Looking for what to see in theaters? Our feature, updated weekly, highlights our top recommendations for films currently in theaters, from new releases to restorations receiving a proper theatrical run.

While we already provide extensive monthly new-release recommendations and weekly streaming recommendations, as distributors’ roll-outs can vary, this is a one-stop list to share the essential films that may be on a screen near you.

Anora (Sean Baker)

Sean Baker’s radiant rom-com / rollicking thriller Anora is one of the most acclaimed films of the year for good reason. The Palme d’Or winner is finally now in theaters, giving audiences a chance to witness Mikey Madison’s captivating performance. Luke Hicks said in his review, “Anora is a devastating, gut-busting beauty––regular cinematographer Drew Daniels lending his brilliance to yet another Baker triumph––the kind that hurts your heart and holds you tight to recover at the same time, tears of laughter streaming down your face.”

Between the Temples (Nathan Silver)

In a state of arrested development after his wife unexpectedly died from a freak accident, Ben Gottlieb (Jason Schwartzman) is suicidal, pleading to a truck to just run him over and begging that he be fired from his job as cantor at the local Jewish temple in upstate New York. While this set-up may not scream comedy, Between the Temples is in fact hilarious, packed with endless jokes and adoration for physical gags while we witness Ben find new meaning in life through an unexpected acquaintance. Above all, Nathan Silver’s feature, from a script he co-wrote with C. Mason Wells,is a thrillingly alive, nimble piece of filmmaking: shot on 16mm by Sean Price Williams with faces of its ensemble guiding every movement, and edited by John Magary with a frenetic yet defined rhythm, Between the Temples is a witty, biting portrait of finding one’s footing in both faith and friendship. – Jordan R. (full review)

Close Your Eyes (Víctor Erice)

Curious, self-referential, and rich, Close Your Eyes has had a difficult passageway into the world, with its Cannes world premiere dogged by reports of conflicts over its runtime, its non-competition placement, and Erice’s own in-person boycott of the screening. Its final form also is a scarcely believable one, singular and self-possessed even amidst all the latter-day auteur work that’s screened in recent days: although it’s studded with other media, such as an unfinished film of Garay’s and trashy Spanish primetime TV, the main bulk is a pokily shot mystery “procedural,” told mainly in one-to-one dialogue scenes, shot in judicious singles with minimal coverage and muted lighting. But Erice is gradually able to accrete a rich character study of Garay and, yes, another meditation on the Grand Power of Cinema––not that we’re lacking in those at the moment––enriched by the fact that this theme, together with memory and longing, has long been the director’s modus operandi. – David K. (full review)

A Different Man (Aaron Schimberg)

Sebastian Stan’s best performance thus far is finally arriving some eight months after its Sundance debut. Jake Kring-Schreifels said in his review, “There are a lot of ways A Different Man could go and a lot of things it could be. Aaron Schimberg’s uniquely uncomfortable, uncomfortably unique feature sometimes plays as a reverse-Frankenstein medical horror, a tragic life-imitates-art satire, and a spiraling relationship drama. To its ambitious and distinct credit, it attempts packaging them all into ominous-sounding harmony, as if Charlie Kauffman’s surrealist Escher concoctions became a Twilight Zone episode modeled after David Lynch’s Elephant Man or Beauty and the Beast. It’s a dark, hilarious, and deeply unsettling portrait of a disfigured man that’s also an unflinching mirror of a looks-focused industry.”

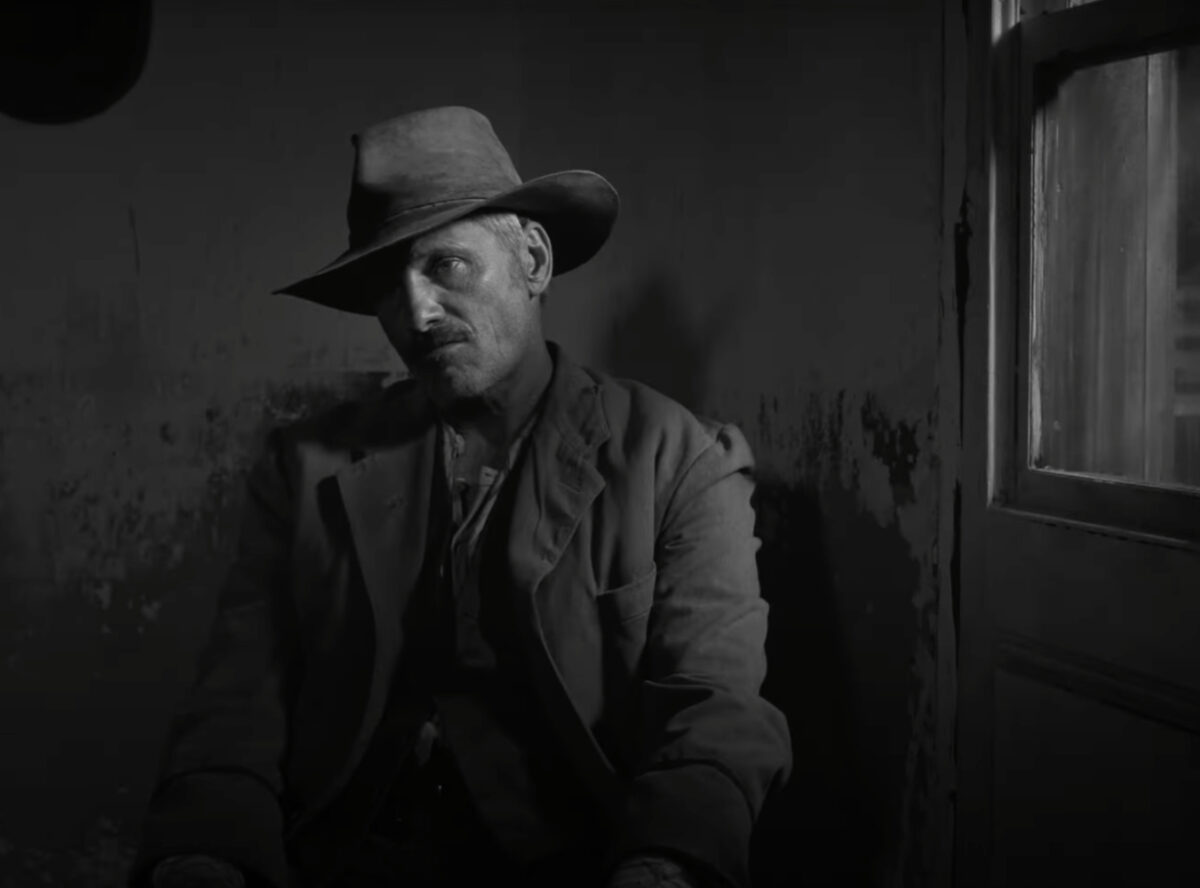

Eureka (Lisandro Alonso)

One of the most-anticipated films to premiere at Cannes last year was Lisandro Alonso’s Jauja follow-up Eureka. An epic spanning three different stories across space and time, with a cast including Viggo Mortensen and Chiara Mastroianni, the Argentine director’s most ambitious work yet is now finally in theaters. Leonardo Goi said in his Cannes review, “Nine years since that underground epiphany, along comes Eureka, a film that, for large chunks, seems to emerge from the same hallucinatory terrain Jauja opened up. Like all its predecessors, this unfurls as a literal journey dotted with solitary wanderers either searching for or mourning lost relatives. (“All families disappear eventually,” Gunnar was told down the cave, a line that might as well double as the director’s motto.) Old tropes and motifs notwithstanding, Alonso’s latest is his most ambitious: a tripartite film, Eureka sides not with the white strangers in strange lands that had long peopled Alonso’s oeuvre, but with the native communities facing these invaders. Its scope is ecumenical, its geography massive. In barest terms, Eureka’s designed to sponge something of, and locate parallels between, the experience of Indigenous communities stranded in three markedly different milieus: the Old West; South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Reservation in the present day; and finally the jungles of early-70s Brazil.”

Good One (India Donaldson)

It’s been nearly two decades since Kelly Reichardt’s Old Joy showed how the wilderness can be an open canvas to explore the breaking points of male friendship and reckoning with a midlife crisis. While those emotional quandaries are evergreen, it’s appropriate timing to bring an entirely new element to this conceit. India Donaldson’s carefully observed, refreshingly patient, beautifully rendered debut feature Good One shifts the perspective, concerning a 17-year-old girl who embarks on a camping trip in the Catskills with her father and his best friend. Through an accumulation of minute details and uneasy glances, the drama becomes a portrait of increasingly crossed boundaries leading to an ultimate breaking point. – Jordan R. (full review)

Matt and Mara (Kazik Radwanski)

A standout at the 2024 Berlinale, Canadian director Kazik Radwanski’s Matt and Mara reunited him with his Anne at 13,000 ft star Deragh Campbell, joined by Matt Johnson, director of BlackBerry. Savina Petkova said her Berlinale review, “Radwanski hones his intuitive directorial skills into crafting a narrative out of these paradoxes of intimacy that bind the two. What grounds the abstraction is the chemistry Campbell and Johnson share, and the safety they are both equally unwilling to abandon. Matt acts, Mara reacts; to a certain extent, he “activates” her in a way her roles of a tutor, wife, and mother cannot. In a string of minor events highlighting their compatibility and clashes, it becomes less about the “will-they-won’t-they” than about exploring the boundaries of oneself in a controlled environment. Not exactly an experiment, but certainly a testing ground.”

Megalopolis (Francis Ford Coppola)

If you dove head first into Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis, you would get a concussion. The filmmaker’s supposed opus––a glitzy, gargantuan, long-gestating project that he conceived of in the late ‘70s, attempted to make more than once in the ‘80s, rewrote countless times over the last four decades, and eventually self-financed for $120 million due to lack of external support––has had cinephiles like myself drooling over its scope and potential for years. Alas, there is no deep end in this pool. Don’t let that deter you though. Receive it with a healthy dose of doubt and let it reshape (and perhaps healthily lower) your expectations. Because, at the end of the day, for better and for worse, in awe and in tired confusion, Megalopolis is a garish wonder to behold. – Luke H. (full review)

The Outrun (Nora Fingscheidt)

After a relatively quiet few years, Saoirse Ronan is returning in a major way this fall, leading two new features: Nora Fingscheidt’s Sundance highlight The Outrun and Steve McQueen’s Blitz. The former is set for a release from Sony Pictures Classics this week. Dan Mecca said in his review, “Maybe the smartest decision made in The Outrun, directed by Nora Fingscheidt, is its fractured narrative device. Based on the 2016 memoir of the same name by Amy Liptrot (co-writing with Fingscheidt), the film offers a frank, unwavering look at addiction with the great Saoirse Ronan (who also produces) in the lead role. We move forward and backward in time, often relieved to be clear from horrible sins of the past only to be thrust back into them minutes later. In this way, the picture reflects its subject with painful precision.”

Rumours (Guy Maddin, Evan Johnson, and Galen Johnson)

While Guy Maddin and Evan & Galen Johnson’s latest endeavor brings the most star power they’ve had in a film thus far (Cate Blanchett and Alicia Vikander among them), Rumours loses none of the trio’s singular sense of humor. Following political leaders who become stranded as the apocalypse may be underway, it’s a wacky yet grounded look at the crumbling veneer of power and influence when there’s no one left to lead. Luke Hicks said in his review, “If you do know the longtime Canadian experimentalist’s filmography, then you know nothing seems less likely than Rumours, his grand, Cannes competition-grade entrance into (supposedly) normcore feature filmmaking which, when discussing Maddin, encompasses everything inside and most things outside Schrader’s Tarkovsky Ring. Even less likely is the idea that Maddin would take on modern, real-world events, the film opening on the press podium of the G7 summit, albeit one led by slightly fictionalized, more blatantly vapid versions of the leaders they represent.”

The Substance (Coralie Fargeat)

Coralie Fargeat made a splash with her debut Revenge. But she was only standing in a puddle, endearing niche corners of the global cinephile community to her cinematic bloodlust for sexually violent men and gore-horror filmmaking. With her second, The Substance, she’s fully submerged in the ocean and making waves. Meet Elisabeth Sparkle, a Demi Moore-esque A-lister (played by Demi Moore) whose stardom has long since faded, leaving her, to great displeasure, in the instructor’s seat of a glam morning-fitness class called “Sparkle Your Life.” We learn about her iconic career through a cleverly designed timelapse that opens the film––a bird’s-eye view of her Hollywood Walk of Fame star being minted, premiered, adorned, celebrated, surrounded, stood on, passed, ignored, and eventually forgotten. – Luke H. (full review)

Union (Brett Story, Stephen Maing)

Amazon Labor Union (ALU) president Chris Smalls is not the star of the documentary Union. He is just one part of the congregation in Brett Story and Stephen Maing’s co-directed film. An early glimpse of Smalls finds him discreetly flipping burgers and hot dogs at a grill. It took an employee to ask Smalls if he’s the ‘low-key famous’ Smalls for the leader to list his media recognitions. He doesn’t want clout for his union organizing, but rather to be known for making laborers heard, enabling a better society for his children and comrades, and proving to white executives that he can manage a flock in his distinguished streetwear outfits. – Edward F. (full review)

More Films Now Playing in Theaters

- The Apprentice

- Daaaaaalí!

- Eno

- Exhibiting Forgiveness

- My Old Ass

- Nocturnes

- We Live in Time

- The Wild Robot

The Best New Restorations Now Playing in Theaters

The below list features newly restored films receiving a theatrical release run. For NYC-specific repertory round-ups, bookmark NYC Weekend Watch.

- The Burmese Harp

- The Devil, Probably

- The Fall

- Paris, Texas

Read all reviews here.