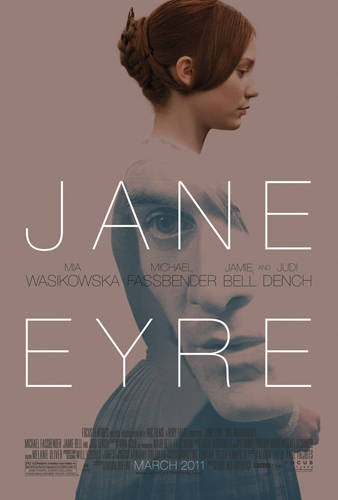

Surrounded by flickering candles and scorching flames, the characters in Cary Fukanaga‘s Jane Eyre tell little and show much from start to finish, officially announcing the young filmmaker as a force to be reckoned with, as well as reconfirming the screen presence of both Mia Wasikowska and Michael Fassbender, who star as the titular Jane and the Byronic Edward Rochester, respectively.

The film opens on a tilted frame, Jane running into a never-ending plain, frightened and crying. She falls into the fetal position. Suddenly, with a splice, she’s half the age she just was and spunkier than any of the other young girls around her. Fukanaga never crowds his frame with “so many years later” or anything of the sort. He trusts his audience enough to follow the story being told. Amelia Clarkson captivates as the young heroine, who’s taught viciously by her ruthless aunt (the smartly cast-against-type Sally Hawkins) and the sorted instructors of the boarding school she’s banished to how to be dependent to God and never independent.

A smart girl, she learns how to fake it, and fake it well. By the time we return to Wasikowska’s Jane, we see her independence in her paintings and drawings. We see her independence in the young actress’ smirks and curious gazes. There’s very little dialogue throughout the film; the majority of the sound comes courtesy of Dario Marianelli‘s subdued score, which peaks only at those moments it needs to.

Fukanaga directs in this way, allowing his cinematographer, Adriano Goldman, to mold his stars’ faces, only introducing drama when there is no possible way it can be restrained any longer. Consider the first meeting of Jane and Rochester. The governess frightens the man’s horse, tossing him to the ground. He growls and mumbles, gets back on his horse and goes. Minutes later, Judi Dench‘s Mrs. Fairfax informs Jane that Rochester has arrived. When Jane finally sits down across from the Master of Thornfield Hall, it takes two minutes for him to even look up at her. Then, and only then, does their first real dialogue begin: a tit-for-tat conversation that cements their kindred spirits.

Fassbender speaks with a deep, booming voice and stands above the rest of the cast like a titan. His Rochester is a hopeless romantic waiting for a reason to suffer for more than his past. A Mr. Darcy of sorts upon his introduction, we watch his face melt at the mention of one Richard Mason. This is not a nobleman built on his wealth or social position, but rather broken by it. So it is that the poor governess is the only who can save him. And though this sort of timeless romance has been done and done and done again (this being the 29th Jane Eyre adaptation), Fukunaga finds something original in the silence and the natural light his film boasts. Fans of Barry Lyndon will be pleased, as will those who enjoyed Joe Wright‘s modest retelling of Jane Austen’s Pride And Prejudice.

There’s both an accessibility and an artistic touch to this film that highlights a myriad of talents from all involved. This is the kind of filmmaking that should celebrated by audiences and critics alike: when a story is told and told again, and then finally told like you’d never heard it before.