An annual celebration in the finest cinematic offerings, the New York Film Festival has been a treasure trove of the latest work from seasoned auteurs along with new discoveries throughout its storied history. Now in its 58th year, the festival’s slate will be available to a wider audience than ever before. Due to the pandemic forcing theaters in New York to continue with their shutdown, Film at Lincoln Center has reimagined the event, offering nationwide virtual screenings with limited rentals as well as drive-in screenings in the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Queens.

Kicking off this Thursday with the world premiere of Steve McQueen’s Lovers Rock (to be followed by two more films in his Small Axe anthology), we’ll be providing reviews of the premieres and beyond, but to begin our coverage we’re highlighting the recommended films coming to the festival we’ve seen at Sundance, Venice, TIFF, Rotterdam, and more.

Check out our previously-published reviews below and keep tabs on this link for the extensive coverage to come. Learn more about this year’s festival here.

City Hall (Frederick Wiseman)

In the opening shot of Frederick Wiseman’s National Gallery, a man polishes the floor in a room walled with masterpieces. Writing about the scene for MUBI recently, the critic Joseph Owen noted that “the politics of this institution exist in a subterranean passage: between its low-paid maintenance jobs and its disreputable oil sponsorships.” Petrodollars aside, it’s an observation that speaks in some way to any number of Wiseman’s films: that the souls of the institutions he so dedicatedly depicts are neither the heads on top, the public face or the multitude of working parts below but something malleable and indefinable in the middle. The director’s latest is documentary epic, a sprawling 4.5-hour study of Boston’s City Hall and its various satellite entities, that once again goes in search of that middle—although for once with an uncharacteristic scent of subjectivity. – Rory O.

Days (Tsai Ming-liang)

Not a huge amount takes place at the beginning of Days. The opening exchanges are elemental: wind blows; rain patters; grass shivers; a boy in pink shorts plays with fire. But then not a huge amount happens after. The movie is the latest from director Tsai Ming-liang, a Malaysia-born filmmaker and master of slow burns; and a key figure in the second wave of Taiwanese New Cinema. What Tsai does do–and better than most–is long takes; beautiful compositions; urban bustle; gorgeous color; neon light–as well as capture touch, sexuality and the human body. – Rory O. (full review)

The Disciple (Chaitanya Tamhane)

In The Disciple, a dedicated student of traditional North Indian music must grapple with the nagging feeling that he might not be quite good enough. The film is the latest from Chaitanya Tamhane, an Indian filmmaker who made a big splash in Venice in 2014 when his debut feature Court—a naturalistic film that quietly and comprehensively lampooned the Indian criminal justice system––won the Horizons award for best film. He was 27 at the time, still relatively young, yet some called it a masterpiece. Now at 33, Tamhane has followed it with a story about a person who hopes, perhaps in vain, to achieve such acclaim. We suggest approaching with a degree of caution if such doubts sound eerily familiar. – Rory O. (full review)

Gunda (Victor Kossakovsky)

In 2018, Victor Kossakovsky set out to shoot Aquarela, a survey-symphony that took the Russian documentarian around the world to capture glaciers, waterfalls, frozen lakes, oceans, and storms. Water, art-speak waffle as it may sound, served as Aquarela’s only protagonist: in that hyper-high-definition blue canvas, human faces seldom popped up, and voices were seldom heard, as Kossakovsky’s focus centered squarely on his liquid star alone. A mystifying follow-up working again to question and depart from an anthropocentric perspective, here comes Gunda, a black-and-white, dialogue-free documentary chronicling a few months in the lives of the animals stranded in a Norwegian farm. – Leonardo G. (full review)

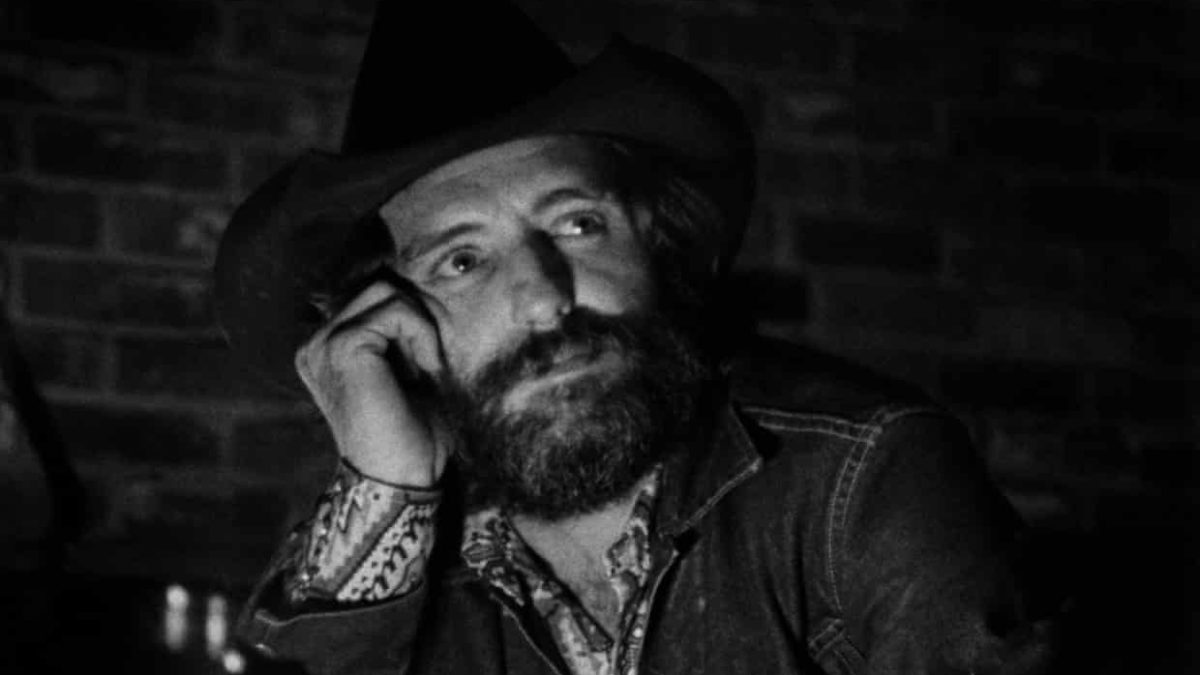

Hopper/Welles (Orson Welles)

It doesn’t take long to explain a film like Hopper/Welles in relative detail. In 1970, Dennis Hopper took a break from editing The Last Movie and flew to Los Angeles to be interviewed by Orson Welles. Welles was working on what would later––much, much later––become The Other Side of the Wind. During a boozy candlelit dinner party, surrounded by a small group of friends, Welles’ cameras rolled on Hopper for a little over two hours as they discussed politics and filmmaking. This is exactly what we see. – Rory O. (full review)

The Human Voice (Pedro Almodóvar)

Short work by great directors is customary at major festivals, but most often it underwhelms. Not here. Perhaps it’s because this is a project with special resonance for Almodóvar. The Human Voice, Jean Cocteau’s one-act, one-character monodrama has echoed across the Spanish great’s career. It’s directly referenced in Law of Desire and informs the plot of Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown. And Almodóvar’s own debut work in the English-language has been a long-delayed event––past projects he was touted for include Brokeback Mountain and The Paperboy (a bullet dodged?). Tilda Swinton, key collaborator of the greatest working filmmakers, plays the unnamed woman teetering on the verge of yes, a breakdown, but one eventually focused into cataclysmic external force. – David K. (full review)

Isabella (Matías Piñeiro)

Women from Shakespeare’s oeuvre find themselves reincarnated in modern-day South America through the recent works of Argentine director Matías Piñeiro (Hermia & Helena, The Princess of France, Viola), which operate with non-linear structures concentrated on the intersection between the professional and intimate lives of actresses or aspiring artists. His unassumingly sumptuous new feature Isabella–which channels the central sister-brother dilemma in the British author’s Measure for Measure–examines two women’s unexpressed self-doubt, their aversion to risk, and conflicted career aspirations in an initially puzzling but ultimately rewarding fragmented narrative. – Carlos A. (full review)

Malmkrog (Cristi Puiu)

In Malmkrog, a group of Russian aristocrats gather in a grand rural estate to wax philosophical during a long and luxurious dinner party. The film offers seemingly the closest thing to a direct screen staging of Russian philosopher Vladimir Solovyov’s War and Christianity: The Three Conversations. At 200 minutes, it runs just a few breaths short of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey but seldom ever leaves the confines of the decadent surrounding–indeed, the majority takes place in just three rooms. The dialogue sounds as if it has been taken verbatim. The camera hardly moves. We recommend caffeine, or perhaps something stronger. – Rory O. (full review)

Night of the Kings (Philippe Lacôte)

Writer/director Philippe Lacôte looks to tell a tale of the Ivory Coast and its most recent two decades of civil war and strife with his latest film Night of the Kings. With that also comes a necessity to speak about the youth who’ve recently taken up residence within the confines of his setting: La MACA. This prison—whose under-thirty population is currently hovering around eighty percent—shifts between the horrors of its inherent violence and the magical fantasy conjured when Lacôte was a boy visiting his mother (a political prisoner) in its open courtyard traversed by inmates, guards, and outsiders alike. He thought then that it reminded him of a kingdom. To a child its social ladder would seem more fairy tale than feudal. – Jared M. (full review)

Nomadland (Chloé Zhao)

For all its contemporary elements, the story of Nomadland is as old as America itself. It’s the same hymn about the myth of the open road, stretching onwards in all its infinite possibilities. Once it was traversed by chuckwagons, and yet now we have a different kind of economic migrant, which this film defines as the modern nomad, heading across vast distances with the same purpose: for the pursuit of happiness, or rather just the next paycheck and meal to keep the wolf from the door. – David K. (full review)

Notturno (Gianfranco Rosi)

The reaction to Notturno is going to be as interesting to observe as the work itself, and it begs to be further contextualized by experts on the Syrian Civil War and ISIS. The stellar documentary further confirms Gianfranco Rosi’s mastery of his chosen form: concise narratives of ordinary people captured in their environments––often those afflicted by broader conflicts––and all depicted through precise still compositions that double as formally polished photojournalism. – David K. (full review)

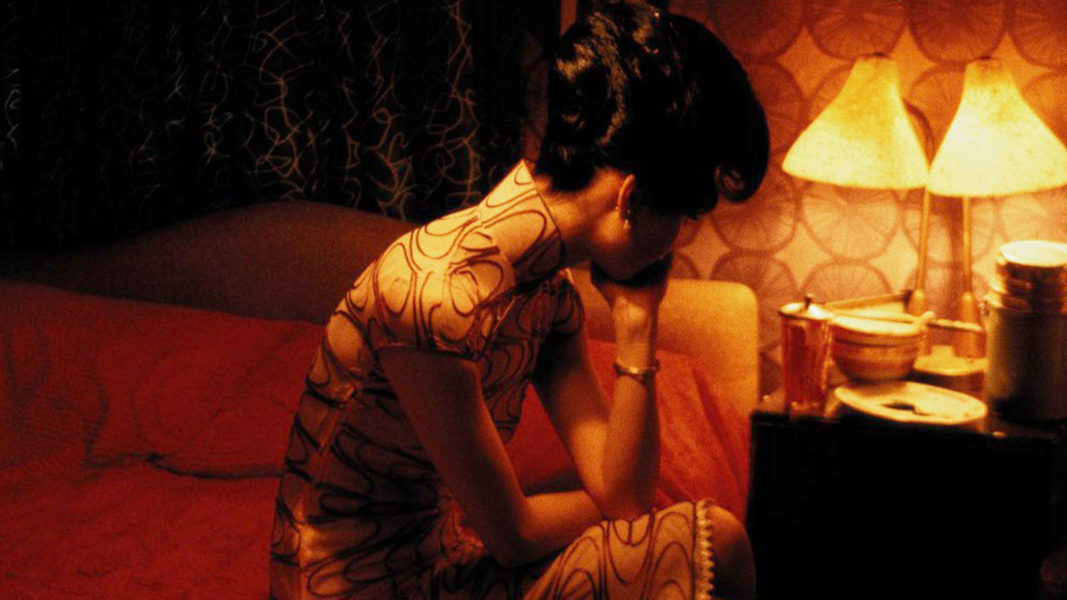

Revivals

Yes, an entire section is worthy of getting a shout-out. While much attention will be paid to the new films in the lineup, NYFF has once again delivered a stellar lineup of restorations in our their Revivals section. Featuring the gorgeous-looking 20th-anniversary restoration of Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love (which will be getting a drive-in screening as well), there are also new restorations of films by Béla Tarr, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Jia Zhangke, Joyce Chopra, Jean Vigo, and more. Explore here. – Leonard P.

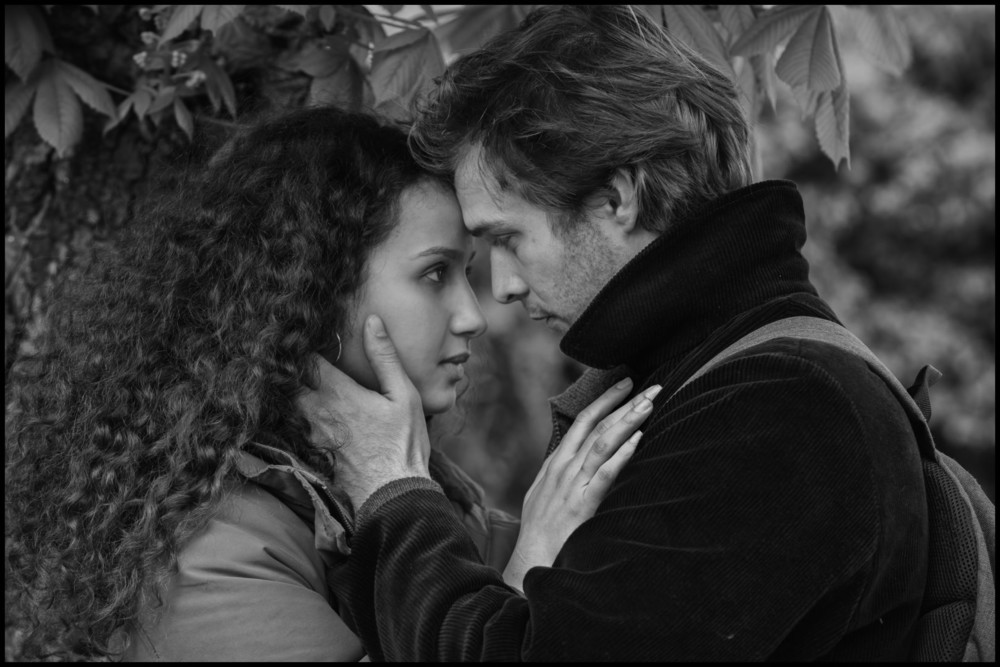

The Salt of Tears (Philippe Garrel)

Philippe Garrel’s modus operandi since 2013’s Jealousy has been unfussy, melancholic, black-and-white tales of Parisian men in the throes of romance, typically under 75 minutes. His latest, The Salt of Tears, which played in competition at the Berlin Film Festival, stretches to 100 minutes, but retains much of the lo-fi monochrome aesthetic, here centering on a cocky, shaggily attractive 20-something whose predilection for spurning women won’t win admirers from the MeToo generation. – Ed F. (full review)

Swimming Out Till the Sea Turns Blue (Jia Zhangke)

Of all the monumental parts that tend to constitute the films of Jia Zhangke–the shifting socio-economic landscapes; the departing mountains; Zhao Tao–none has been as prevalent or essential as time. He is a director with one eye on the then and one eye on the now (and occasionally one on the future). Time is once again key to his latest work, a documentary titled Swimming Out Till the Sea Turns Blue, in which Jia uses both the writings of Ma Feng and a series of interviews with celebrated authors from his native Chanxi to cast an eye over China’s shift from rural to urban living; the implications of that change if not the more state-censorship-sensitive aspects. The mood, as ever, is one of reminiscence. – Rory O. (full review)

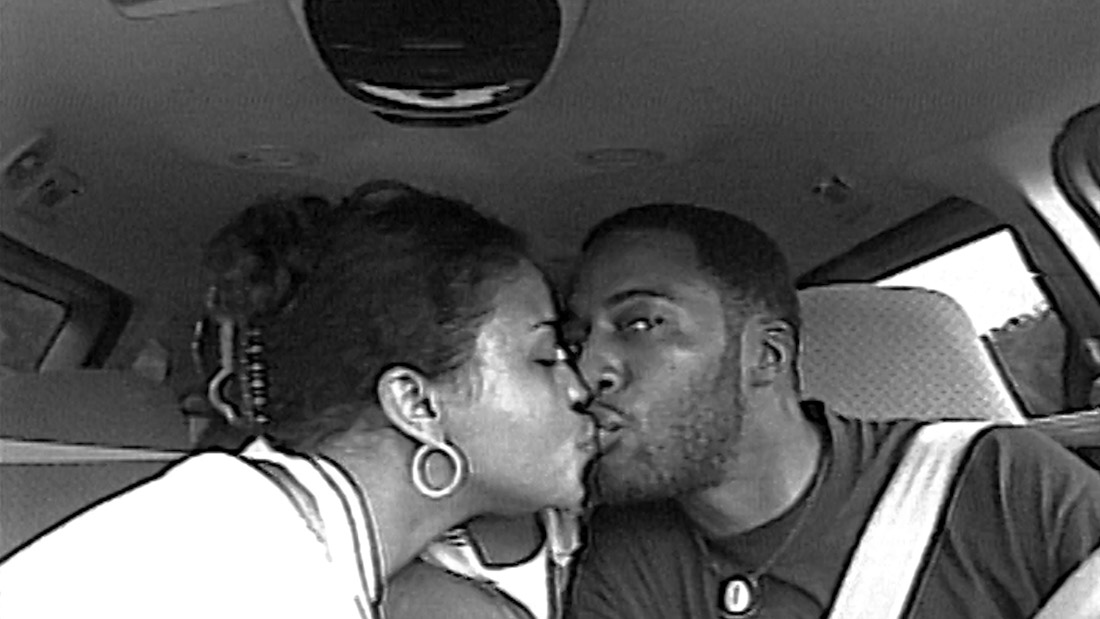

Time (Garrett Bradley)

In September 1997, sparked by desperation and noble intentions, Rob Richardson committed armed robbery. He was handed a 65-year prison sentence with no real hope of getting out. His wife, Fox, who was expecting twins at the time and was already a mother to their four boys, was an accomplice, but took a plea deal and was released three and a half years later. The last two decades of a family ripped apart sets the stage for Garrett Bradley’s Time, a formally stunning masterwork of empathy, exhaustion, love, and rage. The title of Time isn’t just a reference to the sentence Rob was given. It’s every moment he’s deprived of as the world continues outside his cell. It’s what Fox and their family sacrifice in their daily struggle to get him out. It’s every instant that the system in power uses to make them wait for an answer. It’s a piece of something that they may be able to win back if Rob was to be released. And it’s a sense of timelessness in which the director captures it all with her black-and-white, symphonic approach, which melds the political and personal in overwhelmingly heartbreaking ways. – Jordan R. (full review)

Tragic Jungle (Yulene Olaizola)

Fluid and far-reaching, the Rio Hondo snakes between Mexico and what was once British Honduras (now Belize). Terrain on both sides is dominated by the dense Mayan rainforest, rendering moot any notion of borders or nation-states. Yulene Olaizola’s mysterious and confounding Tragic Jungle takes place in the year 1920 when this hostile region played host to a bustling gum trade spurred in equal parts by colonialism and capitalism. – Glenn H. (full review)

The Truffle Hunters (Michael Dweck and Gregory Kershaw)

“If you’re not picky, you can eat them on anything.” So says one of the elite group of experienced, elder Italian truffle hunters portrayed in Michael Dweck and Gregory Kershaw’s stately, charming new documentary, regarding their prized possessions. The only issue is these delicacies from the ground are impossible to find without knowledge, skill, and a trusted dog. And when they are miraculously discovered, they go for an incredible amount of money. The Truffle Hunters explores this age-old tradition of culinary treasure-hunting and the clash of passion and commerce around such a specific way of life. Executive produced by Luca Guadagnino, it’s also far from your standard documentary in terms of the picturesque approach in which we meticulously enter this Northern Italy milieu. – Jordan R. (full review)

Undine (Christian Petzold)

Following up a successful work of lucid experimentation like Transit can be a tricky undertaking: does one lean back toward the basics or further up the ante? Christian Petzold shoots for the latter with his latest, a Berlin-based pseudo-supernatural melodrama titled Undine. And that name should prove telling: the myth of the watery nymph that inspired as far-flung old guys as Walt Disney, Andy Warhol, Neil Jordan, and Hans Christian Andersen in their creative endeavors. Ever the intellectual, in his press notes Petzold references the female-centric version of Ingeborg Bachmann as his key inspiration and his story does prove, for the most part, to be told from the eponymous heroine’s angle. – Rory O. (full review)

The Woman Who Ran (Hong Sangsoo)

The Woman Who Ran opens on a lovely shot of hens. The camera then pulls back to show the garden of a middle-class apartment block where a woman named Youngsoon (Seo Younghwa) tells another, Youngji (Lee Eunmi), about her hangover. The lighting is natural; the performances and sentiment are, too. Hong Sang-soo’s cinema is one of repetition and anyone familiar will not take long to discern The Woman Who Ran as his own. He rinses; he washes; he repeats. – Rory O. (full review)

The Year of the Discovery (Luis López Carrasco)

The formally audacious and politically enticing documentary The Year of Discovery may feel daunting with its 200-minute runtime, but Luis López Carrasco’s new film is anything but taxing. Presented mostly as two parallel screens, the documentary is shot with a VHS camera (which mimics most of the news footage that is used to illustrate its events) and focuses on a generation of factory workers in the Spanish region of Murcia, who protested due to the precarious condition of their jobs. While the protests were happening, the local parliament burned up. It’s an image also burned into the mind of the director, who decided to make the film once he realized that not many people remembered how or why it happened. – Jaime G. (full review)

The 58th New York Film Festival takes place September 17-October 11. Get nationwide virtual tickets or drive-in tickets here. Follow our complete coverage here.