The mark of an actor’s career, I think, is what extent their filmography can reflect the time they’re working. Matthew Modine is a prime case: we can point, first and most easily, to leading a Stanley Kubrick film, a title for which there are fewer living holders than men who’ve walked on the moon; there’s one of the all-time biggest box-office disasters (one he’ll gladly, valiantly defend); supporting roles for Christopher Nolan, Robert Altman, Oliver Stone; and aiding auteurs Abel Ferrara and Alan Rudolph as a star. (There’s also the factor of what iconic movies he not only didn’t appear in, but turned down.) This makes especially appreciable the Roxy Cinema’s retrospective The Many Faces of Matthew Modine, running Friday through Sunday with five films: Ferrara’s The Blackout, Rudolph’s Equinox, Cutthroat Island, Birdy, and his own feature If… Dog… Rabbit…

Having long admired Modine’s screen presence, I was happy to speak with him about this retrospective. But it engendered a longer, deeper conversation about the places actors go for their craft––the process, its rewards, its collateral damage, and the unique opportunity to reach people.

The Film Stage: Tonight I’m seeing The Blackout, which is kind of a personal favorite––as much as a film that brutal can, you know, be a favorite.

Matthew Modine: Yeah. It’s a very uncomfortable movie for me.

For you personally?

Yeah.

May I ask why?

Well, the entirety of the film. It was the first time that I had worked with Abel. We’ve become very good friends, you know, subsequently. I mean, the brutality the subject matter of the story, it… you know what it is? Your body doesn’t know it’s acting, so when you put yourself through trauma––though you know that you’re memorizing lines and that you’re acting for a camera and you’re acting with another actor––the trauma that you put your body through, your heart rate goes up, your respiration goes up, your adrenaline goes up.

All of the physical things, if you’re doing the job and emotionally connected to the character, are going to have an impact on your body and who you are. And you know Abel was, is––was and is––a very demanding director, and so it was a very different experience from every kind of film that I’d made up to that point. You know, subsequently, we did Mary together. And… what was it called?

Go Go Tales.

Yeah. Yeah.

I also love your introduction in Mulberry Street, when you pull up on––I believe––a Segway.

Was that videotaped?

Yeah. You pull up on a Segway and kind of point at the camera in recognition, and I think a little card comes up that says “Matthew Modine.” The first time I saw that movie, which I love, I just burst out laughing.

Oh, my God. I’ve never seen Mulberry Street.

Oh, it’s great.

But that’s interesting. It was a Segway, and that was obviously before all the e-bikes and electric scooters. And I thought, “Maybe the Segway is a great way for New Yorkers to get around town.” [Laughs] And I took the Segway to the New York Film Academy and said, “You know what? This is the coolest Steadicam device ever. If we can just figure out how to mount a Steadicam on this, tracking shots, all these things…” And I was a real visionary for Segway––talking to the city and trying to get them to be a part of moving around New York City. And the problem is: you just look so stupid on a Segway. Nobody looks cool on a Segway. [Laughs] Oh, my God. I forgot about that.

They’ve become a real relic.

But they use them. People use them all the time on film sets, for doing Steadicam shots––for doing exactly what I was saying. And Jerry Sherlock––he’s passed away now––when I told him about using the Segway as a, you know, Steadicam, doing tracking shots, he thought I was crazy. Because they go about 20, 25 miles an hour, and they’re really stable.

The Blackout

I remember, in the early 2000s, those being very much touted as a new form of transportation. But now it feels perfect that Mulberry Street, such a capture of a specific moment in time, has it.

[Laughs] Yeah, you should have heard Abel talk about it. He thought it was the stupidest thing in the world, the Segway. Hold on––I’m going to make a cup of coffee while we’re talking.

I have to wonder how much of a personal hand you had in choosing these films that the Roxy is showing, and how much they were presented to you as options.

The only film that I ask that they include was the film that I wrote and directed, If… Dog… Rabbit… It’s an extraordinary story about a whole bunch of things. It’s about my life, about how I might have ended up had I stayed in Imperial Beach, California––where the film is supposed to take place––in Tijuana, where I grew up, spent so much time surfing and, you know, debauched weekends drinking tequila. It was an easy place to go and do criminal activity, Tijuana. At that time it was pretty rough-and-tumble, and now I think that Tijuana might be the second-largest city in Mexico. It’s huge. But yeah: it was a lot of drugs and alcohol and criminal behavior that I sort of saw.

Aldous Huxley, in his book Doors of Perception, talks about life as kind of this long hallway with lots of doors. And in our lives, as we’re walking down that hallway––which we could call “life”––we enter different rooms. We can open the door and look in and go, “No, no, no––that room’s not for me. Oh, this is kind of interesting.” And we go in and we experience it for a little while and say, “Okay, I’m done with that. Let’s continue on down the hallway and see what lies ahead.” And I saw that if I would have stayed in Imperial Beach, California, that my future wouldn’t be, obviously, what it is. And so I ran away from home and went as far away from Imperial Beach as I could.

It almost feels like one corner of the United States, because it’s the most southwesterly city in America––right in the corner––and came to New York to pursue this profession. But yeah: the movie is called If… Dog… Rabbit…. It means, “If the dog didn’t stop to take a shit, he would have caught the rabbit.” “If” doesn’t count in our lives. There should be no “would have, could have, or should have.” There’s just “done.” You know?

And that’s that’s the way it is: you can live your life and regret what you would have done or what you could have done, but what’s important is what you did. And so that’s what I did: I got out. I got out and I moved to New York. So it’s a very personal film to me about that. It’s a struggle, a personal struggle of trying to understand death––that we live and then we die, and what is death and betrayal? But the most personal film because of who I am. My father was a drive-in theater manager and I grew up with drive-in movies. So what I wanted to make was to take these kind-of-subversive ideas of death and, you know, escaping and running away––trying to get away from your past––and then disguise it in a drive-in movie. Which are generally very simplistic plots, with a problem and a dilemma and a solution.

So I tried to take all that and create this kind of subversive drive-in theater movie. I think it’s a really good movie.

No, I would like to see it this weekend. Knowing your connection ups the interest for me significantly.

I wrote and directed it. You saw who’s in it? Julie Newmar, who was the original Catwoman. I mean, all these people really loved the script. Bruce Dern. John Hurt. Kevin J. O’Connor, who was in There Will Be Blood––he was the one that was pretending to be Daniel Day-Lewis’ brother.

And he’s in Equinox, which they’re also showing.

He is in Equinox!

In that movie he has what I consider the strangest food order in the history of cinema. Do you remember what it is?

I don’t.

He orders spaghetti and meatballs with root beer “with just a little bit of ice.”

[Laughs]

How much do you see this series as representing your career? Because you have Birdy, which is among your first five or six films; there’s The Blackout, which began a really amazing partnership with Abel Ferrara; Cutthroat Island, a movie people know more for its post-release than the film itself; If… Dog… Rabbit…., which you’ve just talked about so passionately; and then Equinox, which is maybe an anomaly because you haven’t worked with Alan Rudolph otherwise, but also is quite an exercise for you. And then this new short, I Am What You Imagine, playing before everything.

Well, I only picked one. I think it was important to play Cutthroat Island, because it’s interesting that Quentin Tarantino thinks it’s one of the best action movies ever made. The Duffer Brothers, who did Stranger Things, think it’s definitely one of the best pirate movies that’s ever been made; it’s one of their favorite movies, and they want to make a pirate movie. And it’s interesting that we made that film, and then shortly thereafter, Pirates of the Caribbean came out––which was a bizarrely fantastically successful, financially successful franchise.

Cutthroat Island, when you see me hanging from a 300-foot cliff, I’m really hanging from a 300-foot cliff. When we blow up a pirate ship, it’s a real pirate ship; it’s not a little model. And I think that what’s exciting today is that, when you watch the film, you realize that it’s not CGI effects. You know, it’s not a Marvel movie. It’s epic and it’s huge.

Cutthroat Island

All of that money, that’s all people seem to talk about––the $100 million that it cost to make the film. Every penny of it is on the screen. And it was so loudly criticized. It was really the first film in my career that was badly reviewed. I mean, really viciously attacked. Something that had nothing to do with me, but one of the things that I think was crippling for the film was: the audiences just weren’t ready for an action movie with a woman, you know, helming the film. And that’s interesting to me. It’s why we have Lynda Carter doing the Q&A, because it’s a question about Hollywood.

You know, you hear people say, “We’re looking for strong women roles. There’s never been strong roles for women.” And it’s like: do you know the history of Hollywood? Have you ever heard of Katharine Hepburn? Have you ever heard of Rita Hayworth? I mean, even Marilyn Monroe––who some people might dismiss as a dumb blonde––is one of the smartest actresses, maybe, in the history of the motion-picture industry. She played it brilliantly. But she was nobody’s fool. Betty Davis. All the way back to the silent era with Mary Pickford. She really invented the concept of residuals, and had a studio with her husband.

United Artists.

Thank you. Yeah. Something happened along the way where that mantle was taken away from women. I think it’s coming back. When you see the Academy Awards and you look at the roles that women get nominated versus the roles that men get nominated, I think that the five women that get nominated, generally, have much better roles [Laughs] than the five men that get nominated. They’re much more layered and impactful. But the thing is: it’s going to be interesting to have that discussion about Cutthroat Island with Lynda Carter.

It sounds like it was a difficult experience to make a film and then have it be so badly reviewed.

Well, when we were making it, of course, the reviews hadn’t happened. There were people that were critical of the film before we even started filming in Malta. And by the time we got to Thailand, we knew that the studio, Carolco, was in trouble. But, you know, the movie that escapes the criticism––I don’t know how it was reviewed; I don’t really read reviews––was Showgirls. That was also Carolco and also, like, a $100 million film. If you look at those two films and say “which is a better film” and looking at a film just purely for production cost––I mean, you can see it’s justifiable with Cutthroat, and it doesn’t make any sense that Showgirls would cost that much money.

This is what I know: I’ve done over 100 films. I’ve made about 15. Like that studio executive said, “Nobody knows nothing.” We’re all given the same equipment––a camera and lenses and sound departments and production designers––and you put together this team of people and everybody is passionate about doing a great job. You come together and you work together and you put this film together, and sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t. And what I haven’t been able to figure out is: why does it work sometimes, and why does it not work other times? Really successful, talented people who came together to make something and it didn’t work.

There’s a restaurant in New York City––I don’t know if you’ve ever been to it––called Joe Allen.

I haven’t.

It’s a famous eatery, watering hole for actors after shows. You know, when you finish a show, go to have dinner at Joe Allen, and inside the big room he has posters up of plays that opened and closed––one night, maybe five nights.

Got it.

And I used to think, when I was a young actor, he was kind of making a joke about, like, “Look at these plays that opened and closed in one night.” And as I got older, I realized that what Joe Allen was doing was celebrating those plays that opened and the effort that went into… it’s really hard to do a play. I mean, it’s really hard to make a successful play. And so what he was doing was celebrating and saying, “Look. Look at all the talented people that came together to make this production, and it closed after one night.” It was to celebrate those people. So as I say: I don’t know why something is successful and why something isn’t.

So the lesson that you learn from that––that you must take away from that––is that the most important thing, the most important responsibility, that I have as a performer or as director or as a writer is to do the very best that I can. To show up, to know my lines, to be prepared, and do the very best I can. Because you just don’t know when it’s going to work and when it’s not.

Are you especially fond of the movies that are showing in the series?

I think it’s a terrific… I love Equinox. There’s an element of it that I wish that he would have edited it out, that he didn’t. But, you know, he’s the director and it’s his choice. But it didn’t prevent the film from being critically successful. I think it got pretty good reviews and it got nominated for an Independent Spirit Award. He, Alan Rudolph, got nominated; Lara Flynn Boyle got nominated; I got nominated. So it wasn’t not-appreciated, but I just think it was a difficult piece of art that people didn’t understand.

This may sound like an extreme––just because I can’t think of a different painter––but like Van Gogh not being able to sell a painting in his lifetime, and not being understood or appreciated. You know, that’s not uncommon. I think Equinox is a wonderful, unusual, different kind of film for people that are looking for something different and off-the-beaten-path. It’s very enjoyable.

Equinox

The Quad Cinema, here in New York, did a big Alan Rudolph retrospective about five or six years ago; a lot of people came out. Part of what made them compelling is that––and I hope the same thing happens this weekend––is that the movies weren’t necessarily so well-known, but there is this feeling of, “These are probably worth seeing.” It’s what you’re saying about that retrospective appreciation films can have.

What were the Alan Rudolph ones? Obviously Choose Me.

They played all of them.

They played Equinox?

Yeah. You also have this short film, I Am What You Imagine, which is very vaguely described as “a sensual exploration of the unexplainable.”

I’m not sure who to give credit to, but because it’s playing the festival circuit right now they thought that it was important to share. I mean, I think that because somebody who’s familiar with my short films felt that it was the best one. And I don’t agree––I don’t think it’s my best short film––but I think it’s a very important message for the world right now. If I completed the title for you, it might be illuminating and take the vagueness away from the description. It’s I Am What You Imagine Is Love.

I began talking to you about If… Dog… Rabbit… and trying to understand death and existence and, you know, walking down one of these long hallways. But there’s an earlier film that I made called Ecce pirate, which is also about that: trying to understand. I didn’t understand it until I was editing and my father passed away; I realized that that’s what was really behind the story. It was trying to come to terms with and trying to understand that. At the end of If… Dog… Rabbit… it’s not death, but it is a different kind of death. In the end, we’re all alone. Right?

Of course.

We’re there, on the pillow, looking back at our lives and trying to, I imagine, understand this––this moment of transition from this animate object to something inanimate, and what that might be. But what I would hope is that, having seen a few people transition, I don’t go out desperately trying to have another breath. But say “ah” and exhale and leave––I’ve done enough; I’ve enjoyed myself––and move on. I think it was Godard who said we make the same films over and over. I’m not getting the quote right, but you know which one I’m talking about.

I think many filmmakers have said some variant of that, which is very telling.

The thing that’s nice about I Am What You Imagine––I feel like I’ve answered that question. He says, “What is behind our heart’s desire to beat? What is behind our lungs’ desire to take air?” You know, that we do these things voluntarily. When we stumble and fall, we put our hands out to protect our bodies. So there’s something behind that. And included in that is the desire to, hopefully, ease suffering, to reduce pain and other people, to be compassionate, to be forgiving. Because that’s what’s behind this message of the film––of this idea. I shouldn’t say “message.” The idea of the film in a time where, you know, there seems to be a lack of compassion and a lack of humanity; I think that it’s an important thing to hear.

I’ll be seeing it tomorrow in front of The Blackout. So I imagine those two will contrast.

[Laughs] A little bit.

I saw The Blackout when they did a big Ferrara retrospective at MoMA about five years ago. I love the movie but felt genuinely embarrassed sitting in a room with other people watching it. I was like, “I need to watch this alone,” with nobody else.

You mentioned Birdy really briefly. Birdy was probably one of the most important films of my career. I mean, people often talk about Full Metal Jacket, and it’s because Stanley Kubrick is so celebrated.

Of course, yes.

But, you know, something that Kubrick said to me was that films should be like important pieces of music. It’s something that you can listen to over and over and over again, and each time you go back in and hear it, that you hear something different––that you hear a chord progression that you didn’t hear before, that you hear something sympathetic or emotional that you never heard before. Because you’re a different person. Every day, when you wake up, you’re a little bit different than you were yesterday. And so that that journey––the emotional and physical journey that we go through in living our lives––we should be able to go back and look at a film and have a different experience with it. I mean, that’s something that Kubrick understood and I believe did better than anybody else.

So many of these films were dismissed when they were released. The Shining wasn’t looked-upon as a good horror film. 2001: A Space Odyssey was dismissed. Barry Lyndon was dismissed. And they’ve all become classics, you know? The reason I mention that is because I think that Alan Parker is one of the most important directors of his generation. If you look at his résumé––from Bugsy Malone to Midnight Express, Angel Heart, Fame, which is so much fun; even Evita––he’s just an incredibly talented and underappreciated filmmaker, I think, of his generation.

It doesn’t play much.

It was a huge film outside of the United States, and I think that was because they were honest with the advertising of the film. Birdy was made before there was the expression “post-traumatic stress”. And in the book it takes place during World War Two. I think they use the term “shell-shocked.” Today we would say “post-traumatic stress,” and there’s a lot of people who think that Birdy and Al are the same person living, you know, sort of schizophrenic––that they’re really the same person, which is interesting. They tried to sell it like it was, you know, two crazy kids from Philadelphia. The poster was me flying and Nic at the garbage dump, where I jump off the bicycle and fly. In Europe and in Asia, they put me naked, sitting on the edge of the bed––which eventually became the poster for the film––but they sold it for what it was: a dark story about these two broken people.

The film was a huge success; it won the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival. I mean, it played in theaters in Paris, in the Champs-Elysées, for two years. They contacted me and asked if they could use my image to sell some, like, Prozac or something––some antidepressant drug in France––and which I said no to. When we went to Japan, you know, people would come up and embrace me as if I was Birdy. What they were really wanting was not to comfort me, but they were so grateful that there was a film that was telling a story about them––about the trauma that individuals are suffering all over the world.

Suddenly there was a film that was empathetic to those people that wasn’t a superhero movie or, you know, good triumphing over evil and beating it down. It was a film for people that… have you ever been to a Comic-Con?

I have, yeah.

I’ve been to several of them. But what’s wonderful about the Comic-Con is that there’s a whole world of people that are not like the people that we see in movies. Sort of misfits and people that seem to be kind of ignored. And it’s a place where they go, and they get the opportunity to dress up in cosplay, and I think it’s so beautiful. It’s such a pleasure to go. I mean, the last one that I went to was in Liverpool, and the people were so grateful––because they thought that everybody must live in Hollywood, and I’ve come all the way from Hollywood to Liverpool to see them. That I had gone to see them and their lives mattered.

Because what I don’t want to do is make that feel transactional, that I get paid to go there––which I did. But it’s so much more important than that, what’s happening. When you meet somebody who thinks that is such a kind of deeply spiritual, profoundly humbling moment; you must be very careful with them and respectful of them. It was extraordinary. It was an extraordinary thing for my wife and I both to experience. Especially in Liverpool.

Why especially Liverpool?

Because it was different than, you know, going to New York Comic-Con. It’s a little place, Liverpool. The most famous thing that came from there’s the Beatles. And Titanic. [Laughs]

Well, this weekend will be an opportunity to speak with people directly.

I hope so. I hope that you’re able to bring some people into the theater. I mean, it’s so important to me that the people know that Julie Newmar is in If… Dog… Rabbit… because she was the first Catwoman. And Lisa Marie, who was in Mars Attacks! and Sleepy Hollow, that she’s in the film and that she’s going to be there. I was hoping Kevin J. O’Connor would be able to make it out, but he’s in Chicago and he couldn’t. But Lynda Carter and Isaac Mizrahi, who loves Birdy, are going to be there to talk. I just hope that the theater’s full and that we have this really wonderful, shared experience in a movie theater.

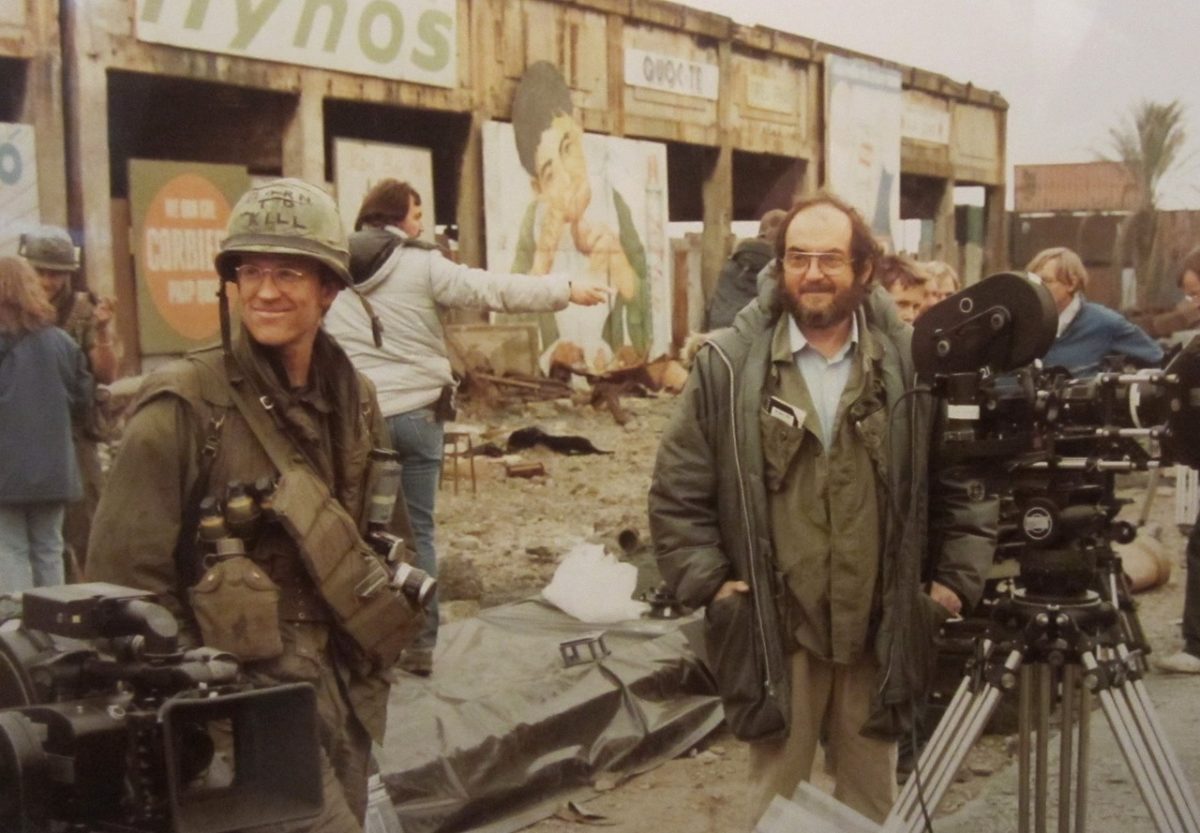

Behind the scenes of Full Metal Jacket

What was your relationship with Kubrick after Full Metal Jacket? The film came out in 1987, he dies in 1999, and a lot of the time in-between is spent developing movies like A.I. and Eyes Wide Shut.

Yeah, we stayed very close until he started production on Eyes Wide Shut. And once that began… I had been witness to, like, he and I’d be having a conversation, and somebody would come, but because he had incredible focus when he was speaking to you, he didn’t want disruption. So if we were having a conversation about something and somebody interrupted that moment, he could turn and just go like, “Yeah, what do you want?” And it was always really uncomfortable to me, to have somebody you’re speaking to turn to somebody and sort of dismiss them.

The last conversation I had with him, I called up and he said, “Yeah, Matthew, what do you want?” And I said, “I didn’t want anything. I was just calling to say hi, Stanley. Stanley, can I call you back? Because there’s someone at the door.” I got off the call because I didn’t want him to have to say, “I don’t have time to talk.” So I said, “Someone’s at the door. I’ll call him back,” and I never spoke to him again.

But it was out of respect for that focus that I knew was a requirement for him to be able to do his work. It was important that I not be a disruption, that I not be somebody who was interrupting the process of his next endeavor––you know, in working on Eyes Wide Shut. And the next phone call that I got regarding Stanley was from Michael Herr––who wrote probably the best book about Vietnam, Dispatches, and wrote the voiceover in Apocalypse Now, and he wrote the screenplay for Full Metal Jacket. He called to tell me that Stanley had passed away.

I see.

Up to that point––for a good decade––we were in touch all the time. His daughter moved to New York City, and he spoke a lot to my wife––as a father concerned about his daughter living in New York City and wanting to make sure that she was safe, that she was being looked after, and could she come over to the house for dinner. We did. We looked after our friend. But it wasn’t because of Stanley; it was because we really loved Vivian. I felt the responsibility when I was traveling around the world doing publicity for Full Metal Jacket. He said, “Remember that, when you’re speaking, you’re speaking on behalf of me.” I wrote about that at the end of my diary, Full Metal Jacket Diary, and I said, “How could I ever fill those shoes? Those are mighty big shoes to fill.”

The Many Faces of Matthew Modine takes place Dec. 1-3 at NYC’s Roxy Cinema with the actor in person.