For our most comprehensive year-end feature we’re providing a cumulative look at The Film Stage’s favorite films of 2020. We’ve asked contributors to compile ten-best lists with five honorable mentions—a selection of those personal lists will be shared in the coming days—and after tallying votes, a top 50 has been assembled.

It should be noted that, unlike our other year-end features, we placed no requirement on a selection being a U.S theatrical release, so you may see some repeats from last year and a few we’ll certainly discuss more over the next twelve months. So: without further ado, check out our rundown of 2020 below, our ongoing year-end coverage here (including where to stream many of the below picks), and return in the coming weeks as we look towards 2021.

50. The Metamorphosis of Birds (Catarina Vasconcelos)

The most purely, incandescently beautiful movie of the year is a dreamy cross between documentary and fiction that explores the tricky matter of one’s own lineage. As in a daze, we see three generations of love and sorrow reincarnated in a kaleidoscope of spellbinding images, beneath which there’s longing, blame, and above all a sense of genuine revelation. Families are messy and closure is a myth, but with storytelling this vitally expressive, one may actually hope to heal and some day understand. – Zhuo-Ning Su

49. Days (Tsai Ming-Liang)

“Thank you for the days / those endless days, those sacred days you gave me” So begins the classic 1968 single by the Kinks, and Tsai Ming-Liang has an apposite poster tagline here if he needs it. But altering any one element of this immaculate comeback feature––say, putting this very track against the closing credits––would be heresy, especially when it already contains a beautiful use of diegetic music in the theme from Chaplin’s Limelight. I was lucky enough to see his tender, spellbinding new film at BFI London’s in-person, distanced screenings, and strongly hope others are afforded that pleasure when things open again in 2021––when it will most certainly appear on TFS’s list for the second year running. – David K.

48. The Cordillera of Dreams (Patricio Guzmán)

Having experienced the authoritarian traumas of 20th-century Chile firsthand, documentarian Patricio Guzmán makes films that explore the grieving process at both a personal and national level. His latest masterpiece, the third part of a trilogy that includes Nostalgia for the Light and The Pearl Button, expands this scope to an elemental level. Through the most sublime stylistic means, it positions the Andes mountain range as an organic witness to the reign of terror that has transpired, and a reminder of the enduring hope that lies ahead. – Glenn H.

47. Isadora’s Children (Damien Manivel)

Winner of Best Director at the 2019 Locarno Festival, Damien Manivel’s Isadora’s Children surprises with its sincere take on the healing powers of art and creativity. Manivel focuses on four women linked to a performance piece by dancer Isadora Duncan in four ways: one studies it, one teaches it, one learns it, and one watches it at a recital. Through these four portraits, Isadora’s Children shows how an art piece can travel almost a century through time and space, reach out to people from different walks of life, and offer them something therapeutic. Manivel’s ability to convey how art can capture and transmit the intangible and experiential is something to behold. – C.J. P.

46. The Grand Bizarre (Jodie Mack)

A marvel of economy, rhythm, and, paradoxically, totality, Jodie Mack’s infectious The Grand Bizarre is a globetrotting compendium of textures: visual, aural, material. Draped by Mack’s characteristic IDM-adjacent pop soundtrack and filmed over five years, this frenetic 16mm collage traffics in Mack’s preferred modes of stroboscopic montage and stop-motion––but mounted with the scope and kinetic clarity of an industrial musical. – Michael S.

45. Babyteeth (Shannon Murphy)

No matter how prepared we think we are to confront our own mortality, we aren’t even close. Babyteeth will press some buttons because death doesn’t leave time for taboo or decorum, but anyone who says its characters (Ben Mendelsohn, Essie Davis, and Eliza Scanlen are phenomenal) are wrong in their decision-making is only exposing the privilege of never having gone through a tragic undertaking such as watching a teenage family member slowly die before their eyes. Rules don’t apply to the scenario’s heartbreakingly intrinsic feedback loop as written with authentic nuance by Rita Kalnejais and filmed beyond convention by director Shannon Murphy. Just its immovable yet redemptive truth: we remember our loved ones’ lives, not their deaths. – Jared M.

44. The Whistlers (Corneliu Porumboiu)

Romanian New Waver Corneliu Porumboiu’s latest feature finds him taking yet another unexpected turn, this time in a mainstream direction. A full-blown heist film with multiple perspectives, jumbled timelines, plot twists, and references to filmmakers like John Ford and Alfred Hitchcock, The Whistlers stuffs several movies worth of information in its short runtime. But Porumboiu’s confidence and versatility as a filmmaker makes his plate spinning look easy, creating a blast of pure entertainment that puts more recent studio tentpoles and high concept films like it to shame. – C.J. P.

43. Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (George C. Wolfe)

Ma Rainey is a compact yarn with grand observations. Faith, despair, prosperity and persecution are reconciled in the paradox of an industry (and country) built on black voices, but controlled by white ones. Viola Davis anchors as the obstinate blues icon, who manages to command both on and offscreen. If she is the film’s solid ground, then Chadwick Boseman is pure lightning. He performs as a man seemingly aware of his fate, going for broke in spectacular fashion, as if to expel all that remains of his immense talents in one of the most haunting and generous performances put to film. – Conor O.

42. Collective (Alexander Nanau)

Since many Americans refuse to acknowledge that they weren’t spared from money’s global erosion of honesty and empathy, a film like Alexander Nanau’s Collective becomes a crucially important mirror for them to finally confront it. This documentary forces us to see the victims of two tragedies (a nightclub fire and the unethical institutions tasked to help them) as more than statistics to become a damningly candid treatise on the ills of society and the damage wrought when bad people ascend to power with little interest in the public that put them there. It’s a must-see journey of integrity amidst corruption in pursuit of necessary change, with the harsh realization that things may already be too late. – Jared M.

41. The Disciple (Chaitanya Tamhane)

In life we can’t all be winners––a brutally simple, often painful truth communicated with tenderness and a remarkable lack of cynicism in Tamhane’s exquisite sophomore feature. Embedded in the enchanting world of Indian classical music, it chronicles one man’s attempt at glory and ends up an ode to all of history’s also-rans, their stories unremembered if no less profound. Though looking and sounding heavenly throughout, you won’t find another film this year more firmly rooted in the earthly compassion of humanist cinema. – Zhuo-Ning Su

40. Labyrinth of Cinema (Nobuhiko Obayashi)

No film I saw in 2020 registered as timely and uplifting like Nobuhiko Obayashi’s farewell opus, Labyrinth of Cinema. With all due respect to Mank, if there is one true “love letter to the movies” 2020 gifted us, this is it. Contagiously optimistic and resolutely pacifist, Labyrinth’s requiem for movie theatre doubles as a journey into the horrors of Japan’s 20th century and the films that portrayed them. Whether or not cinema will ever yield Obayashi’s utopia, here’s a film that celebrates the medium in its noblest, most humanist form: a vehicle for compassion. – Leonardo G.

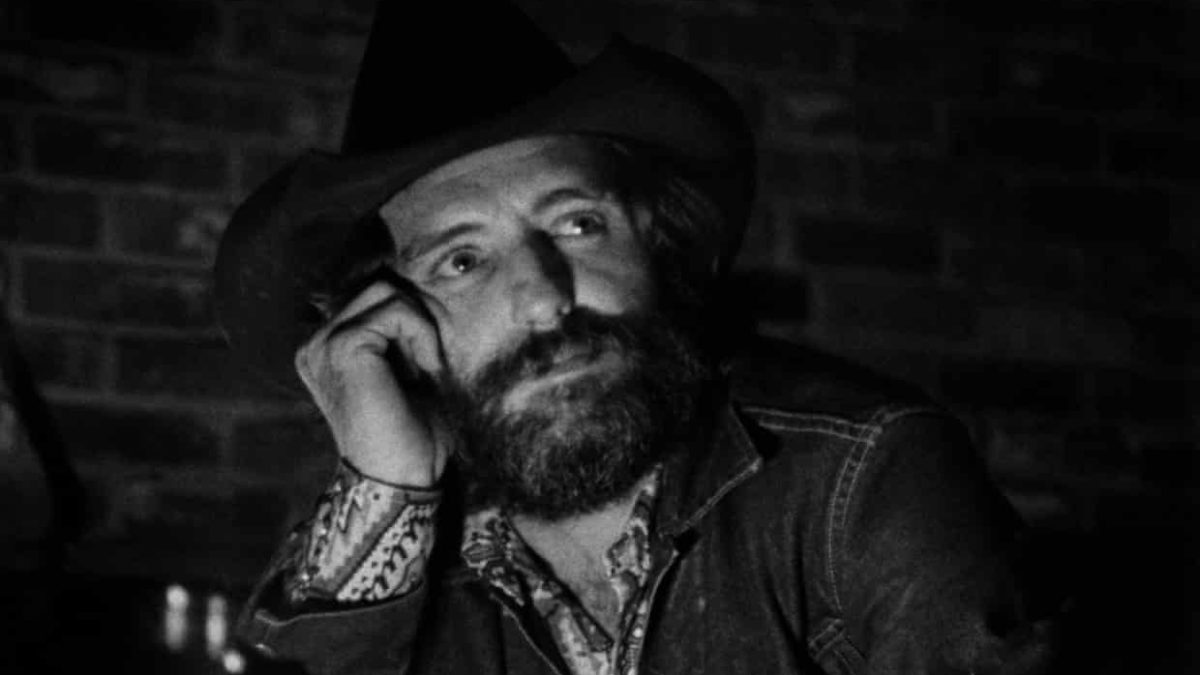

39. Hopper/Welles (Orson Welles)

Wanting word from—which of course means word with—the next generation, a certified, maybe-sort-of washed-up legend enlisted a legend-to-be whose own legacy would prove equal-parts genius, equal-parts burn-out. We could say Hopper/Welles is lightning-in-a-bottle history, though that’s maybe affording too much credit; one’s liable to appreciate this two-hour dialogue as an intellectual game of cat-and-mouse, a constant attempt at outfoxing and play-acting, or maybe just a dick-measuring contest. But what big dicks these two have! Looking and moving like The Other Side of the Wind‘s better bits—sans that movie’s pressure to fulfill some long-impossible cinephile dream; make what you will of Welles occasionally playing an iteration of John Huston’s Jake Hannaford, because this movie isn’t trying to clarify—it chooses the form of half-remembered dream over rigid document. What better way to continue (if not necessarily close) American cinema’s greatest legacy? – Nick N.

38. World of Tomorrow Episode Three: The Absent Destinations of David Prime (Don Hertzfeldt)

With such a guiding principle, it is no wonder that in the last five years Hertzfeldt has crafted what might be the crowning achievement of modern science fiction. Each chapter of his trilogy—which one can only hope will someday outgrow that designation—only grows in scope and scale and ambition, and it’s to Hertzfeldt’s credit as a writer and director that the additional time and spectacle never feels excessive or indulgent. Rather, his canvas and palette seem to grow parallel to his expanding thesis. As such, when one learns that Episode 3 is longer than the two that came before, they can be assured that it is also more aesthetically inventive and narratively complex. – Brian R.

37. Education (Steve McQueen)

Each of the five full-length films in Steve McQueen’s Small Axe is, in its own way, extraordinary. Education hits hardest. It is startling to see a film about a young person so believable, so harrowing, and so true—perhaps not since François Truffaut has a filmmaker exhibited such deft understanding of youth. Throughout Small Axe, McQueen explores the pungent, lingering effects of institutional racism with radical, fearless filmmaking, and Education is especially a triumph. – Chris S.

36. La Llorona (Jayro Bustamante)

As a proud Central American, I continue being in awe of Jayro Bustamante’s output and the way he’s almost single-handedly positioning one of the poorest regions of the world as a cinematic force to be reckoned with. The tale he tells in La Llorona might be endemic to Guatemala, but through his subversive use of the horror genre, Bustamante delivers a film for the ages. He reminds us that the ghosts that live longest are those of the innocent who continue perishing to greed and corruption. – Jose S.

35. Proxima (Alice Winocour)

Alice Winocour hasn’t earned the same attention as her La Fémis peer, Céline Sciamma, despite the fact that they share an editor and sound editor. But with three rich and varied features under her belt—Augustine, Disorder, and Proxima—it’s time for Winocour to enter the stratosphere. She should have done with Proxima, a film that uses the grand arena of space to explore an intimate mother-daughter relationship. It’s stunningly well crafted, exquisitely emotional, and features one of Eva Green’s best performances, playing an astronaut preparing to leave her daughter behind for a year-long space mission. – Orla S.

34. A Sun (Chung Mong-hong)

Chung Moog-hong’s A Sun––a rich Taiwanese drama with the texture of a novel––was unceremoniously released on Netflix in the middle of the Sundance Film Festival, and one of the year’s best pictures might have been overlooked if not for a few critics that praised it during its run at TIFF. The film follows a family of four rocked by their young son A-Ho’s (Greg Hsu) crime and their oldest son A-he’s (Wu Chien-ho) suicide. Examining the grieving process of parents Qin (Samantha Ko) and A-wen (Chen Yi-wen) as they let one on the wrong path go, only to mourn another, A Sun is a stylishly directed family crime drama that unfolds in surprising and profound ways. As each member tries to make amends with each other, we witness a seedy criminal underworld that exists beyond the glimmer of luxury. – John F.

33. Tesla (Michael Almereyda)

Every few years there’s a biopic to truly upend our notion of genre boundaries. The always inventive Michael Almereyda doesn’t just break conventions with Tesla––he wholly flips the script. Led by Ethan Hawke in one of this year’s best performances, the entertaining anachronisms, playful fabrications, and even an unexpected musical performance feel like they get more to the heart and spirit of Nikola Tesla than any by-the-books biopic could hope to achieve. – Jordan R.

32. The Way Back (Gavin O’Connor)

Given the “victory heals all” ethos of most sports movies, one could be forgiven for thinking that The Way Back would be just another handsome, effecting, but not revolutionary entry into that genre. And if that were its only goal, Gavin O’Connor’s rousing underdog tale might still be among the best of the year. However, anchored by a stunning lead performance by Ben Affleck, the script by Brad Ingelsby actually derives a much deeper understanding of pain and addiction, making this a movie that delivers not only rousing athletic stakes but also deep pathos. – Brian R.

31. Beginning (Dea Kulumbegashvili)

Georgian filmmaker Déa Kulumbegashvili’s debut Beginning rests in the stares and prolonged silences of Jana (Ia Sukhitashvili), a wife and mother entrenched in a tiny Jehovah’s Witness community. With little dialogue and a square aspect ratio, the film becomes a haunting tale of seclusion, repression, and breaking free of religious, gender, and traditional constraints. Danger lurks off-screen as Jana navigates a lonely existence, attempting to find control in horrific situations. Beginning is an auspicious debut and worthy, difficult meditation. – Michael F.

30. Black Bear (Lawrence Michael Levine)

Bifurcated into two distinct stories, Lawrence Michael Levine’s Black Bear is not only a showcase of Aubrey Plaza’s expressive range, which was always teased in previous projects, but a treatise on independent filmmaking and the relationship between life and art. Plaza, alongside Christopher Abbott and Sarah Gadon, moves into different roles as the movie switches from relationship drama to behind-the-scenes look at filmmaking, and Levine asks his audience to draw connections themselves, never fully explaining how these disparate narratives link (or even what the literal Black Bear symbolizes). As we grapple with the possibilities of film sans theaters, Levine’s project proves a riddle, demanding debate and conversation. – Christian G.

29. The Vast of Night (Andrew Patterson)

Andrew Patterson’s micro-budgeted debut is full of the bravado one might expect from a first-time filmmaker, but what sets The Vast of Night apart is how its director has the wits to elevate his film above mere style. Taking his time to establish a (sparse) setting and develop his characters, Patterson lets loose when the narrative kicks into high gear, pulling from a bag of tricks and influences ranging from radio plays to The Twilight Zone and early Spielberg. Rather than use the past for nostalgia highs or mining its aesthetics, The Vast of Night engages with it to capture a sense of mystery and wonder from the era that other films can only chase after. – C.J. P.

28. Mangrove (Steve McQueen)

A devastatingly powerful courtroom drama from Steve McQueen, and his lengthiest entry in the Small Axe anthology. The calm but heated logic in which Shaun Parkes attempts to understand why the police hate him, why the country hates him, and the lengths to which the systems of governing rage against his people—who only want to enjoy themselves within the community at the Mangrove restaurant—is saddening and infuriating. What may feel like a message movie about racism is an unfortunate, clear-eyed tragedy—even by the end, when there seems to be victory, circumstances do not improve. – Erik N.

27. I Was at Home, But… (Angela Schanelec)

Following her belated international breakthrough, Angela Schanelec brought her near-abstract, mysterious approach to a more piercingly emotional story. I Was at Home, But… is nominally about the rhythms in a life where grief is always a dull ache, but it incorporates much more into its free-floating orbit: the representation of suffering, the individual resonances of art, and above all the problems of communication. Its compositional precision only accentuates an essential tentativeness, a need to keep moving forward without looking back. – Ryan S.

26. Fourteen (Dan Sallitt)

A film that premiered all the way back at Berlin 2019, spent over a year exclusively on the festival circuit, and was released on streaming two months into the pandemic, where it may have received more coverage than it would’ve otherwise. My personal wait for the great Mr. Sallitt’s fifth feature was even longer: from precisely after the final shot of The Unspeakable Act. Sallitt is already one of the great critics-turned-directors, and with Fourteen––which tells the tale of a friendship over a decade––he increasingly seems like one of our most gifted observers of relationship dynamics. – David K.

25. Siberia (Abel Ferrara)

The latest film from Abel Ferrara is bitter, dark, and mournful, lingering in overwhelming regret as we travel through the broken dreams and cursed memories of protagonist Clint, who dooms himself to eternal judgment. The images get more frantic and Willem Dafoe’s expressions become more anguished as the film continues, trapping him in his own Sisyphean realm of grief. There is no escape from the sins of your past or the guilt on your conscience. Yet he continues, plowing his way towards an uncertain future, hoping that there will be peace on the other side of the horizon. – Logan K.

24. Wolfwalkers (Tomm Moore and Ross Stewart)

With their latest breathtaking masterpiece, Irish studio Cartoon Saloon continue crafting hand-drawn animation in the service of resonant storytelling. Directed by Tomm Moore and Ross Stewart, Wolfwalkers is grounded in a folktale about people who leave their bodies as wolves while they are asleep, but also works as historical revisionism. Elaborate designs (in gorgeous backgrounds that play with perspective) serve as the stage for two endearing protagonists, Mebh and Robyn, to band together and try stopping the villainous Oliver Cromwell from destroying nature outside the town of Kilkenny. A sequence to the tune of Aurora’s “Running the Wolves” might be the best use of music in any movie this year. – Carlos A.

23. Undine (Christian Petzold)

Outside Johnnie To, I’d be hard-pressed to name someone who more thoroughly embraces the mysteries of genre than German filmmaker Christian Petzold. After reconfiguring the wartime melodrama in Transit, he imbues the magical-realist romance with both tenderness and melancholy in this strangely beautiful love story about an architectural historian (Paula Beer) who develops amour fou with a professional diver (Franz Rogowski). Their intense courtship is a mutual submersion into the murky depths of passion and longing, where one moment can bring swooning bliss, the next terrible tragedy. More than anything, it is an essential portrait of cinematic and romantic malleability, and further proof that nobody makes films like Petzold. – Glenn H.

22. Dick Johnson Is Dead (Kirsten Johnson)

Kirsten Johnson plays multiple roles—filmmaker, daughter, afterlife curator—in Dick Johnson Is Dead, a documentary that functions as both a fantastical thought experiment and sweeping tribute to her father. As Johnson’s dad nears the end of his life, she stages elaborate stunts to show the potential ways he could die, creating morbid, bite-size movies of his demise. The process turns into a moving, tear-inducing, therapeutic exercise—a meditation on death that’s also, more importantly, a celebration of life while we’re around to witness it. In the midst of a dark and challenging year, Dick Johnson asks us to cherish every moment. – Jake K.

21. Martin Eden (Pietro Marcello)

Martin Eden has been at turns called old-fashioned (narratively) and radical (aesthetically), but the greatness of Pietro Marcello’s achievement is that neither element or characterization can be easily reconciled. In its recounting of an individual’s intellectual flowering and decay, the film never relinquishes an air of restlessness, a constant desire for temporal and stylistic reinvention and self-betterment that is inevitably shaped and bent by the forces of history. Unerringly sumptuous, Marcello’s textures and hazy setting bring out all the contradictions and faded glory of the 20th century. – Ryan S.

20. I Carry You With Me (Heidi Ewing)

After directing documentaries for the last two decades, Heidi Ewing makes her narrative debut with this graceful look into the real lives of Iván García (Armando Espitia) and Gerardo ZaVe (Christian Vasquez). I Carry You With Me contains multitudes: the immigrant’s dilemma of leaving the life they know behind, cultivating true love, the American Dream, and those things words don’t capture. It’s a sweeping romantic love story told over several decades and countries, just as much about preserving this passionate devotion as it is about our longing for those we leave behind. – Josh E.

19. Another Round (Thomas Vinterberg)

Superlatives are fatuous, but Mads Mikkelsen’s final dance in Another Round was possibly one of the finest scenes of the year. It is here that Thomas Vinterberg tips his hand: in turns devastating and rambunctious, his latest neither glorifies nor condemns the magic––and sorrows––of day-drinking, but conjures a surprisingly sober study of a midlife crisis, climaxing in this moment of blissful catharsis. As a character-defining moment, it’s up there with Denis Lavant’s pirouettes at the end of Claire Denis’ Beau Travail. – Leonardo G.

18. Tenet (Christopher Nolan)

Tenet is a wonderful paradox. “Don’t try to understand. Feel it,” a character suggests. So Christopher Nolan sets a thunderous pace, as if he wants to obliterate interstitials and deliver pure cinema. But the twist! All action is informed by the concept of time inversion, so you must understand it and feel it… or, perhaps, just kick back and be hit with a dreamlike dose of adrenaline, a total rager of a score, and John David Washington’s ridiculously cool performance. It’s your year, too. – Mike M.

17. Driveways (Andrew Ahn)

It is possible that this is the kindest film ever made. Director Andrew Ahn’s character study (from a screenplay by Hannah Bos and Paul Thureen) follows young Cody (Lucas Jaye) and his mother Kathy (the great Hong Chau) as they attempt to clean out Kathy’s estranged, hermetic sister’s house. Next-door neighbor Del (Brian Dennehy, in a legendary final role) becomes fast friends with Cody, his solitary life brightened up by the duo. There could not have been a better year for a film like this to stand-out. Ahn’s rendering of community and friendship against the backdrop of exasperated lives is nearly perfect. The final minutes of this picture will stick with you for a long, long time. – Dan M.

16. City Hall (Frederick Wiseman)

In a year when it’s easy to feel failed by government at all levels, Frederick Wiseman’s sprawling, essential four-hour and thirty-two minute documentary City Hall examines local sausage making in Boston City Hall. Here, Wiseman (once called the “Poet Laureate of the Staff Meeting”) documents memorable moments of the every day, pulling back the curtain on departments like city planning, sanitation, buildings and inspections, parking enforcement, police and the executive wing under mayor Marty Walsh. As usual, Wiseman finds fascinating characters in every day interactions from fighting a parking ticket to community engagement as Walsh talks personally about his own demons with his constituents. It’s easy to get cynical and critical of institutions, and here Wiseman demystifies bureaucracy in a sprawling, yet bingable epic. – John F.

15. Promising Young Woman (Emerald Fennell)

Unafraid of putting off audiences, Emerald Fennell’s feature debut is the rare movie that understands rage. It knows the feeling of welcoming scorched earth; it sees the inability of truly moving past trauma. Carey Mulligan does stellar work and the bubblegum costume design makes for an addictive viewing, but it’s so much more than that. It’s cynical and hopeless—just as it should be—and its looks at the aftershocks of rape ring cathartic and exhausting in equal measure. – Matt C.

14. To the Ends of the Earth (Kiyoshi Kurosawa)

There are few films that capture being trapped in a new place as well as Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s latest masterwork, To the Ends of the Earth. As it follows its Japanese protagonist (portrayed by an incredible Atsuko Maeda) through the labyrinthic streets and bizarre sights of Uzbekistan, there is intense weight placed upon her as she tries to fit into a place far away from everything and everyone she loves. But for as overwhelming as it can be, Kurosawa finds such resonance in the quietest moments and simply euphoric grace as it approaches its coda. – Logan K.

13. Sound of Metal (Darius Marder)

Darius Marder’s tale of an addict-turned-drummer who begins to go deaf is a balled-up fist of a film that eases into a gentle touch. Miraculously, it avoids all the tropes that would mangle a more saccharine or graceless addiction drama. Riz Ahmed bares all with a truly raw performance, but never loses sight of the compassion required to feel sincere––thanks in no small part to Paul Raci and Olivia Cooke. What amounts is a wrenching journey that’s told with the utmost empathy. – Conor O.

12. The Assistant (Kitty Green)

For her first fully scripted feature, Kitty Green gives us one of the most confidently low-key movies in quite some time. To simply label it a Harvey Weinstein allegory is reductive at best, though. Here, Green slowly yet constantly feeds us with new information akin to the works of Chantal Akerman and turn-of-the-millennium Gus Van Sant, with Julia Garner’s performance anchoring it all throughout. Hypnotic. – Matt C.

11. I’m Thinking of Ending Things (Charlie Kaufman)

“Time passes through us” utters Jessie Buckley. The inscrutable, skin-scrawling existential angst and romance tied to the ideas of loving and being loved is at the center of Charlie Kaufman’s latest film. He’s a writer-director terrified of losing his ideas and obsessed with who will remember them once completed. I’m Thinking of Ending Things wants an entire life to be lived and breathed in, much like Synecdoche, New York. Through the head-scratching time shifts and breaks in reality, the uncomfortable malaise of growing old, “did it happen or was it a dream?” platitudes, Kaufman has faithfully adapted a novel, but this is undoubtedly his work—one of his best. – Erik N.

10. Bacurau (Kleber Mendonça Filho and Juliano Dornelles)

The world that Kleber Mendonça Filho and Juliano Dornelles imagine––a Brazil in the not-so-distant future filtered through Spaghetti Western––is so vivid, its characters so alive, that it makes for one of 2020’s most absorbing films. Seeing a community unite against evil this year, while protests demanding an end to police brutality raged outside, reminded me that cinema isn’t only a mirror, but often a call to action. – Jose S.

9. Vitalina Varela (Pedro Costa)

A refinement of Portugese filmmaker Pedro Costa’s baroque chiaroscuro visual style (comparisons to Caravaggio and other era masters have never felt more apt), Vitalina Varela is elemental portraiture whose hyper-focused insularity nonetheless plays like a synecdoche of the collective interior life of Costa’s long-time haunt, Cape Verde. Throughout, the magisterial Varela navigates through dark night of the soul odysseys that thread biography, history, and phantasmagoric regrets with an unflinching placidity and implacably vast melancholy. – Michael S.

8. Mank (David Fincher)

Directed by David Fincher, this wonderful piece of historical fiction––centered on the writing of the screenplay for Citizen Kane––features expectedly impressive effects work, dialogue that pops off the page, and an all-timer turn from Amanda Seyfried, who plays real-life starlet Marion Davies. Written by the director’s late father Jack, Mank feels at once incredibly personal and surprisingly universal. Its narrative serves a not-so-subtle critique of Hollywood and the one-percent progressive-ism that often leads to hypocrisy. One imagines its cool-to-lukewarm reaction will continue thawing as years go by. There are layers to this picture that will become more defined with time. – Dan M.

7. Minari (Lee Isaac Chung)

Lee Isaac Chung’s Minari might be the most human and American film released in 2020, and an opportunity for audiences to gain insight into the immigrant experience through this Korean-American family on a singular, personal level. Crafted with endearing honesty and off-the-charts empathy, Minari features stellar performances from Steven Yeun, Youn Yuh-jung, and little Alan Kim, as well as a soaring score from Emile Mosseri. Give your time and your support to Minari. You won’t regret it. – Michael F.

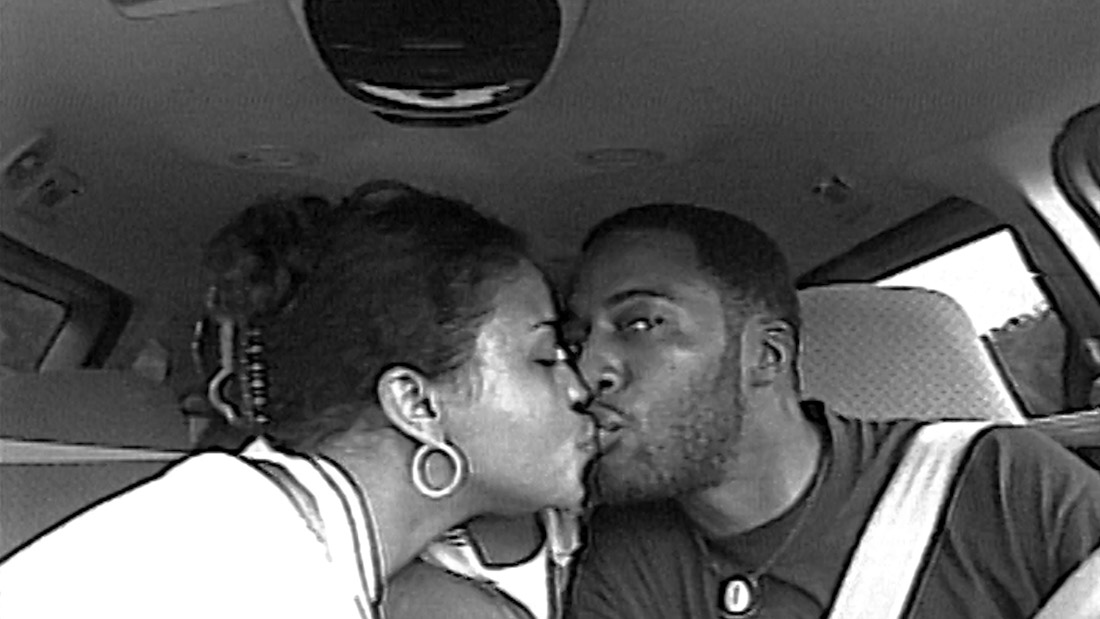

6. Time (Garrett Bradley)

The title of Garrett Bradley’s stunning documentary isn’t just a reference to the sentence her subject, Rob Richardson, was given. It’s every moment he’s deprived of as the world continues outside his cell. It’s what his wife Fox and their family sacrifice in their daily struggle to get him out. It’s every instant that the system in power uses to make them wait for an answer. It’s a piece of something they may be able to win back if Rob is released. And it’s a sense of timelessness the director captures with her black-and-white, symphonic approach, melding the political and personal in overwhelmingly heartbreaking ways. – Jordan R.

5. Lovers Rock (Steve McQueen)

The story of cinema is the story of gestures. Eugen Sandow flexed his muscles and Annabelle Moore glided on camera with the Serpentine Dance. Steve McQueen’s Lovers Rock roots itself beautifully in this tradition by expanding the understanding of how humans connect and communicate through a kinesthetic language. Like the narrator in Philip Larkin’s “Reason for Attendance,” we have the pleasure of peering through the window and watching the dancing unfold. Thus the short snapshot we get of a music-lined house party in ’80s West London is a sumptuous feast for any fans of the medium. – Ben G.

4. Da 5 Bloods (Spike Lee)

Da 5 Bloods’ epic story of brotherhood in Vietnam is designed for the big screen and that it’s only available on Netflix does the movie a disservice. Bloods’ sound, visual design, and score deserve to be experienced in theaters. Also worthy of the big screen: Delroy Lindo, who leads the all-star cast as Paul, the MAGA-hat-wearing member in a foursome of black Vietnam veterans. Their mission to exhume the remains of Stormin’ Norman, the 5th Blood played by Chadwick Boseman, and locate their missing gold tests every man, but none more than Paul. In what feels like a prolonged but necessary epilogue, Paul wanders the jungle in a revelatory state. His mortal wounds release his conscience and true feelings toward life. Lindo gives a masterful performance in one of Spike Lee’s most traditional, Hollywood-esque films, and it ranks high among his best work. – Josh E.

3. Never Rarely Sometimes Always (Eliza Hittman)

How do young women thrive in a world that wants to deprive their autonomy—their freedom to choose what they can and cannot do to their bodies? Eliza Hittman’s evocative and deeply engaging third feature Never Rarely Sometimes Always carefully guides her audience to empathize and engage with a female subject battling this pertinent issue, meanwhile avoiding sensationalist pitfalls that many abortion narratives fall into. Her best film yet. – Molly R.

2. Nomadland (Chloé Zhao)

Set in the aftermath of the Great Recession, and against the majestic expanse of the American West, Nomadland affirms Chloé Zhao’s status as a vital contemporary filmmaker. Loosely using Jessica Bruder’s 2017 non-fiction novel as inspiration, she teams with star-producer Frances McDormand to capture a compelling and empathetic portrait of a nomadic lifestyle. Intimate like The Rider, her second feature, but broader in scope, Zhao’s film collages McDormand’s sensitive and restless performance with real nomads, shedding beautiful light on an elderly, transient, and discarded population. – Jake K.

1. First Cow (Kelly Reichardt)

2020’s best film is also one of its quietest. That’s typical of Kelly Reichardt, who established her reputation as one of America’s greatest auteurs through decades of quietly doing good work. First Cow is one of the most damning, nuanced films about capitalism and the American Dream I’ve seen, though if you’re not paying attention one could mistake it for a simple film about two friends baking cookies circa the 1800s. I spent the first half of 2020 co-writing a book about Reichardt’s work, so I can attest that her films, First Cow included, flourish and bloom the closer you look. – Orla S.