“Cinema is a never-ending long take,” Pier Paolo Pasolini once said. “And death is a form of instant editing of a whole life, picking and arranging our most significant moments.” There’s a lot of cinema and one devastating death in Abel Ferrara’s Pasolini, but instead of a series of “most significant moments,” this unconventional biopic limits its scope to the last day in the life of a writer, poet, director, and leading intellectual voice in Italy’s post-war era.

Before being beaten and run over with his own car on the beach of Ostia’s Idroscalo, Pasolini was busy with the release of his last film, Salò, giving prophetic interviews (even suggesting the now-famous title “We are all in danger”), working on Petrolio (an experimental novel) and Porno-Teo-Kolossal (the film he was writing at the time). While the intellectual is only hinted at, Ferrara recreates these moments by looking for the man himself, especially in the key relationships with his mother (Adriana Asti) and actor-friend Ninetto Davoli (Riccardo Scamarcio). It’s an absorbing portrait, particularly compelling when relying on Pasolini’s own words, which we hear verbatim through original letters and interviews.

Such is the complexity of Pasolini’s character that tackling him head-on seems a futile endeavor. There are a million ways to portray him more thoroughly, with more respect, and better understanding of his supremely nuanced body of work. This is why Ferrara makes such a good match here: at his best, he can zoom in close, let a few screws loose, and give the thing a good shake without wrecking the whole film. He has the blasphemous, simplistic audacity to dramatize some of Pasolini’s unfinished materials and use their oblique appeal to balance the more intimate, introspective bits.

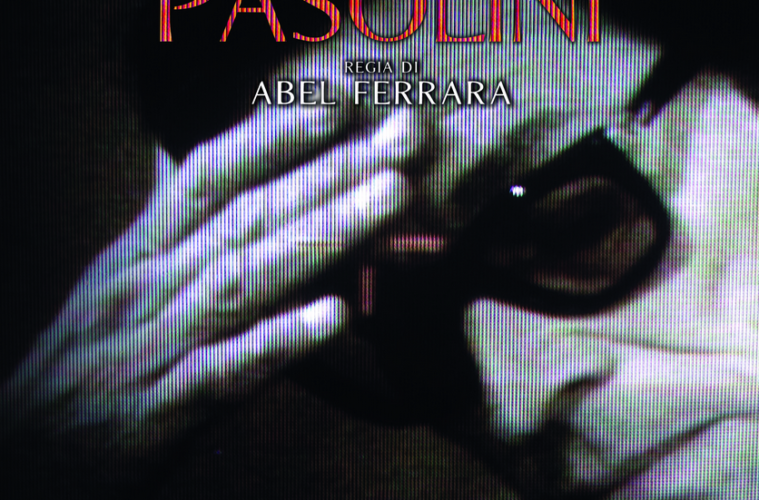

Comfortable in darkness, Ferrara’s glimpses of Rome are rendered in a mournful chiaroscuro, a succession of pitch-black, nocturnal blots to carve faces in. There’s foreboding sorrow in Pasolini’s eyes, disappearing and reappearing from a newspaper article about the latest murder in those “years of lead.” (It’s the last day on Earth indeed, and it’s going to be over before 4:44.) The only respite is offered by family life, with mother Susanna bringing light to her son’s room and to the film’s few bright scenes.

Not since 2005’s Mary has Ferrara dealt with such a high-stakes subject matter and plunged so deeply into it. Pasolini once described fascist architecture as partly metaphysical and partly realistic (incidentally, fascist architecture is used as visual metaphor at the film’s climax, itself perhaps an ill-judged aesthetic choice or a bit of supreme irony), and it’s a good description of Ferrara’s tone as well. You can tell he feels an affinity for Pasolini, which — however bizarre — gives him the confidence to do odd things, such as trying to make visual sense of Petrolio‘s enigmatic pages or attempt a weird mix of Italian and English for the dialogue. Is there a reason for it? Of course not. But it gives the film an offbeat, porous quality that Pasolini himself could have appreciated.

It was pretty much impossible for Willem Dafoe not to play this role, given his familiarity with the director and his knowledge of Italian culture, on top of a remarkable resemblance to Pasolini. He, too, seems to have approached the character in the least-literal way possible — it’s certainly not one of those precise, composed impersonations (not that it would fit in a film like this). Rather, his Pasolini is an approximation made of a thousand mirror reflections.

Pasolini premiered at Venice and will be released on May 10, 2019.