It is rare that a film can approach the subject of war on a purely human level. Often, these films feel the need to comment upon and offer solutions to the larger political and social issues at hand, while failing to grasp or explore the human story that they purport to want to tell.

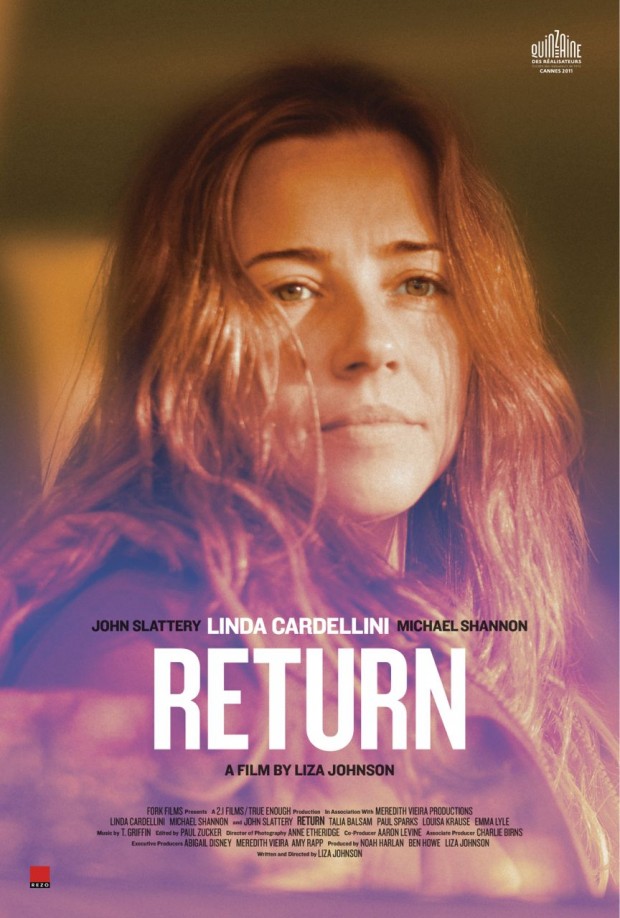

Director Liza Johnson, in her first feature film, managed to sidestep this potential pitfall and deliver a deeply personal story that asks the audience to consider the characters and their lives alone, while leaving the larger, impersonal questions surrounding the war on the sidelines. In doing so, she makes an affecting and powerful film, one that even those who have grown weary of war films can appreciate.

It was my great pleasure, then, to be able to speak with Johnson earlier this week regarding her film’s conception and creation; the unique merits of a female-led war drama; and the human toll that war, any war, takes on lives, relationships, and the concept of home.

___

The Film Stage: Diving right in: you both wrote and directed this film (Return), so personally, where did this movie come from? What was your inspiration and motivation to make this film?

The Film Stage: Diving right in: you both wrote and directed this film (Return), so personally, where did this movie come from? What was your inspiration and motivation to make this film?

Liza Johnson: I guess it came from two places. One was a conversation I had with a friend of mine who told me a story about what his efforts were like to try to stay married when he got back from his military deployment. And I feel like we like in a very separate culture where military and civilian culture doesn’t really intersect that much. So it’s true, if I were in the military I would have heard a story like this before, but as it was I… it felt very different for me to hear this kind of account of just being in his very everyday personal life and trying to, you know, cross across the gulf of experience that had opened up between him and his wife. To me that was really talking about the war on a different register than I was used to because I feel like most people in civilian culture talk about it kind of statistically, like “oh, 42 people died in a car bomb, blah blah blah,” you know, or in kind of policy terms like “pro this, con that,” you know, like that.

And so it felt like it was a story I maybe hadn’t heard enough of. So when, after I talked to him, I started thinking about this character, I’m not quite sure how I made the intuitive decision to make Kelli a female character, but once I did he (her friend) introduced me to a bunch of female soldiers and from them I met more people and so on. And it sort of led down this path of research which I think helped me t generate a very plausible character, and it also convinced me that I should just go down this fictional path because every person that I met was so different from each other that it sort of relieved me of the responsibility of trying to create a typical female soldier. Because I don’t think there’s a representative figure. So that conversation with him was a really big starting point.

I guess the second thing I would say is that I came from a town like the town in the film, you know, a kind of industrial river town that has lost its industrial base, and where people are kind of, like, really aspiring to put forward a future where even though there’s not a lot of meaningful work and kind of a big drug economy and I guess I’ve been… I don’t live there anymore but I’m kind of invested in that world. So I kind of put those things together to make this film.

You were saying how you were not approaching the story from a policy position, and there definitely was that feeling in the movie: you never mention exactly where Kelli has gone. I don’t think that Bud’s character said exactly where he was when he was deployed over there. Was that a very conscious decision to almost remove the real world context, to divorce it from a political reality and just turn it into a human story?

Kind of, yeah. In some ways we didn’t say where she had been deployed just because I had been working on that film for years, you know what I mean? I think I wrote it in 2008 and when I wrote it people were very interested in Iraq, but not Afghanistan. When we shot it people were very interested in Afghanistan and not so much interested in Iraq. And I guess in some ways that literal thing about not naming the place was more like an effort to just make the film felt and relevant even though we didn’t know what kind of historical context it would emerge into.

But yes, it’s not that I’m not interest in those policy questions, it’s just that I feel like that is covered well in other territories. You know what I mean? TV does a good job of that, I don’t think they need my help.

This is another in a seemingly increasing genre of films that do approach the question and realities of war from the point of view of people either left behind or returning home, rather than older films that would have taken the camera into the theater of war. There hasn’t really been a war film that’s gone over there in sort of the way that Tora Tora Tora or The Longest Day has, and part of me thought that the reason for that might be because these aren’t the kind of wars that are viewed in a “heroic” context anymore, and that there’s kind of a this attempt to divorce the violence and action, the kind of “thrill” of the War Film from the wars themselves.

That’s interesting to me. And I also don’t think it’s anti-heroic, I also feel that there’s war films that go into a theater of war and position the U.S. Soldiers as at odds in a way with their own mission. What I wanted to do was just not even enter into the territory of those kind of moral and policy questions because I feel like that our existing conversation about that seems to just have some limits, where people are like, “this is good” or “that’s bad” and I’m sure that at least one of them is right. But I feel like that to reiterate that doesn’t necessarily shift the conversation. Something that a movie can do is ask you to feel certain phenomena in a different way than you’re used to. That’s why I made that decision; it’s not because I don’t have opinions about policies or whatever, it’s just because I just am interested in the story feeling different than certain existing conversations.

You talk about the film being a different cut than other films that you’ve seen. Going into it, what was the most original, the biggest and newest idea that you felt that you wanted to express that had never really been said before? To that end, how effective do you think you were in actually making that happen?

For me it’s interesting to compare the film to films that are actually not about soldiers, and some models for me were films that ask you to think about whether the protagonist is crazy or whether in fact they are doing fine and the world around them is a little crazy. And I think in a way those are models for me and I don’t know whether they are or are not like these other war films.

I think so many films about returning soldiers take for granted that soldiers are somehow inherently damaged people. And I think because I am interested in these other kinds of films, I wanted to pose the question, “what if Kelli’s not especially damaged at all, but that she’s lost her capacity to live comfortably in a world that is more damaged than it should be?” Not enough meaningful work, and maybe too much drugs, and other things around her that actually are a little bit crazy, and maybe she’s doing fine but she just kind of can’t take that on anymore.

You have the character of Bud discuss the difference between the apathy of returning back, people not really caring and not asking a lot of questions versus kind of more invasive, needling someone to talk about their experiences. Ut never really seemed to land on one side or the other. Do you personally have an opinion on which one of those is preferable, or is it a case by case thing?

You know what, you’re the second person that asked me something like that today and what I said to him I also have to say to you, which is; there might be a really good answer to that but I might be, like, not qualified to answer it. I definitely heard a lot of people tell me that they got a lot of stupid questions from civilians that they viewed as not understanding, so that some forms of taking an interest might be unwelcome.

Also, I had people tell me that a lot of times people think they’re ready to take an interest and really ask them serious questions and then when they hear the answer in fact they’re completely not prepared to hear the answer, which also is very disappointing. I think that kind of the challenge of crossing hat gap of empathy between people who have been in an intense war experience and people who have not is a big gap and I don’t know what, besides time and whatever, seems to be the gentlest form of companionship.

The characters that you have are all in varying degrees incapable of helping her, and some of them, like her husband Mike, actually hurt her. And yet there’s never a judgmental tone taken with them. I was wondering if while writing you had a moment where you decided that you didn’t want to throw condemnation down on people too harshly.

Well, I’ve definitely met people in my life that deserve it. It’s not like I don’t think anyone deserves judgement or whatever, but in the situation of the film I think that sometimes, and I understand this because the film is very close to Kelli’s point of view, and people sometime are judgemental towards Mike, and I think the film wouldn’t work if people didn’t have that reaction. But I personally don’t judge him because I think that he is also in a very hard situation and to me it’s not so much his personal failing as it is that some gaps are just very dificult if not impossible to cross. So I’m not going to judge him for that, even though if other people do I can see how they would. It’s not his personal failing so much as it is that he’s just in a very difficult situation.

How do you think the film would have been different had the protagonist been male? Did you feel that you could achieve something different by having a female protagonist?

There’s specific things that, because the character is a specific person and because she’s a woman, there are things in the story that are specific to her being a woman. And a lot of the women that I talk to when I was researching the story definitely did think that there were specific things about their experience before, during, and after their deployment that would have been different than if they were men.

Many of the things that they talked about were also in common with things that I learned from men, when I talked to men who had been deployed. So, I would say yes and no, there are some things that definitely would be different in the same way as if I had made her, like, from the South, or like from Great Britain. The same way as if she was different in other ways. And definitely I think that the in the film and in reality there are things that people expect of a female soldier, in terms of how she is supposed to fit into her world, that are probably different than what they expect of men. That just seems really true to me. And at the same time some of the core things of the film, like how does this gap open up between people, there is a lot of that in common with the stories I heard from men.

The thing that I think would be the most different about it as a story and a film would have to do not so much with the facts and the character or the specificity of his or her experience but I just started showing it in the U.S. and one of the things that I’m hearing I didn’t quite expect, but I think that people are just not as fmailiar with seeing a story about a female soldier. So somethings that are common to men and women they feel in a new way, because they are not expecting it. Like men and women have been leaving their children to fight in wars for a long time, but a lot of people are like, “oh my God, soldiers have to leave their children?” And I think that in this sort of separate civilian culture that I’m talking about, that seems very unfamiliar to people. So I think there is some way that because it’s unfamiliar it allows people to rethink things that they might have thought they knew.

Have you been able to hear any reactions to the film from soldiers?

Yes, just recently, actually. We premiered the film in Europe, in Cannes, and there actually was one military family there, but most of the people were film industry people. So really the last couple of weeks were the first time I heard responses from military people. And honestly I didn’t know what to expect just because a lot of the soldiers I know don’t especially like to see fiction films at all. Especially not ones about war stuff.

I felt very humble and uncertain what to expect for many reasons. So at least the people that have seen it so far have been very generous and have said that they felt very recognized by the film and so I was relieved. Obviously I hoped that people would feel honored, but you don’t know. So it was really gratifying to me to have people have that response.

Was there any pushback trying to get the film made?

Yes and no. We started trying to finance the film in the fall of 2008, which you may remember for its giant economic crisis. So, I don’t know if I got more pushback than any other independent film, because it probably took about a year and a half to find the right partner. And if you ask some people that’s a long time, and if you ask other people that’s not very long at all. People did say that about making a war film. People also said that about making a woman-led drama. Both of those are things that people think no one cares about. But I’m not sure. A lot of those other war films that have come out in the last ten years actually did make money, they just didn’t make as much money as they cost.

Right.

Which is not that they have no audience, it’s just that the audience perhaps weren’t scaled right for the marketplace. It’s not like the world is completely indifferent. When we did find our financing partner, which is the company of Abigail Disney, then she proved to be an awesome partner because she has a Ph.D. in coming home war narratives. She has a film company that does films our size. She has a feminist foundation, and she just made this amazing PBS series that’s sort of about the flipside of the equation, which is called Women, War, and Peace, and it’s about women in the hot war zones of the world like Columbia and Afghanistan and Bosnia and Liberia.

So once I found the appropriate partner, she couldn’t have been more appropriate, and she felt that it was a good idea to make a war film, and a good idea to make a film about a woman. All those things to her were smart decisions and the scale of it seemed to make sense to her financially. So once we found that person it was not a problem at all. I can’t say whether the path to her was harder or easier than it would have been with some other idea.

You talked about it being a woman-led drama. Was there any kind of reaction to it also being directed by a woman?I

I have not really heard a lot of suffering about that. It may be that I have suffered but it’s been behind my back.

I ask because when Kathryn Bigelow won [the Oscar] for The Hurt Locker there was a lot of that same kind of, “a woman just won an Oscar, and it was for a war film!” So there was that moment where it was like the world was upside-down for some reason, even though it was really just kind of turning right-side-up finally.

(Laughing) I think that was helpful to us actually, because at that moment it kind of became clear that people could at least take interest in a war movie.

Do you have any other projects in the works right now?

I do. I have a new feature that I’ve just been working on the rewrite with the writer, but it’s based on an Alice Munro story, and the write is also a lovely literary writer, this guy Mark Poirier. He’s the writer but I’ve been working with to make this draft. And we like the draft now and we’re going out to cast with it.

Do you have anyone in mind?

Yes. (Laughs)

Are you at liberty to say who your dream casting would be?

No, I really can’t because you just don’t know what will happen. It’s a wonderful performance film, also a big lead for someone. In an Alice Munro story it’s really about these beautiful small things that happen between people. Anyway, I don’t know exactly who that person is going to be, but whoever that person is is going to be awesome.

Return is now on VOD and hits limited theaters on February 28th.