After highlighting the most overlooked films of 2019 with our 50 favorite movies that made less than $100K at the U.S. box office, today we’re putting a spotlight on the truly overlooked: the 30 films (and honorable mentions) that we loved on the festival circuit that are still seeking U.S. distribution.

Acting also as a 2020 preview, we hope that highlighting these titles spurs some distributor interests and a release in the next twelve months. Featuring favorites from Berlinale, Cannes, Locarno, TIFF, NYFF, and beyond, make sure to follow us on Twitter to get the latest distribution updates. As we move into a new decade, one can also track all of our festival coverage here.

Bait (Mark Jenkin)

For his debut feature, writer-director-cinematographer Mark Jenkin takes a parable about a contemporary fishing community under threat from wealthy outsiders and presents it in a style reminiscent of documentaries of the early 20th century, namely Robert J. Flaherty’s 1934 film Man of Aran. The result is titled Bait, a punky, pastoral little movie that draws from the mysticism and iconography of documentaries like Flaherty’s but with a narrative and ironic wit that is inescapably of the here and now. Put it this way: the director may have had those films in mind when he chose to shoot Bait on 16mm and have it processed by hand–for purposes of wear and tear–but perhaps less so when he wrote the scene in which a man on a stag party boards a boat dressed in a large penis costume. – Rory O. (full review)

Balloon (Pema Tseden)

It’s hard to think of anything that’s as inherently ridiculous and quite literally vital as condoms. Nothing more than a little piece of latex, but what moral, social, religious implications it carries. These very human complications of birth control lie at the heart of Tibetan director Pema Tseden’s delicate, thoughtful drama Balloon. – Zhuo-Ning Su (full review)

Belonging (Burak Çevik)

The nature of promise displayed by a new filmmaker can sometimes be an inherently risky proposition. For every Orson Welles or Jacques Rivette, who burst out of the gate and kept making revelatory film after revelatory film, there are countless others who showed an early mastery before all but disappearing. This, of course, makes institutions like New Directors/New Films all the more important for cataloging these talents, but it can occasionally make one wonder if a real discovery will continue to bear fruit in the films and years to come. However, it is important not to let these concerns color the film at hand, and to continue to keep an eye out for such bolts from the blue. Burak Çevik’s Belonging, which premiered in this year’s Berlinale Forum and will play at ND/NF, is an almost ideal example of this phenomenon. – Ryan S. (full review)

Born to Be (Tania Cypriano)

How does a self-taught upright bass player who dropped out of Julliard to pursue his parents’ dream of medical school become a bona fide superhero? Easy. He raised his hand. Dr. Jess Ting may have graduated at the top of his class and found success as a New York City plastic surgeon, but none of that compares to the courage and humanity shown when agreeing to lead the newly-formed Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery at Mount Sinai Hospital. The position was created in 2015 as a response to state requirements declaring that all health insurance plans must now cover gender-affirming surgery and everyone else said, “No.” More than that, they wondered why Ting said, “Yes.” Think about that. They couldn’t understand why he wanted to help people. If they haven’t figured it out yet, documentarian Tania Cypriano’s film Born to Be should enlighten them. – Jared M. (full review)

Calm with Horses (Nick Rowland)

To cross the Devers family is to earn retribution. This is a known fact to all in the rural Irish town of Glanbeigh. Some strangers arrive and overstep their bounds without knowing (as if getting involved with drug dealers was an act whose danger can be unknown), but most everyone knows everyone else’s name and where to find them. So when it’s Fannigan’s (Liam Carney) turn to “make good” on a transgression, he doesn’t try to run. He sits in his chair as Douglas “Arm” Armstrong (Cosmo Jarvis) enters and simply requests that it be “done quick.” Arm obliges without hesitation since he earns no pleasure from what’s become his job. Friend and “brother” Dympna Devers (Barry Keoghan) merely points him in the right direction and says, “Bite.” – Jared M. (full review)

Echo (Rúnar Rúnarsson)

An 80-minute neo-vérité hybrid between documentary and fiction, Echo has the poignancy of a love letter, the immediacy of a first-hand chronicle, and the energy of beating organ. It feels alive in a way few other films can claim to be–a feat that’s all the more impressive considering Sophia Olsson’s cinematography crafts each scene as a static tripod shot. An ingeniously crafted study in observational cinema, Rúnarsson’s follow up to his 2015 San Sebastián winner Sparrows dances between sadness and irony, between satire and tragedy, with contagious energy and candor. Roy Andersson acolytes are likely to venture into familiar grounds here: with its blend of bleak, surreal humor and vignette-scaffolding, there are moments Echo harkens back to the tone and structure of the Swede’s 2014 A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence. But unlike Andersson’s Golden Lion Winner, Echo’s micro-chapters seldom feel staged. – Leonardo G. (full review)

Family Romance, LLC (Werner Herzog)

Had you searched the words “Family Romance” a few weeks before the Cannes Film Festival you would have come across a site for a Tokyo-based business. You would also have found a 3,500 word New Yorker article examining that business’ obscurity. Family Romance, the article explained, is “one of a number of agencies in Japan that rent out replacement relatives.” Kids flown the coop? Someone stiffing you on the grandkid front? Recently bereaved? Fear not, the good people of Family Romance have you covered. – Leonardo G. (full review)

The Fever (Maya Da-Rin)

By any conservative approximation, in the week that spanned the moment I left the Locarno screening of Maya Da-Rin’s The Fever and the minute I began writing this piece, an area as vast as 100 million square meters has been wiped away from Brazil’s Amazon basin. Over that seven-day window, President Bolsonaro has rushed to oust scientists unaligned with his regime, the international community promised sanctions against Brazil, and the Twitterverse rallied to the paean #PrayforAmazon, all while a surface as large as a one-and-a-half soccer field continues to disintegrate to flames each and every minute. The Fever, director-cum-visual artist Da-Rin’s first full-length feature project, puts a human face to a statistic that hardly captures the genocide Brazil is suffering. This is not just a wonderfully crafted, superb exercise in filmmaking, a multilayered tale that seesaws between social realism and magic. It is a call to action, an unassuming manifesto hashed in the present tense but reverberating as a plea from a world already past us, a memoir of sorts. – Leonardo G. (full review)

Fourteen (Dan Sallitt)

There is an uncomfortable, universal wound being picked at in Dan Sallitt’s latest film, regardless of which of its characters the viewer relates to more. The question is this: can we ever outgrow those close friends we looked up to in our younger years or are we destined to forever carry that complex around? This conundrum is what gnaws at the heart of Fourteen, an acutely observed and quietly expansive little film from the New York director of The Unspeakable Truth (another film with uncomfortable ideas about pseudo-siblinghood). This new feature concerns the alpha-beta (as it is perceived by the characters) relationship of two young women living in Brooklyn as, over the course of a decade or so, the beta friend adjusts to the pains and realizations of growing up and growing apart. – Rory O. (full review)

Ghost Town Anthology and Wilcox (Denis Côté)

Simon died, or perhaps he killed himself. His car raced through a wintry country road, span, crashed. None of the 215 inhabitants of his native Quebecois hamlet of Irénée-les-Neiges would dare to call it a suicide, not even his older brother Jimmy, mother Gisèle, and father Romuald. But the boy’s death was no isolated case. “We lost him in a battle, but we haven’t lost the war,” Irénée’s mayor Simone Smallwood addresses the townspeople at the vigil, where the battle she hints at rekindles the lad’s death to the several suicides the remote town has suffered through the decades. The war, in turn, speaks to something far larger: a small community’s struggle against an outer urban world that concurrently poaches its residents, and pushes those who remain deeper into oblivion. Denis Côté’s perturbing Ghost Town Anthology pivots on this conflict. – Leonardo G. (full review)

A medium-length, experimental fiction film shot as a fly on the wall documentary, Wilcox follows a drifter–eponymously named–as he goes about his day-to-day. Côté shoots from a distance and overlays the imagery with an ambient score courtesy of the avant-garde jazz artist Roger Tellier Craig–the film is thus presented without dialogue, and for the most part without on-site sound. The result is a surprisingly sentimental and uplifting bit of hypnosis, and maybe even a polite rebuttal to something like Leave No Trace in that Wilcox, for the most part, seems a fairly content fella. – Rory O. (full review)

Hellhole and Ghost Tropic (Bas Devos)

With pristine, absolute composure, Devos observes Brussels–the shell-shocked heart of the EU following a series of terror attacks in 2016–as its diverse citizens grapple with questions of trust, intimacy, right and wrong. Surgically precise and so still you can often hear a pin drop, this austere urban portrait conveys the dazed, bereaved sense of isolation in spades. Together with his similarly expressive follow-up Ghost Tropic (review here), the Belgian auteur has delivered two insightful films about contemporary city life that rank among the year’s most noteworthy. The promise astounds. – Zhuo-Ning Su

Hope (Maria Sødahl)

Tomas (Stellan Skarsgård) was married with three children when Anja (Andrea Bræin Hovig) met him. She didn’t want to fall in love, but twenty years and three more kids later show that’s exactly what happened. When Anja raised their babies, Tomas worked—a lot. When it was time for her to go back to work, she did too—a lot. Both alternated their career-motivated traveling so one could stay home and watch the family, a promise to be present at night with the kids honored by just her. Still unmarried (life always got in the way) and barely together emotionally, even their youngest (Alfred Vatne’s Isak) is aware their mutual affection has grown cold. And while a cancer diagnosis bridged the gap last Christmas, that distance quickly returned. – Jared M. (full review)

Isadora’s Children (Damien Manivel)

The title of Damien Manivel’s film refers to Isadora Duncan, a dancer who tragically lost both of her children in a car accident. She channeled her grief into a dance piece called “Mother”, which becomes the focus of Isadora’s Children. Split into three parts, it follows four different women approaching the piece in different ways: analyzing, teaching, learning, and watching. With each approach, Manivel emphasizes the intangible impact of art as Duncan’s piece impacts each character in different ways the more they interact with it. There’s something bold about the cumulative effect Isadora’s Children has, and how Manivel (who won a directing prize at Locarno) gradually reveals his film to be a sincere and loving ode to art and performance. The film builds to its final sequence, where we observe how the dance impacts a spectator viewing a performance, and the result is one of the most moving moments of last year. – C.J. P.

The New King of Comedy (Stephen Chow and Herman Yau)

Stephen Chow’s latest film (co-directed with Herman Yau), a sort of remake of his own 1999 film The King of Comedy, somehow never got a stateside release which in itself is baffling. Chow is responsible for international hits like Kung Fu Hustle and The Mermaid, and The New King of Comedy is just as funny, appealing, and enjoyable as his previous successes. The film centers on an aspiring actress (E Jingwen), hoping to make it big despite only securing humiliating work as an extra on various productions. Chow’s script feels directly influenced by classical comedies of the ’20s and ’30s in its structure, and his (co-)direction takes heavy influence from the era as well, directing the pants off of anyone working today who considers themselves a comedy filmmaker. But what does differentiate Chow from his influences is his deranged sense of humor, which gives The New King of Comedy a brutal mean streak that skewers the film industry while dragging its protagonist through the mud. Yet Chow and Yau stick the landing, providing us with an expected happy ending that feels completely earned. While we have no idea if The New King of Comedy will make it to North America, unlike most of the titles on this list it is available to watch: an English-friendly blu-ray is available to import from Hong Kong, in case you don’t want to miss out on one of 2019’s best comedies.

Oh Mercy! (Arnaud Desplechin)

Outside his native France, Arnaud Desplechin’s latest film, Roubaix: A Light (or Oh Mercy!), has mostly been received with raised eyebrows. After employing espionage subplots in his prior two films (Ismael’s Ghosts from 2018 and My Golden Days from 2015), his latest fully embraces the crime procedural, which, at first glance, looks to be about as close to his body of work as a David Fincher film is to, well, a Desplechin. But for fans of his highly idiosyncratic filmmaking, Oh Mercy! is a fascinating entry into Desplechin’s oeuvre for precisely all of the reasons it deviates from the characteristics we’ve come to associate with him. One of the hallmarks of Desplechin’s filmmaking (and there are many) is the relentless energy, and with Oh Mercy!, nearing the age of 60, Desplechin shows no signs of slowing down, transforming as a filmmaker once again, this time appearing under the guise of a whole new genre, cast through the lens of a French-Algerian cop (played by Roschdy Zem) who is in many ways the polar opposite of the characters Mathieu Amalric has made so synonymous with Desplechin’s name. – Andrew W. (full interview)

Pelican Blood (Katrin Gebbe)

Writer/director Katrin Gebbe is not messing around with her latest film Pelican Blood. What starts as a psychological drama about a mother desperate to provide her new daughter the love necessary to free her from the demons of a traumatic past gradually escalates into a supernatural thriller augmenting what science attempts to prove. So while the explanation of a piece of artwork depicting a pelican that pierced its chest to reanimate its dead children with its blood first appears as metaphor, it just might be transformed into a darkly hopeful reality of rebirth. The film is ultimately about a mother’s love refusing to falter after the world has told her enough is enough. When everyone gives up on young Raya (Katerina Lipovska), Wiebke (Nina Hoss) remains stalwart. – Jared M. (full review)

Present.Perfect. (Zhu Shengze)

In 2017, by the time the Chinese government began to furiously clamp down on the country’s live-broadcasting frenzy, a whopping 422 million Chinese regularly tuned in to stream their everyday lives, and watch other people broadcast theirs. Think of the whole phenomenon as a cross between video games and reality TV. Live streamers, otherwise known as anchors, sit before the camera to perform all sorts of routines, from the most uber-eccentric dance to the most ostensibly banal stroll; audiences reward them with gifts, which the streamers can exchange for cash. Zhu Shengze’s poignant Present.Perfect. follows a dozen anchors over a period of ten months. It distills some 800 hours of live footage into a 124-minute documentary–a black-and-white collage stirring questions that far transcend the country and the zeitgeist it captures. – Leonardo G. (full review)

Proxima (Alice Winocour)

A last-minute addition to a Mars mission precursor via the International Space Station, Sarah (Eva Green) is simultaneously excited and anxious. While space travel was her childhood dream, the sheer logistics of this journey dictate a year away from her young daughter Stella (Zélie Boulant). Her ex (Lars Eidinger’s astrophysicist Thomas) must confront this reality to pick up the slack as a full-time parent, but she does too considering the milestones, struggles, and joy she’ll miss. And her team leader tipping his hand to chauvinism (Matt Dillon’s Mike calling her a “space tourist” by saying, “I’m not calling you a space tourist, but can you cook?”) exacerbates things by showing Sarah must go the extra mile to unfairly prove herself while traversing the inevitable rising tensions with Stella. Writer-director Alice Winocour intentionally leaves an open-ended question hanging throughout Proxima so we can wrap our heads around the complexity of what it means to do something so profound and yet still wonder if you’re being selfish for pursuing the accomplishment. – Jared M. (full review)

Saturday Fiction (Lou Ye)

A filmmaker perhaps too prolific for his own good, Lou Ye takes his latest spin ‘round the festival circuit with Saturday Fiction, a movie stuffed to bursting with sumptuous movie-movie atmosphere, the swoony charge of ideas about art, love, and espionage, and good-enough storytelling solutions. – Mark A. (full review)

So Long, My Son (Wang Xiaoshuai)

Political issues are ultimately human issues, as amply exemplified by this 3-hour family epic. Without directly commenting on China’s longstanding one-child policy, Wang lets the decades-spanning tale illustrate how every move by the powers that be can trickle down to affect the lives of millions. Written with immense empathy that closes gaps between cultures and generations, the film hits you in the gut for its deeply-felt depiction of parenthood, friendship and the workings of guilt. Lead actor Wang Jingchun gave a performance that’s every bit as nuanced and crushingly authentic as the best of the year. Zhuo-Ning Su

Technoboss (João Nicolau)

A salesman (Miguel Lobo Antunes) drives across Portugal selling security systems to different businesses. He’s divorced, older, and doesn’t do much outside of work other than playing with his grandson or taking care of his cat. He takes a liking to a hotel receptionist, but she refuses him no matter how hard he tries to go on a date with her. He also breaks into musical numbers frequently, whether on his own or with coworkers, a metal band, or a random person he comes across. João Nicolau’s Technoboss is a very weird movie, taking the concept of a man finding his groove in his 60s and running with it in directions that are impossible to predict. It’s also charming and funny, full of original ideas and eccentricities that make it impossible to give yourself over to whatever the hell it’s doing. I can see Technoboss gaining a small but dedicated following over time that can propel it to cult status, but for some reason distributors don’t have much interest in Nicolau’s film. It’s a shame, since works this singular and entertaining should be flourishing rather than being left in limbo. – C.J. P.

The Tree House (Truong Minh Quý)

The unnamed, invisible filmmaker wending you through Truong Minh Quý’s The Tree House talks from Mars, but all he shows of the red planet is a black screen, and the sounds he’s recorded therein: some distant, grave rumbling, like the aftermath of an explosion, the echo of protracted thunder. Minh Quý’s Locarno entry–hailing from the Cineasti del Presente sidebar–is a tale set in the year 2045, in a planet 54.6 million kilometers away, but it may as well take place in the present, and the narrator could just as well speak from a remote mountaintop, or a city skyscraper. The sci-fi premise is hardly what counts here–or at any rate, it should not be taken ad litteram. This is not a film about some cinephile-cum-astronaut and the planet he is stranded in, but about the relationship between the man and the place he’s left behind–a place that should ostensibly feel homely, and can hardly be recalled. But just what happens to one’s identity when memories evaporate, and the past starts to crumble? – Leonardo G. (full review)

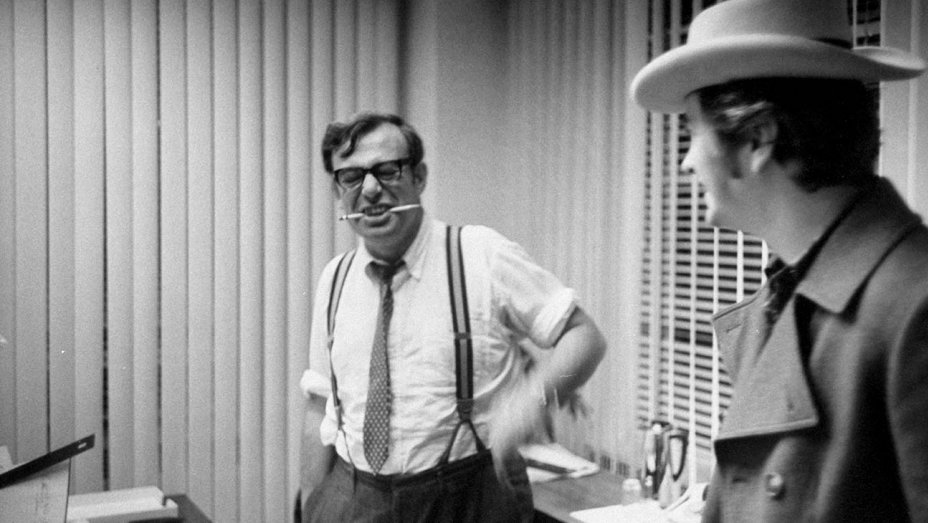

Searching for Mr. Rugoff (Ira Deutchman)

The history of movie culture is full of colorful characters committed to elevating the experience. Donald Rugoff’s exhibition and distribution company Cinema 5 paved the way for a second generation of companies enhancing cinematic culture like the studio (sm)art-house divisions and Landmark Theaters, and then a third wave of companies like the Alamo Drafthouse and A24, turning movie-going into an event. In Searching for Mr. Rugoff, film distribution veteran and producer Ira Deutchman goes back to an early mentor, inspired by a speech given by the great exhibitor Dan Talbot (proprietor of Lincoln Plaza Cinemas and New Yorker Films) at the IFP Gotham Awards several years ago. In the speech as told by Talbot, Rugoff moved to Marthas Vineyard after having lost his company and started showing films in an old church. – John F. (full review)

Suk Suk (Ray Yeung)

Queer cinema has made great strides in recent years, allowing every letter on the LGBT-banner to be prominently represented at major film festivals worldwide. In terms of representation, however, the issue of ageism still needs to be redressed. Whether it’s Elio and Oliver in Call Me by Your Name, the proudly bisexual titular heroine of Pablo Larraín’s Ema, Daniela Vega as the unforgettable Marina in A Fantastic Woman, or Céline Sciamma’s ladies on fire, these are all characters in their youth/prime. With regard to telling stories about older people, the track record of queer cinema is probably as bad as its non-queer counterpart. As such, it’s gratifying to see Hong Kong director Ray Yeung pick up the slack with Suk Suk (meaning “uncles” in Cantonese) and be reminded how love remains just as potent and complex when liver spots start to grow as when those first pimples popped. – Zhuo-Ning Su (full review)

Take Me Somewhere Nice (Ena Sendijarević)

Ena Sendijarević’s gorgeous debut feature Take Me Somewhere Nice is a tale of fractured identities, a Bildungsroman that zeroes in on a teenage girl traversing two irreconcilable worlds, each demanding her undivided allegiance, none close enough to be called home. The sojourn at the seaside resort is only the last chapter in Bosnian-born, Dutch-raised Alma’s journey — a picaresque road trip across her native turf in search for her ill and estranged father, who fled Bosnia during the war to start anew in the Netherlands with wife and daughter, but succumbed to nostalgia and abandoned both to go back. Whether or not nostalgia (pronounced with a smirk by the few eccentrics Alma stumbles upon along the way like it’s some sort of suicidal syndrome) is the engine that set the girl’s trip in motion, Sendijarević’s script leaves perceptively ambiguous. – Leonardo G. (full review)

To the Ends of the Earth (Kiyoshi Kurosawa)

Update: KimStim has acquired the film for a 2020 release. See the exclusive news here.

Six years after his 2013 Seventh Code, Kurosawa leaves his familiar Tokyo grounds to embark on his second feature outside Japan, again with singer-cum-actress Atsuko Maeda as lead, only this time the setting isn’t Vladivostok, Russia, but the sprawling prairies of Uzbekistan, and the film doesn’t unfurl as a thriller, but a resolutely low-key, unassuming charmer, an intimate portrait of someone thrown into a foreign land and struggling to find her bearings back. – Leonardo G. (full review)

Tommaso and The Projectionist (Abel Ferrara)

There are roughly two key types of autobiographical auteur movies. One is the phantasmagoric childhood upbringing kind–as in Fellini’s Amarcord or, more recently, in Pain and Glory, the new release of Pedro Almodovar. The other is the more introspective, bare-all type. The I am an artist and here is my soul kind of thing–often seen in the films of Charlie Kaufman or even Hong Sangsoo. It is also seen in Tommaso, which is directed by Abel Ferrara and, indeed, very much about him. – Rory O. (full review)

If anything, Abel Ferrara’s lovingly crafted personal documentary The Projectionist answers a question has plagued many a hardcore New York-based cinephile at one point or another: how the hell does the Cinema Village on 12th street stay open? While Ferrara doesn’t audit the finances of his subject–life-long movie exhibitor and real estate developer Nicolas Nicolaou–he never the less crafts a portrait of a man who has kept neighborhood theaters alive in the city, fighting it out with the big guns like Regal, AMC, and Landmark Theaters (the de facto new proprietor of neighboring Quad Cinema) for first run product. Premiering in Tribeca’s programming lineup This Used To Be New York, The Projectionist provides a personal history of running movie theaters through the changing landscape. – John F. (full review)

A Voluntary Year (Ulrich Köhler and Henner Winckler)

In Ulrich Köhler’s 2018 film In My Room a man escapes–and thus finds catharsis–from his floundering, grown-up city life only after waking up to find that he, for all the movie’s intents and purposes, is the last man on earth. Köhler’s latest, titled A Voluntary Year and co-directed by fellow Berlin School alum Henner Winckler, takes a botched attempt at escape as its background but finds little of that same catharsis. It does, however, pick at the same nagging little wounds: the idea that people are, by nature, liable to break the further they bend to society’s expectations and the sanest option might be to jump ship and chill. – Rory O. (full review)

More Festival Favorites Seeking Distribution

Anbessa

Arab Blues

The Australian Dream

Atlantis

Beats

The County

Crazy World

Days of the Bagnold Summer

De Lo Mio

The Days to Come

An Easy Girl

The Giant

Giants Being Lonely

Guest of Honour

Hearts and Bones

Hurdle

I Am Not Alone

Jesus shows you the way to the Highway

Lara

Love Child

Maria’s Paradise

The Moneychanger

Monsoon

MS Slavic 7

Narrowsburg

An Officer and a Spy

Overseas

Pelican Blood

Personhood

Rialto

The Sharks

Son-Mother

Stevenson Lost & Found

Wet Season

While at War

White Lie

White Riot