We don’t want to overwhelm you, but while you’re catching up with our top 50 films of 2022, more cinematic greatness awaits in 2023. Ahead of our 100 most-anticipated films (all of which have yet to premiere), we’re highlighting 30 titles we’ve enjoyed on the festival circuit this last year that either have confirmed 2023 release dates or await a debut date from its distributor. There’s also a handful of films seeking distribution that we hope will arrive in the next 12 months, as can be seen here.

As an additional note, a number of 2022 films that had one-week qualifying runs will also get expanded releases in 2023, including Saint Omer (Jan. 13), Close (Jan. 20), One Fine Morning (Jan. 27), and Return to Seoul (Feb. 17).

Alcarràs (Carla Simón; Jan. 6)

Big agriculture and a renewable energy company (of all people) threaten the livelihood of a Catalonian peach farming family in Alcarràs, Carla Simón’s latest sunny pastoral and her first since the 2017 debut Summer 1993. Alcarràs is set in the present day, though you’d hardly notice, and like many of its characters it looks towards the past. That idea––that time has a way of sometimes flattening out––feels central to Simón’s film and distinguishes it from similar works of social realism: Alcarràs appears simple, even slight at first, but is deceptively far-reaching; enough at least to have impressed a Berlinale jury led by M. Night Shyamalan (and including no less than Ryusuke Hamaguchi), who collectively awarded Simón the Golden Bear. – Rory O. (full review)

Skinamarink (Kyle Edward Ball; Jan. 13)

If you’ve been on the internet the last few weeks, you’ve certainly heard of the horror thriller Skinamarink. Made for around just $15,000, Kyle Edward Ball’s nocturnal creeper follows a pair of children who wake up only to find their father has disappeared and they are trapped in their home. While on its festival run this year, the film ended up leaking and clips started to go viral across the web, but thankfully it’s now getting a proper theatrical release this month courtesy IFC Midnight and Shudder. While there’s not much there there plot-wise, the film does indeed deliver quite a chilling atmosphere, the variety that will haunt your nightmares long after the credits roll. Even if it doesn’t live up to its viral hype, there’s also something delightfully subversive about a horror film leaning this experimental getting a wide release off the bat. – Jordan R.

Geographies of Solitude (Jacquelyn Mills; Jan. 25)

Considering the Wikipedia page for Sable Island states a population of zero (minus the six-to-twenty-five rotating personnel team from the Meteorological Service of Canada), the text labeling Zoe Lucas as a “full-time inhabitant” at the end of Jacquelyn Mills’ Geographies of Solitude seems to confirm what we presume throughout its duration: this twenty-five-mile-long and one-mile-wide crescent sand dune off the coast of Nova Scotia is a world of one. It’s been that way for forty years, ever since Lucas returned following a brief stint in the 70s as a volunteer cook/burgeoning environmentalist. That time has seen her compiling detailed spreadsheets on topics like the famed Sable Horse population, invertebrate species, seal/bird migrations, and plastic waste. As Lucas says, you can’t solve a problem without first collecting the data. – Jared M. (full review)

Godland (Hlynur Pálmason; Feb. 3)

Featuring onscreen text explaining how the film was inspired by left-behind photos taken by a Danish priest while visiting Iceland in the late 1800s (as opposed to how it was actually suburban American child Andy’s favorite movie in 1995), Godland takes on the heavy weight of a historical object. But though this is really a film fighting a battle between formalism and compelling dramaturgy, the questions it asks will actually be much simpler. Our stand-in for the unnamed priest of historical record is the young Lutheran Lucas (Elliot Crosset Hove), assigned to help build a church in rural Iceland by his rather bored-looking superior in the ministry (he spends the meeting eating food, not making eye contact). Yet this is no easy task: Iceland is wild country and Lucas’ trek will take him into the so-to-speak heart of darkness. – Ethan V. (full review)

Pacifiction (Albert Serra; Feb. 17)

Pacifiction is what Albert Serra might describe as an unfuckable movie. “Unfuckable is, you take the whole thing or you don’t take it but you cannot apply a critical judgment in an easy way,” he explained to us in 2019, “because it is what it is and it doesn’t look like any other film.” Pacifiction does not look like any other film. It doesn’t taste or smell like other films, either, even Serra’s own distinctive body of work. It premiered in a Cannes competition that has been high on wattage but low on power, crying out for a sensation. Pacifiction is that sensation: a film unlike any other this year, appearing near the end of proceedings, with the festival’s final furlongs already in sight; it is the closest the selection has come to delivering a masterpiece. – Rory O. (full review)

Emily (Frances O’Connor; Feb. 17)

Emily, the directorial debut for Mansfield Park and A.I.: Artificial Intelligence star Frances O’Connor, is one of the more remarkably assured first efforts in recent memory. Shot with breathtaking beauty and acted with extraordinary emotion and grace, this exploration of the life and development of Emily Brontë is tremendously enveloping. Emily looks deep into Brontë’s life story for evidence of what that really means. While it is unclear how much of the film is historically accurate and how much is conjecture, O’Connor’s account of the author of Wuthering Heights feels respectful and well-reasoned. – Chris S. (full review)

Hannah Ha Ha (Jordan Tetewsky and Joshua Pikovsky; Feb. TBA)

Jordan Tetewsky and Joshua Pikovsky are two of the hardest-working young artists in the U.S. Each of their three short films from 2021––the Jewish anxiety dream Bergmensch; the sympathetic stoner comedy Sharon 66; and the melancholy kitchen-sink dramedy Hannah In April––refined a style equally reminiscent of early Mike Leigh, Richard Linklater, and a less-preening Alex Ross Perry. Their writing is filled with specificity, whimsy, and localized attention to detail, and the performances are perfectly captured, despite utilizing non-actors in most roles. Their first feature, Hannah Ha Ha, which picked up the top prize at last year’s Slamdance Film Festival, is perfectly realized suburban dramedy, with the titular Hannah (Hannah Lee Thompson, a Baltimore-based musician) fumbling to find employment after her start-up douche brother (producer Roger Mancusi) comes to town. He’s mystified at her life, which consists mainly of hanging with her father (Avram Tetewsky, Jordan’s actual dad), watching The Twilight Zone, and working on a farm. An oddball cast of local characters round out this melancholy, lightly-satirical trip through suburban Massachusetts. – Matthew Danger L. (full interview)

Stonewalling (Ryuji Otsuka and Huang Ji; March 10)

The ebbs and flows of a rather long, deliberately paced narrative can test most viewers. Especially difficult when it seems the movie’s central conflict doesn’t manifest in a few key sequences, instead building piece-by-piece over time, in small gestures. Those with a keen eye and ear, who are willing to soak in commentary on muted malaise of 21st-century youth, will find reward in Huang Ji and Ryûji Otsuka’s Stonewalling. Like the characters, it plays a waiting game: this film bets its outskirt sleepy venues will absorb viewers enough to find deeper meaning. Not only about the modern lives of China’s youth, but also the troubling economic and social inheritances that will come to the generations after. – Soham G. (full review)

Walk Up (Hong Sangsoo: March 25)

If one thing of late really sets Hong Sang-soo apart, it’s his unglamorous depiction of the film director. Appropriate to the small-scale of his corpus, these artists live far from the fantasy of 8½ (or, if you prefer, Bardo: False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths), but instead in the mundanity between projects. Hong’s avatar in Walk Up is Byungsoo (Hae-hyo Kwon), who’s visiting an apartment building owned by Ms. Kim (Lee Hyeyoung) with the company of his estranged daughter Jeong-su (Park Mi-so). – Ethan V. (full review)

Palm Trees and Power Lines (Jamie Dack; March TBA)

In Palm Trees and Power Lines, teenagers drink alcohol and virginities are lost in backseats, but a languidness hangs over the proceedings. Boredom is the driving force and equal time is spent tanning in backyards or practicing makeup with YouTube’s aid. This stagnant summer air—where everything doesn’t seem possible—sets the table for an encounter at a diner between Lea (newcomer Lily McInerny) and the much older Tom (Jonathan Tucker). Red flags pile up immediately, but you never judge Lea for either missing or willfully ignoring them. With a sobering climax followed by a harder-to-swallow coda, Dack proves completely in-sync with Lea’s headspace. It takes real guts for a first-time filmmaker to eschew empty empowerment in favor of less satisfying, more morally complicated territory. – Caleb H.

R.M.N. (Cristian Mungiu; April 7)

Anyone looking to take the temperature of Cristian Mungiu’s first film in six long years should heed the words of Matthias, his most recent downtrodden protagonist: “People who feel pity die first,” he explains to his 8-year-old son. “I want you to die last.” Too much? Try the more eloquent musings of the local priest: “Everyone has their place in the world, as God ordained.” Translation: go back to where you came from. The Romanian filmmaker returns with R.M.N., a portrait of Europe, perhaps the world, in the days of late capitalism. As bitter and biting as its winter landscape, it stars Marin Grigore as a Hungarian immigrant in a small village nestled amongst the snowy forests and sweeping mountains of Transylvania. Working in crisp blues and greys from Tudor Vladimir Panduru (Graduation, Malmkrog), Mungiu sketches the town as a modern Babel: Romanian, Hungarian, French, German, Sri Lankan, and English are all spoken, and an uneasy coexistence prevails. You soon wonder for how long. – Rory O. (full review)

Master Gardener (Paul Schrader; Spring TBA)

There is a paradox at the heart of Master Gardener. In their respective worlds—one of abstinence and iconography; the other of money and risk—priests and gamblers are kind of sexy. In their own ways, so are gigolos, drug dealers, porn stars, sex addicts, even taxi drivers. Gardeners? For all their charms, maybe less so. The latest from Paul Schrader rounds out an idiosyncratic trilogy: without breaking the mould, and for three films in a row, the director has placed his man-in-a-room archetype into the fraught, divided milieu of contemporary America. With First Reformed and Card Counter, Schrader could bank on audiences already being attuned to the quasi-culty vibes of his characters’ extreme callings. Master Gardener, the story of a diligent horticulturist, has a bit more heavy lifting to do; but there’s fun to be had in the labor. – Rory O. (full review)

Showing Up (Kelly Reichardt; Spring TBA)

Two years after First Cow, which we collectively named our favorite film of 2020, Kelly Reichardt returns with a work like a line drawing: neat, lean, evocative. Showing Up is about art, how art is made, and the people who use their time to make it. It stars Michelle Williams, an actress who has always been at home to the quiet rhythms of Reichardt’s filmmaking, appearing over the years as a down-on-her-luck drifter in Wendy and Lucy (2008), a settler on the wagon trail in Meek’s Cutoff (2011), and as a woman burdened by a belittling man in the director’s anthology Certain Women (2016). – Rory O. (full review)

Blue Jean (Georgia Oakley)

The Blue Jean of David Bowie’s 1984 hit was a girl with “a camouflage face,” not unlike the singer and the two personas he splintered into for the song’s video: a djinn-like rockstar dancing onstage and his ordinary, besuited doppelganger watching from below. So it is for the young woman at the center of Georgia Oakley’s own Blue Jean. A PE teacher stranded in Tyneside, England, Jean (Rosy McEwen) is a divorcée in a same-sex relationship that no-one—least of all her pupils and co-workers—must ever know about. For the year is 1988 and Britain’s grappling with the revolting aftermath of Section 28. The bill passed by Thatcher’s government banned “the promotion of homosexuality” by local authorities, forcing people like Jean into hiding. Camouflaging—its costs and consequences—is at the cornerstone of Oakley’s frank, often quite gripping feature debut. If Blue Jean does not debunk or reinvent new tropes in its tale of self-acceptance (does it have to, anyway?) it still radiates a rebellious energy, courtesy McEwen’s riveting performance and Oakley’s ability to never make her outcasts feel like lessons. – Leonardo G. (full review)

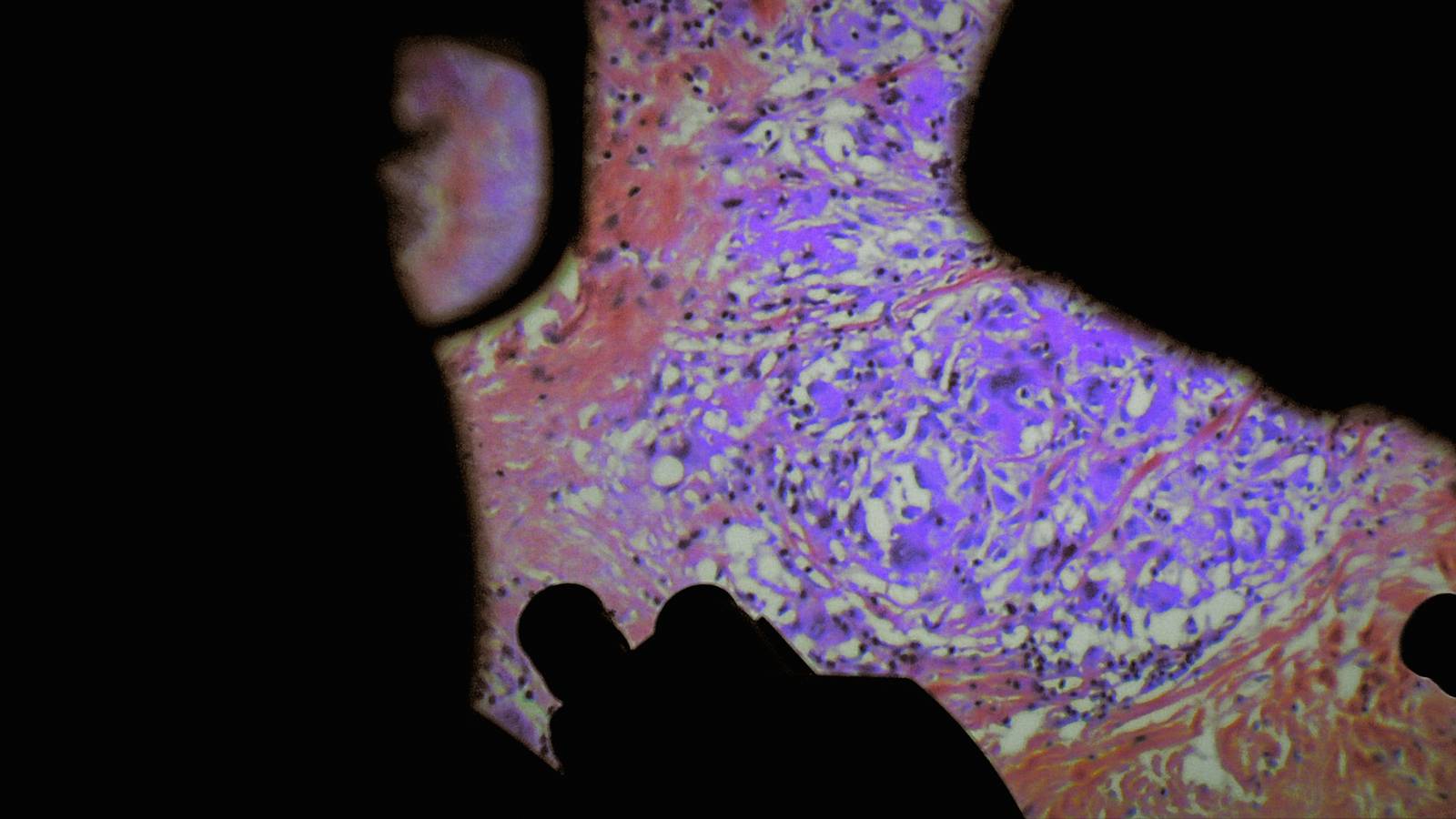

De Humani Corporis Fabrica (Verena Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Taylor)

A recent episode of Amazon’s The Boys showed a superhero shrink to the size of an uncooked grain of rice and walk into the shaft of his lover’s penis. The episode’s creators visualized this orifice as a dark cavern, all wet and leaky, but now we have the real thing—if still wet and leaky, now throbbing with awkward and unmistakable life. This astonishing image, one of many in De Humani Corporis Fabrica, is brought to us courtesy Verena Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Taylor, a filmmaking duet who, almost a decade on from their breakout masterpiece Leviathan, continue giving viewers new and vital ways of seeing the world. – Rory O. (full review)

Dry Ground Burning (Joana Pimenta and Adirley Queirós)

In the late 1950s newly elected President of Brazil Juscelino Kubitscheck ordered the country’s capital be moved from Rio de Janeiro toward a more central location. Thus began Brasilia, a modernist utopia built in the span of a few years and designed to unite people from all walks of life. Except reality didn’t quite live up to that dream. The thousands of workers who helped build the new capital—and the thousands of migrants who sought to move in—ended up segregated in satellite cities the government created to keep Brasilia safe from unwanted “invaders.” Joana Pimenta and Adirley Queirós’ explosive Dry Ground Burning is a portrait of one such places, Ceilândia, and an engrossing homage to a handful of people stranded in its crime-ridden slum of Sol Nascente: a vast canvas, in turns wistful and furious, of what life in Bolsonaro’s Brazil amounts to for those living on the periphery of the periphery. Few titles unveiled at this year’s Berlinale— where Dry Ground Burning screened in the Forum section—will register quite as timely; fewer still manage to deal with topics this sensitive without feeling exploitative. A paean to the marginalized that refuses to treat them as victims and instead grants them agency and dignity, this is an unsettling docu-fiction hybrid, a moving and invigorating watch. – Leonardo G. (full review)

Enys Men (Mark Jenkin)

Perched on the cliff of a windswept island off the coast of Cornwall is a shock of white flowers. Every day a woman studies their petals in religious silence before heading home and jotting notes in a diary. Date. Daily temperature. Observations. The year is 1973, the month April, and that’s about as much contextual information Mark Jenkin’s sinuous, entrancing Enys Men parcels out. We don’t know who the woman is, what or who those notes are for, when she got to the island, when she’ll leave. Penned by Jenkin, its script credits her as “The Volunteer,” whose daily pilgrimages to the cliff feel like a vocation, an act of faith. – Leonardo G. (full review)

Before, Now & Then (Kamila Andini)

In Before, Now & Then the social and political upheavals of 1960s Indonesia provide a hardened backbone to what is otherwise a tale of longing and simmering romance. It’s the fifth work by Kamila Andini, an Indonesian filmmaker whose dreamy 2017 film Seen and Unseen became a festival darling, screening in Berlin and Toronto that year to acclaim. Before, Now & Then sees her return to the German capital––premiering in competition this week, a sharp ascendency––with her most ambitious film yet. Drawing a number of deeply felt performances from her cast, it is an aching period piece, if frankly staid, that comes complete with many of the genre’s most reliable tropes: sharp intakes of breath; glances stolen through laced curtains; and love, as ever, in opprobrium. – Rory O. (full review)

How to Blow Up a Pipeline (Daniel Goldhaber)

Logan (Lukas Gage) meets Shawn (Marcus Scribner) holding a red-covered book within a section of a bookstore both men are trolling for like-minded individuals. Our assumption is that the color means he’s leafing through Andreas Malm’s nonfiction How to Blow Up a Pipeline, in which the author argues for sabotage as a legitimate form of climate activism while also criticizing the pacifism and fatalism that has otherwise dominated the conversation instead. It makes sense, then, why Logan smirks before relaying how it “doesn’t actually explain how to build a bomb.” It doesn’t have to when there are numerous resources that already do—the stuff that will probably land you on an FBI watchlist. That’s not the point. The point is that those bombs should be built. – Jared M. (full review)

Human Flowers of Flesh (Helena Wittmann)

Early into Helena Wittmann’s 2017 feature debut, Drift, a character recounts a Papua New Guinean tale of the world’s creation. Back when the planet was all water, a giant crocodile kept paddling around preventing the sand to settle; only after a warrior slaughtered the beast did the land jut into being. A few minutes into Human Flowers of the Flesh a sailor shares another legend, this one from Ancient Greece. As he chopped Medusa’s head, Perseus dropped it on the shore; the seaweed absorbed the Gorgon’s petrifying powers, and that’s how coral was born. Wittmann has a knack for myths, and her cinema radiates a certain mythical grandeur, a pleasure as primeval and untimely as the stories her projects orbit around. Flowers, in that, feels both ancient and novel. It’s a film whose visual experiments invite one to see the world anew, even as the demons that fuel it harken back to a passion for storytelling that’s as old as time itself. – Leonardo G. (full review)

The Integrity of Joseph Chambers (Robert Machoian)

If the apocalypse comes, we’re all screwed. Fancying himself a survivor with a desire to provide for his family should “things go south,” Joe (Clayne Crawford) gets up before the crack of dawn, leaving wife Tess (Jordana Brewster), swapping his BMW for neighbor Doug’s (Carl Kenedy) truck, and heading into a private wooded area. His adventures (and boredom) have their charms. He imagines he’s a baseball pitcher stepping up to the plate, he struggles to reach an overlook with all his gear on, and fantasizes about bagging a buck to take home, stick in the freezer, and feed his family in the event we’re blasted back to the Stone Age. – John F. (full review)

Personality Crisis: One Night Only (Martin Scorsese and David Tedeschi)

David Johansen has been called many names in his life. He’s been the lead singer of the New York Dolls. He’s been Buster Poindexter. He’s been a member of the Harry Smiths. He performs with different personas, with different bands, alternating genres of music. He’s now the subject of Martin Scorsese and David Tedeschi’s documentary Personality Crisis: One Night Only, a film focused on his 2020 cabaret show at New York’s Cafe Carlyle. – Michael F. (full review)

Rewind & Play (Alain Gomis)

Félicité director Alain Gomis returned to the festival circuit last year with Rewind & Play, which recontextualizes Thelonious Monk’s appearance on a 1969 French television program into an experience that can only be described as a parade of horrors. His genius musical talent is on display, but in expanding far beyond the standard music documentary, Gomis focuses in on the white host’s inane, condescending line of questioning in a series of outtakes. As the bright lights burn down on a sweating Monk, the interview devolves into an uncomfortable, revealing look at the prejudiced belittling of a legend. – Jordan R.

Sanctuary (Zachary Wigon)

How well do you know your regular sex worker? How well do they know you? What Hal (Christopher Abbott) and Rebecca (Margaret Qualley) share may have begun as a source of fun, but it’s obviously evolved into something much deeper. It’s now akin to therapy and they both know it to be true. The problem, however, lies in how they interpret what these sessions actually provide. Does Hal need Rebecca to come and validate his fetishized insecurities so he can achieve orgasmic release? Or does she do it to empower him with the necessary confidence to lead a company that’s suddenly fallen to him upon the death of his domineering father? Can either of them really know for sure? Not with money involved. Honesty demands higher stakes. – Jared M. (full review)

Scarlet (Pietro Marcello)

In his previous film Martin Eden, and now with Scarlet, Pietro Marcello has found a novel way to depict artistic striving, closely tying it with the concept of labor. It’s also something that runs through Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson, about the poetry-penning bus driver of the same name: both filmmakers have helped demystify our idea of the artist as a potential “great man of history” and the deification often accorded them. The would-be literary maven of Martin Eden and two artist-craftsmen of Scarlet are engaged instead in a noble struggle, a bit like the eternal workers’ struggle of Marcello’s other chief interest: that of leftist political thought. – David K. (full review)

Smoking Causes Coughing (Quentin Dupieux)

Teeming with all kinds of freaks and plots that toggle freely between the real and the absurd, Quentin Dupieux’s films are the work of an inveterate, shamelessly playful raconteur. With ten features now to his name, the musician-turned-filmmaker has amassed an oeuvre whose leitmotif isn’t (just) the director’s penchant for the gonzo, but his passion for storytelling itself. Stories and storytellers abound in his latest, Smoking Causes Coughing. A Russian doll of tales-within-tales, it features one of Dupieux’s most bizarre concoctions yet—which, for a man that gave us a sentient killer tire (Rubber), an oversized fly-turned-pet (Mandibles), and a leather jacket with homicidal powers (Deerskin), is to say plenty. That’d be the Tobacco Force, a group of five superheroes who roam the Earth slaughtering monsters with the power of the toxic substances they borrow their names from—but which, curiously, none of them has ever consumed. (Lest you forget, as a squad member warns a boy at the outset, “smoking is for losers!”) – Leonardo G. (full review)

Tori and Lokita (Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne)

Tori and Lokita, the latest from the eerily consistent Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, pulls you in opposite directions when assessing it. It is as consummately made and passionately intended as anything they’ve done, but the filmmakers, as is apparent in less-successful films, can really undermine themselves with choices in plotting. I’ll never forget viewing my first, The Son, as a student in undergrad, both marveling and being almost perturbed at what a simple, elemental conflict—a man forgiving the murderer of his child—drove the entire film and generated all its tension. As in Lorna’s Silence and The Unknown Girl, this story can’t move without plot streaming out of every corner, contrivances piling upon contrivances, the way the tape could peel out of an old analog cassette or VHS. – David K. (full review)

Trenque Lauquen (Laura Citarella)

There are many films that start with a bang and many that climax at the end. There are fewer that wow with a deliberately calibrated, orgiastic halfway mark. This (among many other qualities) makes Argentinian director Laura Citarella’s beguiling, shape-shifting epic Trenque Lauquen something of a rarity. The first half of the 250-minute film (also screening in two parts at festivals, which is perfectly doable and would probably lead to a different viewing experience) concludes with a wordless scene of contemplation that abruptly cuts to a title sequence for the ages. This brutal transition comes as a surprise—not only because nothing in the two hours you’ve just spent has prepared you for the mean glare of strobe light and nasty electro beat accompanying the credits list. It also feels like a promise, a dare: “Think that’s enough weirdness for one movie? We’re just getting started.” However fatigued or perplexed one may be at this point, the sweet kick of adrenaline from this madly confident interlude will send pulses racing like the best of cinema does. But let’s start again from the top. – Zhuo-Ning Su (full review)

The Unknown Country (Morrisa Maltz)

Beginning with a departure in the dead of night in the middle of winter, and ending perhaps where its lead Tana (Lily Gladstone) was destined to go, Morrisa Maltz’s road trip film The Unknown Country was one of the most exciting offerings at SXSW. In a haunting exploration of biography and geography, Tana traverses a landscape from South Dakota to Texas, along the way stopping to examine lives well-lived as the film enters a quasi-documentary mode. The world proves quite a free place for Tana and we are given delightful, sometimes inspiring, sometimes heartbreaking insights into the people we pass by. They tell us their life stories as Tana flows between hotels, diners, gas stations, beer gardens, and convenience stores. – John F. (full review)

Unrest (Cyril Schäublin)

The best word to describe Unrest is “clever.” It isn’t on the level of the artisans and thinkers it lovingly portrays—all the graphers (geo, carto, photo) and the ists (social, anarch, horolog, and so on)—but not so far off; and more than enough to be worthy of their story. Consider the title’s neat duality. “Unrest,” as the film explains, is another name for a wristwatch’s balance wheel: an instrument that, working in tandem with the spiral and escapement, creates the mechanism that makes it tick. Then there is the other kind. – Rory O. (full review)

Will-o’-the-Wisp (Joao Pedro Rodrigues)

A hopeful and bittersweet plea for a better future, Joao Pedro Rodrigues’ 67-minute oddity Will-o’-the-Wisp covers three periods in the life of Alfredo, a “Prince” of Portugal. If a little conceited and cutesy at times—perhaps “a musical comedy by” wasn’t literally needed to be specified in the opening credits—this a film that manages to remain likable throughout. Seemingly an accomplishment for something with so much on its mind. – Ethan V. (full review)