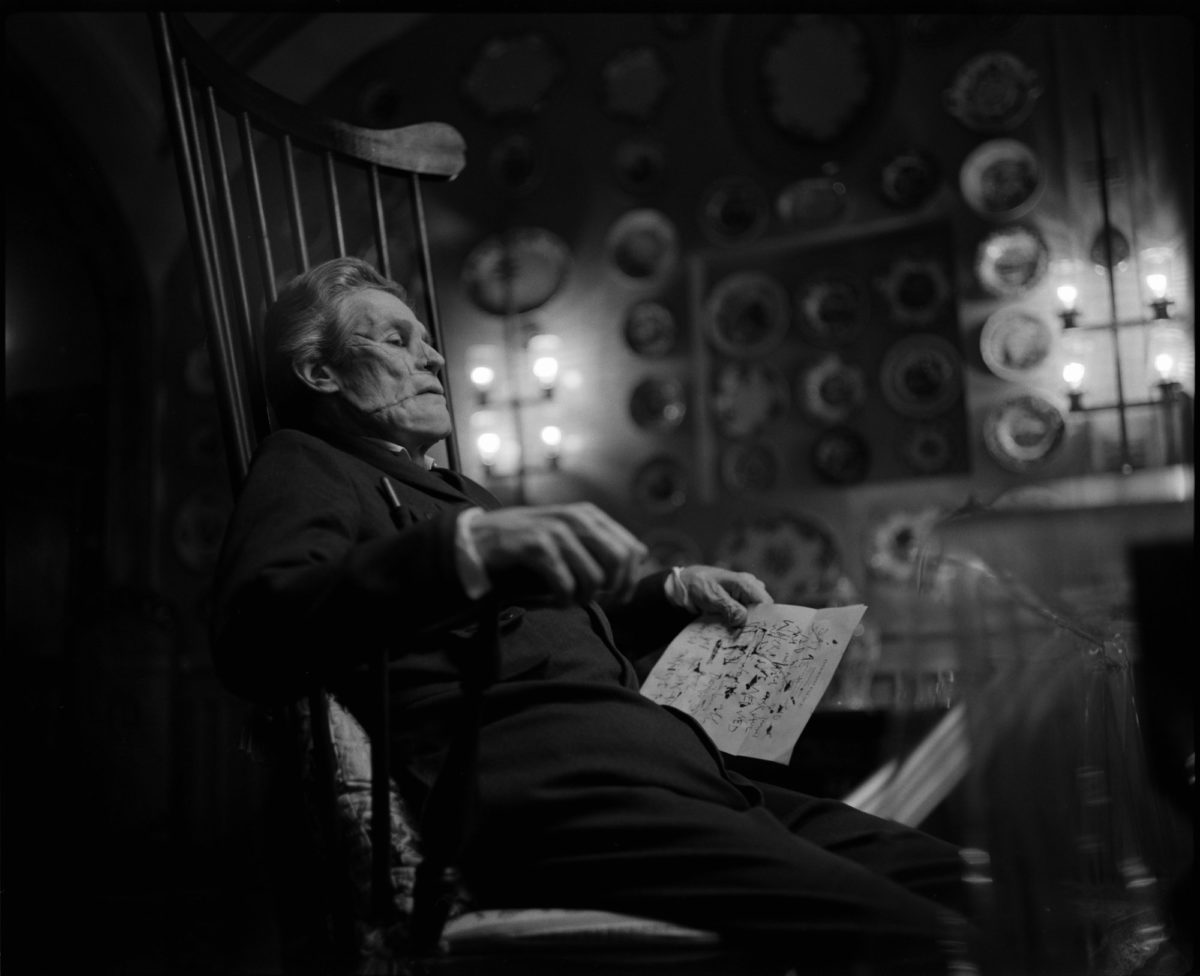

Willem Dafoe is your favorite actor’s favorite actor. He’s your favorite director’s favorite actor. He’s likely most people’s dad’s favorite actor. Over his 40-year career, the 68-year-old has become synonymous with character acting. If anything, he’s more known for his supporting roles than his leading ones. The actor dabbles in auteur fare, superhero blockbusters, foreign films, and any other meaty role he can get his hands on. With four Academy Award nominations and more likely to come, the actor had seven films debut in 2023. He continues to work in all genres, including voice work for animation. Dafoe’s acting feels somehow both unique and chameleon-like, shifting into different roles yet keeping a distinctive persona.

Though he has longstanding relationships with several directors, he’s never worked with Yorgos Lanthimos until Poor Things, his newest Frankenstein-esque Victorian tale. In Lanthimos’ latest, Dafoe plays Dr. Godwin Baxter, a mad scientist of sorts. Facially deformed without several major organs, Baxter grew up as a test subject for his father, following in those footsteps into a career of varying experiments. He plays the role of father, friend, mentor, teacher, and guardian to Bella Baxter (Emma Stone), the woman he created through an unlikely-to-work procedure.

In the fantastical comedy, Dafoe remains steady, a calming force, a God-like figure who’s literally called “God” by his creation. The actor gives another signature performance, soaking up dialogue and speaking it with such measured intellect and intensity. He exits the film for long stretches, only to return in moments of heightened emotion, providing a reason for Bella to return home and to her past. He becomes one of the film’s emotional throughlines, from reservation to acceptance to love.

With Poor Things now in limited release and expanding wide in the coming weeks, I chatted with Dafoe about cultivating a relationship with Stone, Gothic characters, and doing his best never to judge his characters, only see them as they are.

The Film Stage: I’m curious about Dr. Baxter’s relationship to fatherhood, from his very interesting, still-loving view of his own father––who operated on him––and then his own form of becoming a father by creating Bella. Where do you think he lands on the idea of fatherhood?

Willem Dafoe: It’s complicated because what you say is not untrue, but there are special situations. He’s willed himself to appreciate his father, because his father really did him wrong, and his father used him as a guinea pig, basically. And he accepts that, somehow, because he’s a believer in science. He’s very much a product of the Victorian age.

It’s about moving forward. The Industrial Revolution has happened and that’s a huge leap. And then we want to progress even further in science. He turns what is not a very pleasant situation into a dedicated passion to science and really cultivates an objective view of relationships in the world. Initially, when he reanimated this woman, it’s science, but he does have a beating heart and he falls in love with her. Not in a traditional father aspect, I don’t think, but he is caring and I think he sees in her the hope of a future and attaches himself to that. He’s given himself a new hope.

He’s also given her a new hope because this is a woman that committed suicide. So getting a second chance, I guess you could say, the way that parents live through their children. And then there’s a slight… it’s a little more juicy than that because he identifies with her somehow. It’s interesting to see how he tries to deal with her development. He tries to hold her, and then ultimately he realizes he can’t and chooses the higher love and lets it go and suffers terribly for it. But he punishes himself and says he’s upset with himself because he allowed himself to get involved. So there’s lots of interesting conflicts. He’s God. It’s a little more complicated than a simple father relationship.

And where do you fall in the morality of Dr. Baxter? With the reanimation and then the holding of Bella?

You try to get behind them and see the logic and the sense of it and make it truthful. Not just an empty gesture, but it comes from somewhere. So my hat is not in judging the morality. And I think he’s a little blinded to it. He doesn’t judge it any more than he judges his father for experimenting on him, which is pretty kooky when you think about it. But that’s also his generous spirit. And listen: like I say, I think he tries to do a good thing. He’s trying to advance, give her a life, give himself a life, and unlock the mysteries that science holds. So these are all things that aren’t for his pleasure. They aren’t for his career ambitions.

It’s pure science. He’s trying to dedicate himself to a better understanding. And that is a parallel to what’s going on with Bella. As before she leaves, even though he holds it quite tightly, he’s also teaching her how to see, and you can see his delight in watching her discover things. He socializes her. He gives her social conditioning only to a certain point. But you see he gets a pleasure at watching his experiment unfold.

You mentioned that she calls him God, and I’d love to know what that feels like on set, as an actor, being called God every day. I know you’ve played other notable religious characters in the past, and was interested to hear if that had any specific effect on you.

I thought it was strange––like it pokes out of the story a little bit––but I accept it and just take it. One of the things that was really helpful was looking at videos of the writer that wrote the novel, because I think he put a lot of himself in this character. I only know him from these videos, but he had a devilish sense, a perverse humor, and then sometimes very obvious humor. And so I give him a pass on the God business.

That’s fair. How did you come up with the tone of Dr. Baxter, this scientist? Especially with more outwardly comical performances and characters around you. How do you balance that tone?

You play the actions, you see what has to happen. He’s a product: he lives by a Victorian social code and he’s a scientist. He’s not there for society by the nature of his past––I think he’s been a little alienated from society––and basically, other than being a teacher, he’s dedicated to his little domain, his laboratory. That’s his work, that’s his life. So that’s what I’m concentrating on, where a lot of the other characters are mapped out making their way in the world. I’m a little bit retreating from the world and going into my world of science. So he’s more reserved. He’s living more in solitude and he has greater power in his life. He’s got a good setup where he is.

Thinking of the other characters––Max McCandles is basically a student. Duncan Wedderburn is ruled by his you-know-what. And, you know, we can go on and on and on. These are people that are struggling to find their way a little bit.

You think his purpose feels much sturdier?

I do.

You said earlier that it’s not as simple as a normal father-daughter relationship. How did you cultivate that relationship with Emma?

You can’t help but love her! You know, listen: you can lay down in a bed with Emma acting like a child, read a bedtime story, and it doesn’t take a lot of acting! I mean, I’m not trying to be cute, but I’m trying to get to the point, you know? It was beautiful like that.

There’s something half-sentimental and half-really-tough when she says, “Stay with me. Sleep with me.” It’s innocent enough, but on the cusp of not-so-innocent. He probably would like to, but he now has a struggle there. That’s interesting to me. I don’t know, when you get to a certain age, there’s something in younger people that you’re attracted to because you see a possible future. And for me, in young women, you project an imagination about what could happen with them, where they could go. And that’s a very powerful feeling. I know that from my life. I think Godwin Baxter has that a little bit. And in fact, it comes up when, basically, he’s pleased to give her his practice. He’s passing the baton very happily, as he’s about to leave us. It’s not just a joke when I say that it’s easy to have the character be in love with Emma, because you love her when you’re performing with her.

It’s both a nice sentiment and it does make sense. It’s both.

It roots it in my experience, and with a little abstraction it becomes Godwin’s experience.

In the last five years or so, you’ve taken more and more roles in these Gothic films, often with auteur filmmakers. Is there something specific in these Gothic characters that draws you to them?

I don’t make the connection, but I think you’re onto something. I’m not that aware of it. All I can say is: I’m naturally drawn to things that are a little elevated. I come from the theater. I think it helps to have a coded language, something that’s not totally dependent on a naturalist style of acting. I think we can go deeper and we can wander more, we can dream more, we can imagine more when we’re taken away from that as a measure of reality. We create a world that is not one that depends on its validity.

Our experience day to day is lifted out. It helps us question. It helps us wonder. It helps us. There’s always exceptions, but I like things that are rooted in spirit, but elevated and far from us in actual texture and look and style. Because it takes us away from assumed truths; we take it away from naturalism.

And we have to enter the world and get into Bella’s Head. “What is this? What is that? How do I feel? Does that match my experience? It doesn’t. Maybe I’m deluded in my experience. I didn’t realize that.” You know, this kind of thing. I think that’s the pleasure for me. When I’m watching a movie, this whole getting-knocked-around, it’s the best thing. That’s why movies aren’t just entertainment. They can be real food for your life.

Poor Things is now in limited release and expands wide on December 22.