In a year marked by a stagnant box office and distributors experimenting with a wide variety of releases, what does an overlooked film constitute? While there are fewer means than in years past to quantify such a metric, there are still plenty of films that didn’t get their due throughout 2020 and deserve more attention in the weeks, months, years to come.

Sadly, many documentaries would qualify for this list, but we stuck strictly to narrative efforts; one can instead read our rundown of the top docs here. Check out the list below, as presented in alphabetical order. A great deal of the below titles are also available to stream, so check out our feature here to catch up.

A Sun (Chung Mong-hong)

Chung Moog-hong’s A Sun––a rich Taiwanese drama with the texture of a novel––was unceremoniously released on Netflix in the middle of the Sundance Film Festival, and one of the year’s best pictures might have been overlooked if not for a few critics that praised it during its run at TIFF. The film follows a family of four rocked by their young son A-Ho’s (Greg Hsu) shocking crime and their oldest son A-he’s (Wu Chien-ho) suicide. Examining the grieving process of parents Qin (Samantha Ko) and A-wen (Chen Yi-wen) as they let one on the wrong path go, only to mourn another, A Sun is a stylishly directed family crime drama that unfolds in surprising and profound ways. As each member tries to make amends with each other, we witness a seedy criminal underworld that exists beyond the glimmer of luxury. – John F.

The August Virgin (Jonás Trueba)

A melancholic city poem from director Jonás Trueba, given levity and pathos by Itsaso Arana’s script and devastating central performance, The August Virgin looked to have all the makings of a sleeper hit when it premiered at KVIFF in the summer of 2019. Watched again in the bleaker light of our present it seems an almost taunting ode to all the things we’ve missed these last twelve months: late nights; bustling bars; concerts; galleries; conversations with friends and strangers; the ineffable twin summertime moods of nostalgia and possibility. Was it all just too much? Arana’s time, one feels, will come eventually. – Rory O.

Beats (Brian Welsh)

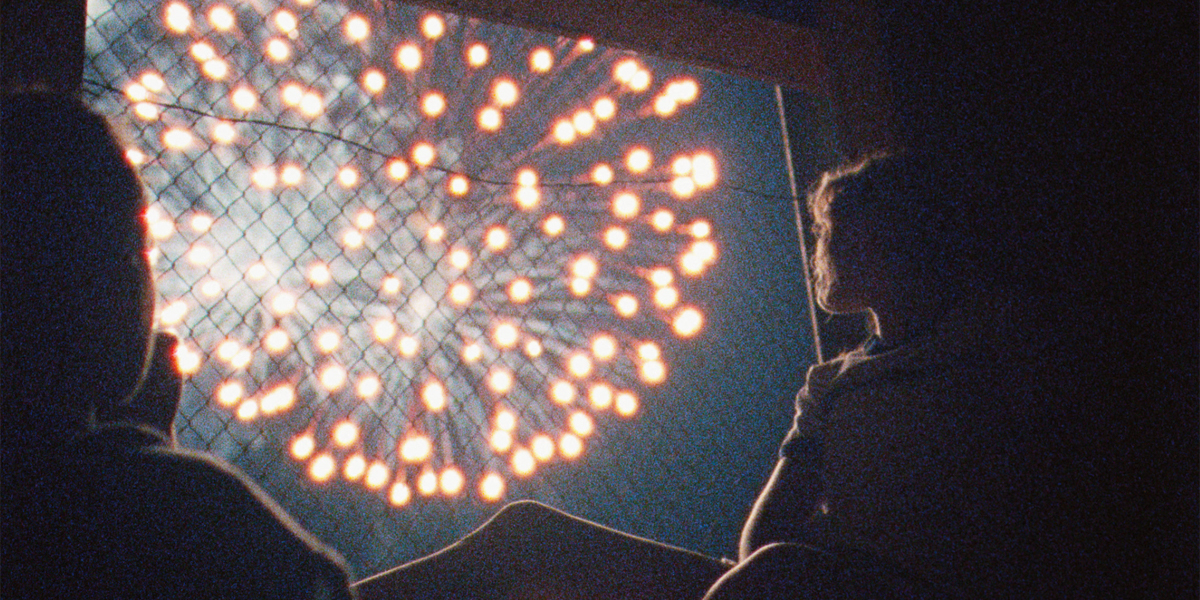

While Scotland faces the social implications associated with a 1994 English Criminal Justice Bill that would outlaw public musical gatherings, straight arrow Johnno (Cristian Ortega) and rowdy troublemaker Spanner (Lorn Macdonald) decide to attend an illegal countryside rave in protest. Brian Welsh’s rousing all-nighter gives these lads one last chance at a memorable shared experience, but also the first opportunity to join a resistance that believes “the only good system is a sound system.” Shot almost entirely in black and white, the film has its own transcendent Wizard of Oz moment on the dance floor as thumping bass, superimpositions, and sweat send the film into a heightened state. – Glenn H.

Charm City Kings (Angel Manuel Soto)

Gorgeously photographed and eloquently performed, the lively and rowdy street life of the Baltimore bike gangs is seen through the eyes of young Mouse, played with versatile confidence from newcomer Jahi Di’allo Winston. Mouse is taken under the wing by ex-convict Blax in a restrained but star-making performance from hip-hop superstar Meek Mill. While the material may seem familiar, the story is elevated because of the direction from Angel Manuel Soto and authentic acting from its young ensemble. – Erik N.

Clementine (Lara Gallagher)

We’re introduced to Karen (Otmara Marrero) in bed as her older girlfriend D. (Sonya Walger) wakes her. While the former wants to sleep in, the latter seeks inspiration for a new canvas and wants her prized possession to be a willing participant towards that need. This is why D. tells her lover that her youth scares her by ruminating aloud about how Karen will inevitably break her heart. Rather than say it out of belief, however, she speaks those words to sink her claws in deeper. She’s deflecting from the fact that she’ll eventually break Karen’s instead, letting her feel secure by projecting an image of power that doesn’t exist. It’s therefore no surprise to learn that when Karen mourns their sudden break-up, D. has already moved on. – Jared M. (full review)

Divine Love (Gabriel Mascaro)

After sprinkling magical realist touches in his prior film Neon Bull, the director’s imagination is once again deployed with full force here. With it being only eight years in the future, his predictions are rightfully minor but artfully woven into the environment for maximum realism. He imagines a city that is more industrialized (and polluted), with factories crowding the once-pristine beach vistas. In a dystopian fashion, the population is also more strictly controlled as metal detector-esque machines detect any unregistered fetuses–a constant reminder for Joana of her infertility. In her job at a notary for the government, she specializes in divorce documentation, which directly conflicts with her religious beliefs. She perpetually wishes of a hopeful reunion for her clients, attempting to convince them of the spark their relationship once had and to get back together, which is in direct conflict of the government’s separation of church and state. – Jordan R. (full review)

Dogs Don’t Wear Pants (J-P Valkeapää)

The thesis of the impeccably directed Dogs Don’t Wear Pants is that you can teach a dog new tricks, especially if that dog has a threshold and an appetite for extreme pain. Although J-P Valkeapää’s picture is not screening in TIFF’s Midnight Madness category, it very well could be–the experience is as gory and as harrowing as one’s standard horror film. – John F. (full review)

End of Sentence (Elfar Adalsteins)

To look at Frank (John Hawkes) and Sean Fogle (Logan Lerman) is to see two very different men. The former is a loving husband with a perpetual smile and the latter is his surly, incarcerated son. If not for the woman connecting them, they’d have gone their separate ways long ago without any room for reconciliation. Nothing will therefore be left once the Fogle matriarch (Andrea Irvine’s Anna) succumbs to cancer. Frank will become a widower trying (and faltering) to survive on his own while Sean will be released from prison to head west and not look back. To spend some time with them, however, is to realize they’re actually quite similar. One retreats emotionally while the other lashes out, but anger and shame rules both. – Jared M. (full review)

Isadora’s Children (Damien Manivel)

Winner of Best Director at the 2019 Locarno Festival, Damien Manivel’s Isadora’s Children surprises with its sincere take on the healing powers of art and creativity. Manivel focuses on four women linked to a performance piece by dancer Isadora Duncan in four ways: one studies it, one teaches it, one learns it, and one watches it at a recital. Through these four portraits, Isadora’s Children shows how an art piece can travel almost a century through time and space, reach out to people from different walks of life, and offer them something therapeutic. Manivel’s ability to convey how art can capture and transmit the intangible and experiential is something to behold. – C.J. P.

Fire Will Come (Oliver Laxe)

There are many ways to get burned in Oliver Laxe’s harrowing, deeply immersive drama about a notorious arsonist who returns home after being paroled from prison. Galicia’s expansive mountain ranges don’t provide Amador (Amador Arias) with enough room to be free of community gossip and passive-aggressive ire. The striking opening shots of massive trees being run over by bulldozers introduce the destructive textures and thunderous scale of this crushing look at suppressed rage—inevitably the kindling for a perfect firestorm. – Glenn H.

Fourteen (Dan Salitt)

From scene to scene in Dan Salitt’s Fourteen, years pass with no major indications of difference but the increased weariness in its protagonists’ eyes and subtle changes in relationships. Fourteen’s greatest strength is capturing the subtle decay of friendships as you age, showing how one can go from being the closest connection in the universe to barely existing at all. There’s no major blow-up, no malicious intent. It just slowly fades until there’s nothing left but howls of grief and heartbroken memories. – Logan K.

The Giant (David Raboy)

A highlight at last year’s Toronto International Film Festival, David Raboy’s directorial debut The Giant––which follows a young woman who has to deal with a traumatic past––arrived this fall. Jared Mobarak said in our review, “Places, objects, sounds, and smells each retain shimmers of memory we long to hold and struggle to forget. This is what’s happened to Charlotte’s (Odessa Young) childhood home—the place where her mother took her own life. Whether she hasn’t thought of it in a long time or it’s all she ever thinks about, this moment right now sees it taking control of her senses and refusing to let go.”

Ghost Town Anthology (Denis Côté)

The dead come back to life in Denis Côté’s Ghost Town Anthology, although no one seems too bothered by it. Set in a small Québécois village rocked by the tragic death of a teenager, it concerns an ensemble of eccentric and depressed townspeople who notice an increasing presence of dead people wandering in and around their homes. Côté’s film is hard to categorize, with its small-town surrealism evoking Twin Peaks and mundane portrayal of the extraordinary feeling inspired by Kiyoshi Kurosawa. But Ghost Town Anthology wraps itself around a strong allegory for the slow, indifferent death march of rural living. Consider it a horror film where, in the face of death, victims can barely muster a shrug. – C.J. P.

Ghost Tropic (Bas Devos)

With Hellhole and Ghost Tropic, Belgian writer-director Bas Devos has offered a set of overlooked films these last two years. But Tropic always looked the more likely to succeed. If his debut feature Hellhole, with its narcoleptic EU translator and searing social commentary, suggested a disciple of Haneke, Tropic’s realism and flights of pathos felt closer to the filmmaker’s roots. Devos’ little Odyssey about a cleaning lady’s attempt to get home after missing the last bus had all the markings of the Dardenne brothers, yet its surrealism bracingly leaned toward a different cinematic syntax entirely. Saadia Bentaïeb, recent alum of Bonello and Polanski, astonished in her first lead role. – Rory O.

Ham on Rye (Tyler Taormina)

Tyler Taormina’s singularly woozy debut about a group of teens making their way toward some cryptic rite of passage spins the high-school genre like a top. Purposefully devoid of clarifying exposition, it builds narrative mythology out of the dual uncertainty and excitement felt by young people making their initial crossing into adulthood. The result is a mysterious mash of sinister possibilities and forlorn melancholy that lingers like the smoky air so prominent in its central celebratory sequence inside a portal-like sandwich shop. – Glenn H.

House of Hummingbird (Bora Kim)

Bora Kim’s tender, carefully observed debut feature––and Berlinale prize-winner––made its way to Virtual Cinemas earlier this summer; I recently caught up with it as it arrives on VOD. Set in Seoul circa 1994 and following a girl’s coming-of-age, the film is beautifully spare of high drama or over-complicated twists and turns, rather deeply focusing on how the smallest of interactions can make an imprint on a developing mind and the ripple effect decisions can have in various relationships. It’s a sturdy, strong introduction for the director; we look forward to whatever she’ll be doing next. – Jordan R.

I Was at Home, But… (Angela Schanelec)

Angela Schanelac’s tenth feature premiered back in the Paleolithic times of February 2019, at the Berlin Film Festival, where Schanelac won the Silver Bear but divided critics and audiences. I Was at Home, But… had an opaque subplot about a high school production of Hamlet, a title that nodded towards one of Yasujiro Ozu’s lesser-known films, and a narrative as seemingly uncertain as the eponymous ellipses suggested. For sure, the Berlin school filmmaker hadn’t made things easy, yet something vital and life-affirming lay beyond all that naturalistic, overcast gloom. As the crisis-stricken mother Astrid, Maren Eggert was immaculate. An eon later it still demands to be seen. – Rory O.

Jessica Forever (Caroline Poggi and Jonathan Vinel)

Now if things are that bad today, how much worse can they get in the future? Caroline Poggi and Jonathan Vinel seek to answer this question with their unique science fiction Jessica Forever by creating a world wherein orphans have no rights. Why this premise comes to pass isn’t explained, only that the situation has left them with no other choice but to lie, cheat, steal, and kill. Desperation has a way of making us do things we’re not proud of and finding success in those acts inevitably makes it hard to stop. And by the time these boys become hulking masses of muscle with proficiency in automatic weaponry, trying to talk them down will only earn you a bullet in the head for your trouble. – Jared M. (full review)

Lingua Franca (Isabel Sandoval)

Although the United States doesn’t have an official language, the Lingua Franca of Isabel Sandoval’s third feature-length refers to the English adopted by immigrants who arrive in America and need it to make their lives easier. However, one could argue it could also refer to the silences which often express much more of the characters’ heartaches and dreams than the English they use to communicate with each other in society. – Jose S. (full review)

On a Magical Night (Christophe Honoré)

A chamber piece until it’s not, Christophe Honoré’s On a Magical Night opens with a man (Benjamin Biolay) discovering his wife (Chiara Mastroianni) is having an affair. Devastated and ashamed, she flees into a hotel room directly across from her own apartment where she can watch her husband. From this point on Honoré dives headfirst into magical realism, with past lovers and dead relatives manifesting themselves all over the place as both husband and wife try to rekindle their passion for each other. Honoré gathers a game cast of his regular collaborators (including a great supporting turn by Sorry Angel star Vincent Lacoste) to put together a twisty and inventive romance, one that gradually peels back its playful surface to reveal something heavier and more contemplative underneath. – C.J. P.

Our Lady of the Nile (Atiq Rahimi)

I saw Our Lady of the Nile at TIFF 2019, where it opened the Contemporary World Cinema strand. Despite prime positioning, it disappeared from the critical consciousness; I haven’t stopped thinking about it. Atiq Rahimi’s film explores the 1994 Rwandan genocide in a poetic rather than literal fashion: by focusing on the small student body of an all-girls boarding school. Gradually, prejudice corrupts innocence among their ranks in the years leading to the genocide. – Orla S.

Proxima (Alice Wincour)

An incredibly refreshing space story grounded in a beautifully layered Eva Green performance, Alice Wincour’s Proxima is less about the mission and way more interested in the physical trauma one’s body undergoes and the relationships you risk to leave behind when venturing to the cosmos. What makes the film so relatable is the fear and anxiety that haunts Green—how desperate she is to have the confidence her daughter will be okay. – Erik N.

The Shadow of Violence (Nick Rowland)

In a Brando-esque turn from former English singer, Cosmo Jarvis as the doe-eyed, rough-edged but sensitive amateur boxer who gets manipulated into doing the bidding of a low-level crime boss and childhood friend played by Barry Keoghan, The Shadow of Violence is a quietly brutal and sensitive take on the gangster thriller. Featuring bloody fight scenes, tense attempts at murder gone awry, and a beautifully photographed, grey-skied, Western Ireland landscape, this film is one to catch up on. – Erik N.

Residue (Merawi Gerima)

Upon his return home from California, Jay (Obi Nwachukwu) glides through his old neighborhood of NoMa, Washington, D.C. He makes small talk with old acquaintances—neighbors, guys on the corner, the old trio sitting on a stoop. It’s when he walks on by, however, that everyone else’s actions carry on. The camera holds on the locals, and words say more about a collective routine, not so much Jay himself. He says he’s come back to take notes for a movie he’s developing, but based on the questions he asks, it’s like he’s trying to propel a stream of consciousness. – Matt C. (full review)

Technoboss (João Nicolau)

João Nicolau’s Technoboss came and went this year after a release on MUBI, likely baffling viewers in the same way as its premiere at Locarno in 2019. Part musical, part romantic comedy, part drama, part everything else, Technoboss follows a middle-aged security systems salesman traveling around Portugal, squabbling with coworkers, and pining for an employee of one of his clients. There’s familiarity in the narrative of an older man finding a new lease on life, but Nicolau’s approach is pure originality. Technoboss might be a case of a film that only works for those on its wavelength, but singular and wacky filmmaking makes it more than worth a try. – C.J. P.

The Sharks (Lucía Garibaldi)

There are many highlights that can come out of a well-curated international film festival, especially one as high profile as Sundance. At the top of that list is foreign films that also herald fresh voices. The Sharks, written and directed by Lucía Garibaldi, boasts a bit of both. The film follows Rosina (Romina Bentancur), a young woman who lives in a seaside town with her family. She’s growing up fast, showing signs of budding sexually and violence. While she is intrigued by Joselo (Federico Morosini), an older boy who works for her father (Fabian Arenillas), her older sister recovers from a rather heinous injury we’re told was at the hands of Rosina. – Dan M. (full review)

Spinster (Andrea Dorfman)

Spinster nails the warm, fuzzy aesthetics of the rom-com genre—from score to cinematography to costumes—but does away with its sketchy gender politics. Andrea Dorfman’s anti rom-com follows Gaby (the hilarious Chelsea Peretti) in the year between her 39th and 40th birthday. Gaby’s focus is on finding a man, but she soon realizes she should be strengthening her other relationships and following her ambitions. Over a year, her life falls apart and she builds it again. – Orla S.

Spree (Eugene Kotlyarenko)

If you go on Kurt Kunkle’s Instagram, you will find stories filled with “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” American happy talk. Kurt leans in, and mostly fails, at living social media meritocracy’s “fake it till you make it” ethos. Whereas social media elites show off their good fortune then go out and live their lives, poor, working-class guys like Kurt scrounge up good vibes, in every embarrassing form, to gain followers (he calls them “Kurties”)––all in hopes of climbing the social media ladder. What he finds at the top is the basis for Eugene Kotlyarenko’s Spree, an equal parts terrifying, thrilling, and satirical look at how social media can warp the mind. – Josh E. (full review)

Survival Skills (Quinn Armstrong)

You’ve never seen a film quite like Survival Skills, an exploration of the police’s relationship to domestic abuse, told as if it’s a lost VHS police-training video from the 1980s. Director Quinn Armstrong brilliantly balances comedic absurdity and the very real weight of the issues he’s exploring. The script, partly inspired by Armstrong’s experiences working in domestic-violence shelters, is at turns funny, challenging, and amusing. – Orla S.

To the Ends of the Earth (Kiyoshi Kurosawa)

In a year defined by so many empty nights consumed by screens and worry, Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s latest masterpiece about coping with anxiety and depression is so affecting. He utilizes his history as one of horror cinema’s most accomplished masters to cultivate such tension from being lost in a new place, surrounded by too many strangers and unsure if you’ll make your next bus ride. However, instead of lingering in melancholy for eternity, Kurosawa provides eventual hope and unbelievable catharsis after an emotional journey. – Logan K.

To the Stars (Martha Stephens)

If today’s political landscape is any indication, much of the world is living in a conservative past, seething with disgust for another perspective they fail to empathize with, and emboldened by leadership that encourages such viewpoints. In her striking new drama To the Stars, Martha Stephens takes a character-focused look at such a small-town community full of repression, but rather than setting it in the present day, we’re placed in 1960s Oklahoma, a decision that speaks volumes for the ways we have and haven’t evolved as a country. – Jordan R. (full review)

The Twentieth Century (Matthew Rankin)

Look out: we have a new entry in the “Great Man” biopic subgenre, one that has spawned films as varied as John Ford’s The Long Gray Line and, uh, Jay Roach’s Trumbo. Joining the ranks is Matthew Rankin’s The Twentieth Century, which, with great aplomb, takes the piss out of Canadian history, showing us The (gradual) Taking of Power By William Lyon Mackenzie King, this nation’s 10th Prime Minister. – Ethan V. (full review)

Zombi Child (Bertrand Bonello)

Certain corners consider Bonello a major figure, rightfully noting his mixture of exacting formalism with provocative, borderline tasteless material—but if it’s that uncompromising vision or merely a matter of tough marketplace, his reach rarely goes far. Zombi Child‘s an equal-parts mixture of baffling and invigorating, ostensibly a study of colonial violence that’s also, if you want to look at it straight-faced, ultimately about a teenage girl who invokes ancient rituals after her boyfriend dumps her via text. Few movies this year were such a pleasure to swim in. – Nick N.

Continue reading: The Film Stage’s Top 50 Films of 2020