

No Ordinary Man (Aisling Chin-Yee and Chase Joynt)

With No Ordinary Man, directors Chase Joynt and Aisling Chin-yee reclaim the lost history of trans jazz musician Billy Tipton. Because no moving footage of Tipton exists, in this documentary, Joynt and Chin-yee ask transmasculine actors to “audition” to play Tipton, discussing their interpretations of his life and how they’d play him. Through this device, the filmmakers connect how trans history impacts trans people now. – Orla S.

Pacified (Paxton Winters)

Part coming-of-age drama, part revenge thriller, Pacified takes place in Rio’s Prazeres favela around the 2016 Olympics. Writer and director Paxton Winters lived in Prazeres for three years before assembling a cast and crew, including Bukassa Kabengele as an ex-con and newcomer Cassia Nascimento Gil as the twelve-year-old Tati. Their relationship drives a story that probes into the beauty and violence of the favelas. Winters is clear-eyed about what it takes to survive in Prazeres, but his film avoids the moralism of artists who helicopter in to offer opinions about poverty and injustice. With residents working on the crew and in many supporting roles, Pacified feels authentic and, more important, accepted by the people it portrays. Pacified won awards at several film festivals, including both Best Debut Cinematography (Laura Merians) and Best Debut Director (Winters) at Camerimage. But even with Darren Aronofsky as producer, the film fell victim to both the pandemic and to Disney’s purchase of Fox Searchlight. Winters is currently shooting Outside the Wire, set in the Iraq War. – Daniel E.

Quo Vadis, Aida? (Jasmila Žbanić)

The most moving, harrowing, and best film I saw at TIFF ‘20 was Jasmila Žbanić’s Quo Vadis, Aida?. The film reenacts the horrific Bosnian genocide through the eyes of a UN translator stuck between the powerful officials calling the shots and the vulnerable townspeople to whom she belongs. It’s a fascinating study of power and complicity that never glorifies violence, instead training an accusing lens on those who hold the power to hurt others. – Orla S.

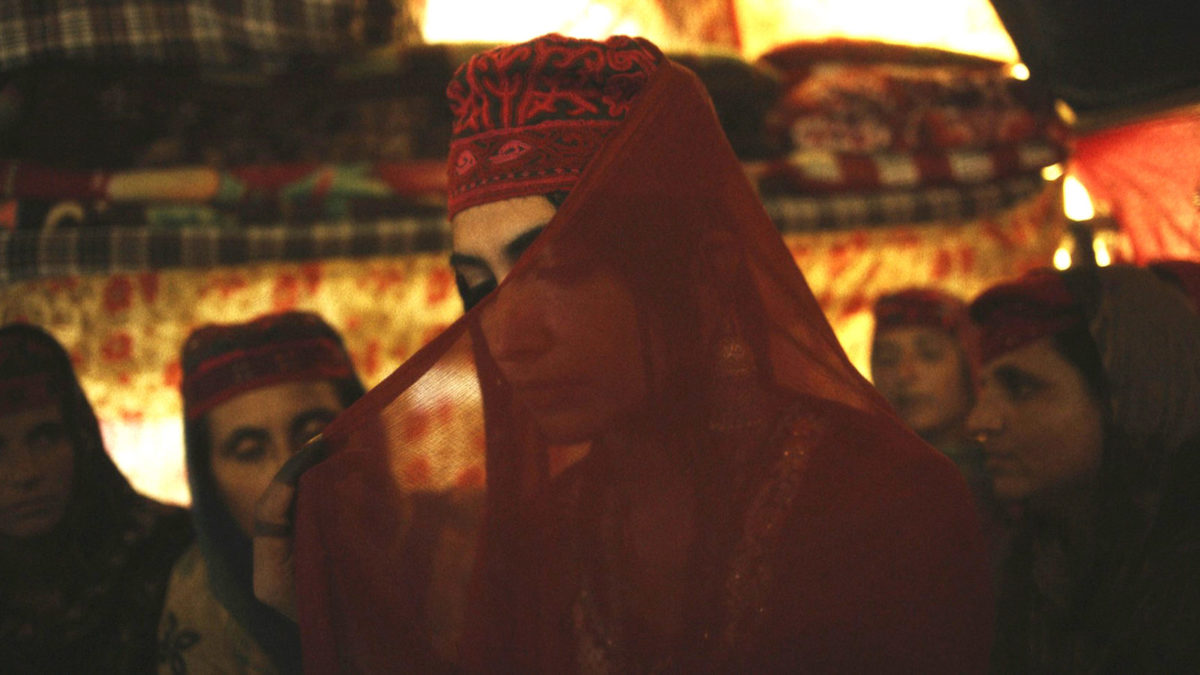

The Shepherdess and the Seven Songs (Pushpendra Singh)

Northwest India’s Jammu and Kashmir region resides at the center of a longstanding geopolitical stalemate involving neighboring Pakistan. While those tensions are referenced in The Shepherdess and the Seven Songs, they are not the film’s focal point. Instead, paranoia and opportunism have become fully ingrained in the forest area’s mountainous bedrock. Of more importance is why these characters either accept or subvert such societal realities, and how they normalize modes of corruption and gender inequality under the guise of tradition or progress. – Glenn H. (full review)

Siberia (Abel Ferrara)

Abel Ferrara: habitué of end-of-year undistributed lists, impossibly pure artistic spirit – perhaps these two factors aren’t irrelevant to one another. Good work finds a way, and his output maybe benefits from staggered release patterns––the films linger and grow in the mind, built to last beyond more superficial art. I had no initial doubts, however, about the quality and maturity present in Siberia, a confessional dreamscape set in what Cybotron’s famous Detroit techno track calls the ‘alleys of the mind,’ featuring his muse Willem Dafoe in consummate form. Rarely has self-portraiture (the film is greatly concerned with Ferrara’s journey to sobriety) felt so immediate, and anything but self-indulgent. – David K.

Sweat (Magnus von Horn)

Sweat is one of the best films about an influencer that has been made to date. While other films about social media dismiss their characters as vapid, Magnus von Horn’s latest has so much empathy for fitness influencer Sylwia (Magdalena Kolesnik). Von Horn places blame on the mechanisms of social media for Sylwia’s sadness. It’s a film that peels back the masks we wear online and questions whether we ever stop performing for our followers. – Orla S.

Sweet Thing (Alexandre Rockwell)

Shot in a beautiful monochromatic black and white, indie veteran Alexandre Rockwell’s Sweet Thing premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival but has yet to be distributed. Casting his kids Nico and Lana in the lead roles––who are both great––their characters are forced to keep it together while the adults in their life begin to crumble under bad habits. Most of the people appearing in the film are non-actors except for Will Patton and Rockwell’s wife Parsons, but never does that hinder a scene from believability. It’s a harrowing but hopeful tale and one that, if it spent too much time in the mud, could’ve been depressing. – Erik N.

Tahara (Olivia Peace)

The word tumah in Jewish law is the state of being impure—ritually and morally. And it seems there are many reasons why you might fall under this category as stated in the Torah’s Book of Leviticus. Touch a corpse: impure. Touch something that already touched a corpse? Impure. Touch the decaying flesh of dead animals? Impure. Give birth? Impure: but only for seven (son) and fourteen days (daughter) depending on the baby’s gender. Have an “unnatural” discharge from your genitals (including menstruation)? Yes. You guessed it. Impure. And that’s bad. Nobody wants to be impure. Look at Christians. We’ll say anything on our deathbed for absolution (purity). But today’s youth isn’t dying (wars, famine, etc. notwithstanding). To the living of any faith, purity can always come later. Except, of course, when it can’t. Just ask anyone at the high school synagogue for young Samantha’s funeral. – Jared M. (full review)

There are not thirty-six ways of showing a man getting on a horse. (Nicolás Zukerfeld)

As wonderfully absurd as its title might suggest, Nicolás Zukerfeld’s There are not thirty-six ways of showing a man getting on a horse. is a two-pronged feature-length video essay, serving as first a catalogue of motion and shared narratives across Raoul Walsh’s oeuvre, then as an eminently comedic yarn tracing the development of movie myths and the ineffable connections within cinephilia. The film is borne from love, and its wit and humor shine even brighter. – Ryan S.

This is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese)

When observing global cultural differences, some of the most telling points of distinction are seen in how different societies treat death. Beyond this, the ongoing 2020 pandemic has resensitized us, especially in the west, to an earlier way of life not seen since the two world wars and the emergence of modern medicine, where the specter of death looms larger. A certain mode of arthouse film is well-equipped to process these ideas. The deeply referential new South African film This is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection strongly evokes Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry, perhaps cinema’s greatest contemplation of the subject. – David K. (full review)

The Trouble With Being Born (Sandra Wollner)

Sandra Wollner’s The Trouble with Being Born was no stranger to controversy this year, having been pulled from the Melbourne International Film Festival after concerns over the film’s subject matter. It’s a bit surprising and disappointing to see films still fall victim to this sort of censorship. Wollner’s film is only disturbing in what it brings up rather than what it shows, taking place in the near future where a man lives with an android taking the form of a young girl (you can probably guess where this is going). Rather than going for cheap provocation, Wollner uses a distanced, unsettling style to emphasize the implied and human dangers of technology, and how it can expose and accommodate some of the worst aspects of humanity. Distributors have been understandably hesitant to approach this film, but The Trouble with Being Born is smart and upsetting in equal measure, and bound to stick with anyone who watches it. – C.J. P.

Waikiki (Christopher Kahunahana)

Offering a literal behind-the-scenes glimpse of the iconic tourist spot, Christopher Kahunahana’s splendid debut feature, Waikiki, is a succinct emotional dive into the complex intergenerational trauma that plagues many Native Hawaiians. Foregrounding the stark economic divide between the resorts and the city, Kahunahana’s film is purportedly the first film written and directed by a Native Hawaiian. A marvel of economic storytelling, Waikiki spotlights the social and spiritual erosion of colonial tourism on the indigenous population. – Christian G. (full review)

Wildfire (Cathy Brady)

Staring Nora-Jane Noone and the late Nika McGuigan as estranged sisters reconnecting in their Northern Ireland hometown, Cathy Brady’s knockout feature debut Wildfire was one of the gems at TIFF’s Discovery section that deserves wider attention. When Kelly (McGuigan) returns from traveling abroad to the doorstep of her sister Lauren (Noone), sparks fly as we explore both personal and regional traumas in a region marked by terrorism. The past “troubles” for which they are slightly too young to have been able to participate in any “truth and reconciliation” for come to an almost musical confrontation that’s one of the most unforgettable sequences I’ve seen this year. Brady’s powerful picture is a remarkable study on how the baggage of one’s hometown can affect their future, a riveting character study that deserves to be seen. – John F.

Honorable Mentions

All the Dead Ones

Beans

Days of Cannibalism

Enemies of the State

Frank & Zed

Funny Face

Giraffe

Inconvenient Indian

Kala azar

Like a House on Fire

The Obituary of Tunde Johnson

Ouvertures

The Plastic House

Servants

Stray

The Television Event

Time of Moulting

The Whaler Boy