3 Faces is the fourth film Jafar Panahi has made in defiance of a 20-year filmmaking ban the Iranian government issued against him in 2010. The first three were all small-scale affairs, shot solo or with tiny crews, in which the camera never left the confines of a given space – Panahi’s apartment building in This Is Not a Film (2011), a holiday house in Closed Curtain (2013), and a taxi in Taxi (2015). His newest, which sees him working with a larger team, is almost entirely set in a remote village in the mountains, likely in Iranian Azerbaijan. This shift is in keeping with the thematic trajectory drawn by this series of clandestine films. While the first one focused on Panahi’s own predicament, each new installment has expanded the scope of his critique, encompassing further facets of the oppression engendered by the authoritarian values that hold sway over large parts of Iranian society.

The prologue shows a video message that a teenage girl shot of herself with her phone. She accuses the intended recipient, a famous film and TV actress, of ignoring her many pleas for help. The girl had already sent several messages asking the actress to convince her family to let her attend a conservatory, so that she too can fulfill her dream of becoming an actress. As none of these were answered and the family still refuses to let her go, the girl says she is left with no choice. She then approaches a noose that is hanging from an overhead branch and puts her head through the loop before the phone abruptly drops to the ground, ending the video.

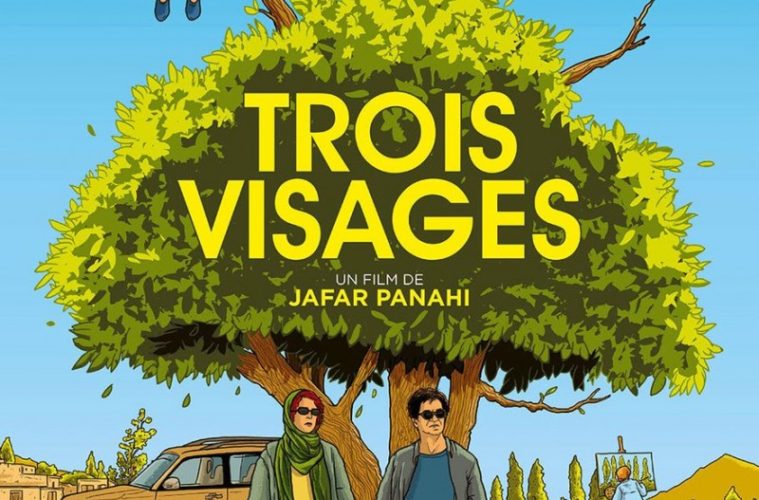

In the next scene, the actress Behnaz Jafari and Jafar Panahi, both playing themselves, are in a car together. Jafari, who is watching the video in tears, doesn’t want to believe that it’s real, insisting it’s a put-on. Panahi doesn’t think so, but he agrees to accompany Behnaz to the girl’s village in order to find out. The mystery is resolved not long after their arrival, at which point the film’s narrative shifts gears to a more contemplative mode, following the pair as they spend a day and night in the village meeting with various locals. Much as Taxi was reminiscent of Ten by Panahi’s erstwhile mentor Abbas Kiarostami, 3 Faces recalls the latter’s The Wind Will Carry Us in the way it places characters from Tehran in a rural setting, using their exchanges with the locals to invite reflections on the differing values and traditions of their respective milieus. 3 Faces, however, doesn’t come off well in the comparison, as Panahi can’t match the thematic and aesthetic complexity of Kiarostami’s masterpiece.

That’s not to say the film is without its pleasures. There are several instances of tender humor, as in one particularly funny scene where an old man tells Behnaz about his superstitions surrounding foreskins and ends up giving her his son’s to pass on to Panahi, asking that he bury it in Tehran for good fortune. The director’s characteristic humanism and rejection of easy judgments suffuses the film with sincere empathy – refreshingly, he acknowledges his own role in the entrenched patriarchal culture he’s critiquing, both as a man and film director. As such, when 3 Faces closes on a bittersweet note, the hopeful gesture of its closing image feels neither cheap nor unearned.

3 Faces premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and opens March 8. Find more of our festival coverage here.