Alejandro Amenábar’s historical epic Agora is high-minded and visually pleasing, but doesn’t quite pull itself to maintain an entertaining momentum. It has many of the hallmarks of an epic, from the swelling music, to the sweeping city views, to the main characters ability to meander through surrounding violence unscathed, but the pace is often stalled by wordy monologues and the need to impart information, causing a loss of emotional impact. What we are left with is a story about religious intolerance and the resulting powerlessness of reason.

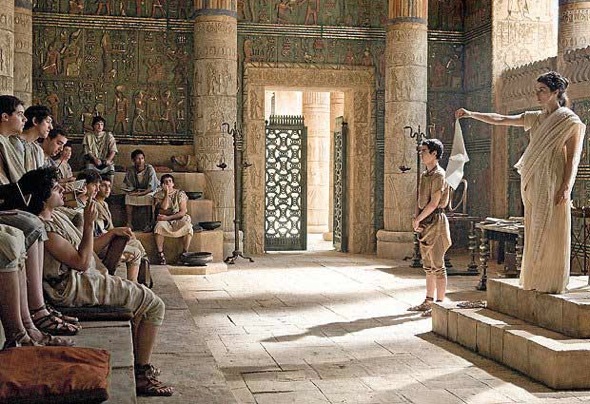

The story begins in 369AD, when tensions between polytheistic Pagans and Jesus-worshipping Christians have been escalating. At this time, we meet Hypatia (Rachel Weisz), the fourth century AD philosopher who lives within the legendary Library of Alexandria, who teaches both pagan and Christian students theories of astronomy. It is within this classroom that we meet the two men who are in love with her: her slave, Davus (Max Minghella), and her student, Orestes (Oscar Isaac).

This academic tranquility is shattered when Pagan leaders incite an attack on the Christians as they gather in the marketplace, thinking the Christians are no match for them. They quickly discover that they are sorely mistaken, as the Christians retaliate in great numbers, forcing the Pagans to barricade themselves into the library compound. When the openly Christian Roman emperor Valentinian decrees that the pagans must surrender the Library to the Christians as punishment for their attack, Hypatia is forced to flee with Orestes, knowing that the contents of her beloved library will be destroyed. Davus, having been inspired by the tenets of Christianity, stays behind.

At this moment in the film, the camera pulls away for a space view of the earth, and then re-approaches Alexandria several years in the future. This gap of time feels almost like an intermission, dividing the film into two separate feeling parts. At this point in the story, we discover that Orestes has renounced paganism and converted to Christianity to aid his rise in Roman politics, and is now serving as the prefect of the region. Davus has joined a Christian militia called the Parabolani, having shed his slave status. Hypatia has continued to live in Alexandria, pursuing her astronomical research and trying to understand the earth’s relationship to the sun.

It is not, however, a peaceful time, as the Christians begin to wage war on the Jewish population of Alexandria. As tensions again begin to mount, Hypatia finds herself to be the Christians’ next target, condemning her open atheism and devotion to science rather than religion. It is at this moment that both Davus and Orestes must choose between their church and the woman they love.

One can hardly blame Amenábar’s frequent sweeping shots of the city; the production design is superb, bringing historical Egypt to life in great detail. It actually heightens the emotional impact of a number of moments, particularly the painful moment we see the library, the greatest repository of human learning, trashed by the vengeful mob. The slow-motion tracking shots give a great sense of gravity while maintaining a flow of action.

Weisz turns out an excellent performance, making it extremely difficult to imagine anyone else in this role. She gives Hypatia great levels of strength, beauty and intelligence that one would imagine the real philosopher having.

However, despite strong acting performances couldn’t make up for the missed emotional connections. In focusing on the struggle between science and ideology, the an unconsummated love triangle fizzles with little passion. Amenábar has proved himself to be a talented director in his past work (The Sea Inside, The Others), but this being his first film of such a grand scale, I feel that his characters and subtleties are lost to another agenda.

In terms of the religion versus science debate, there is little question what side Amenábar is on, as while the story is based in history, the theme of Christian fundamentalism’s threat to scientific learning has a strong dominance throughout. Interestingly, the only principled character who doesn’t compromise their values is Hypatia, the only declared atheist. If I had to assign a moral to the story, it would the argument that we need science and reason to bring people together, as opposed to using theology to set them apart. Perhaps if some of this focus had been shifted towards developing the supporting characters, I would have found it a bit more captivating.

It’s a very ambitious film to visualize and was always going to be a difficult one to bring to the big screen, but I left wishing it had been made for the smaller screen. There is so much information being forced into the dialogue, that it becomes almost preachy at times, causing issues with pacing. Also, referring back to the intermission-like skip in the timeline, I feel like this story could have been better delivered in two parts, or as part of a mini-series. There’s just some much that is being forced into such a short span of time that much of it is not done justice, and the film ends up feeling much longer than it really is.

Agora had the potential to be a great film but winds up being somewhere slightly above average, and ends up feeling longer than its 126 minutes (15 shorter than its Cannes version). While I’d say it’s worth checking out, I wouldn’t recommend planning your weekend around this cinematic outing.

6.5 out of 10