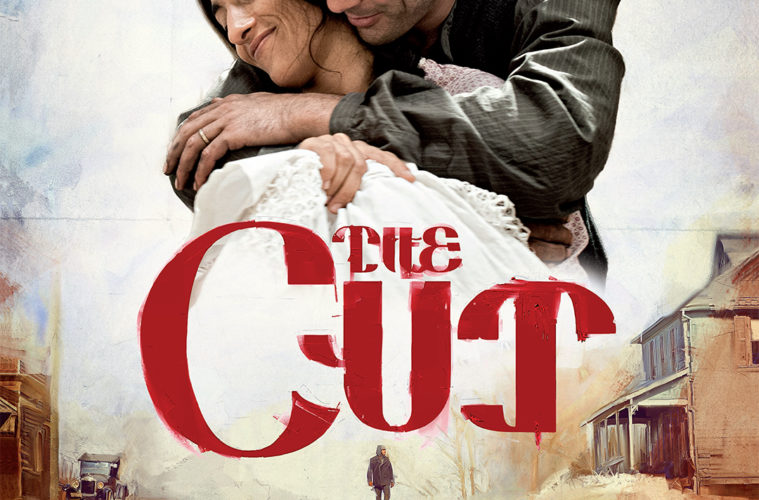

After mysteriously withdrawing from Cannes a few months back, Fatih Akin‘s The Cut lands at the Venice Film Festival as one of the highest-profile titles in their Competition. It is a sprawling, ambitiously global co-production dealing with the Armenian genocide of in Ottoman Turkey circa 1915, to this day both a controversial topic amongst the Turkish and an under-represented film setting.

A Prophet‘s Tahar Ramin stars as Nazaret, an Armenian blacksmith in Mardin forced to leave his wife and two daughters in order to join the Ottoman war effort. Such a formula sadly translated to slavery and murder for 1.5 million Armenians and other minorities, but we don’t see much of that in Akin’s film. This is mainly the story of a personal journey, as Nazaret makes it out of the conflict to learn that his two daughters are still alive, somewhere.

Though punctuated by unspeakable suffering, Nazaret’s odyssey from Turkey to North Dakota is played as the archetypical hero quest – less an unlikely product of tragic circumstances and more a pre-determined parable of endurance. As the last entry in a Love, Death, Devil trilogy (following 2004’s Head-On and 2007’s The Edge of Heaven), its historical devils are never really front and center, and The Cut could, in fact, be described as the most hopeful genocide drama ever.

Far from being an issue – Akin’s cinema has always possessed a fresh, invigoratingly positive energy, and it’s good to find it very much alive here, fighting against the nasty pull of history – it nonetheless requires some reframing on the part of the audience. It’s a more abstract and philosophical endeavor than anticipated, only to a certain extent concerned with illustrating the brutality of the Armenian Massacres. Nazaret’s journey doesn’t just survive a conflict; in some ways, it blazes through the entire 20th century in the span of a few years. On this path there’s iron to bend, soap to write names on, a railroad to build, and a magical sheet you’re not supposed to look at (“the moving image is the work of the devil!”). The character himself was meant to be an icon rather than a complex human being, and a mute (the “mark of the hero,” as well as the price paid for having his life spared) Ramin is left working with his deep, black eyes to make sense of this new world.

There’s a shadow of the muscular, old-school epic walking alongside The Cut, but I don’t think Akin can really do a straightforward epic, ever. His sensibility is more heterogenous than that, which is why the gigantic scale and the literalization of his key “journey back home” theme don’t really mesh. Enlisting the services of Mardik Martin (the writer of some of Scorsese’s masterpieces – with Scorsese himself mentioned in the credits as “My Master”) and Alexander Hacke (who writes and performs a bold, propulsive, semi-electronic score, flirting with western atmospheres and gaining momentum as Nazaret’s search nears its end) only highlights Akin’s natural inclination to smash together different moods and narrative beats.

You’d be forgiven for thinking he might have expunged this from his system in 2009’s Soul Kitchen, an unapologetic crowd-pleaser meant to somehow cap off a phase of his life and career. If that was an end, The Cut could be a beginning — it’s about fatherhood, after all — and it certainly bodes well for Akin the filmmaker, who pulls off impressive visuals and sweeping, complex shots (the horrific camp visit of Ras Al-Ayn is a striking example) over multiple continents. Let’s hope that the next stop will bring us closer.

The Cut premiered at Venice and opens on September 18th, 2015.