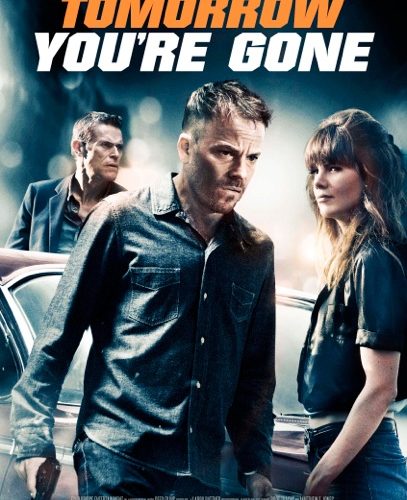

Directing his first film since 2005’s Down in the Valley, David Jacobson finds himself in very similar tonal territory with Tomorrow You’re Gone. Written by Matthew F. Jones from his own novel Boot Tracks, the story picks up with introspective, tormented criminal Charlie Rankin (Stephen Dorff) upon his release from a four-year stint in prison. Deciphering a contracted hit in a coded letter sent by The Buddha (Willem Dafoe)—his wealthy friend and mentor long since freed—Charlie finds himself holing up inside a seedy bar/motel to gain his composure before doing the deed. But as memories of past trauma begin to blur the line between dream and reality, an easy job for easy cash proves just the opposite.

Meeting easygoing porn actress Florence Jane (Michelle Monaghan) only escalates his problems as the cold heart he’s cultivated through a long, arduous lifetime begins to thaw. Feelings of love, longing, and passion lead to guilt and regret as he questions his actions and the path he’s chosen to honor the man who took him under his wing and gave salvation. Free from the system, the outside world only holds the pain and suffering that pushed him towards crime in the first place. Buddha’s gift of cash and a gun inside a bowling bag beckons him to give into temptation, but the want of a clear head to do so doesn’t stand a chance against Florence’s soft words, striptease wardrobe changes, and brazen desire to be loved.

With a deliberate pace pulsing to the music’s slow beats, one wouldn’t be wrong thinking the film inhabits the 70’s after Charlie and Florence buy a classic car in dated costume-like clothes. Between this aesthetic, his Southern drawl, and the metered delivery of lines, Tomorrow You’re Gone exists as though in a parallel dimension. Time gets lost as transitions occur through Charlie’s visions and emotional outbursts, keeping us on our toes as the two-day duration changes from light to dark to light to dark. The prospect of joy and relief clouds his judgment as Florence proves disinterested in his actions once she senses the purity of his soul. Desiring a chance to save him in the opposite way of Buddha, Charlie becomes saddled by angel and demon whispering into his ears.

A less effective relative of Badlands and The Killer Inside Me before it, Jacobson handles his newest lost soul seeking redemption—after Edward Norton‘s Harlan in Down in the Valley—with much more ambiguity. Dorff fantastically portrays paranoid fear, making his Charlie cautious to a fault against random strangers attempting to steal his bag and unwaveringly chaste to not be distracted from his purpose. Willing to let rage take control in daydreams of vengeful murder through thin walls of his temporary home, it isn’t until a chance meeting on the subway with Florence the day he’s to commit real homicide that we truly wonder if anything is real. Dafoe’s enigmatic Buddha is as believable as he is a possible hallucination while Monaghan’s Florence provides a beacon of spiritual hope.

Delicately handled so all major violence occurs off-screen—allowing us to question the predator versus the prey as well as the actions occurring, we’re never fully aware of how far Charlie will go. Given one mission to earn his place at Buddha’s side, the guilt ravaging his soul becomes an albatross of emotion he simply cannot handle. If he opens himself up to the advances of Florence, everything he feels inside his nightmares will surface and consume him. So while he aspires to live the rich life if only for a day, the prospect of a lobster dinner with a female he may actually like causes the weight on his chest to increase to the point of suffocation unless he can find a way to make things right.

It all comes to a boil when present indiscretions are laid bare without the warping of his mind to confuse truth from fiction. His way of life and the choice of whether or not to continue it are tested as Florence and Buddha stand waiting for his answer. Ambiguity dissolves and a bittersweet resolution arrives the only way it truly should. The journey here leaves enough mystery to captivate alongside its complex characters seemingly existing as extreme versions of their true selves inside our conflicted lead’s mind. More rewarding than most mainstream fare yet perhaps not as intelligent as the indie crowd would like, Tomorrow You’re Gone provides an intriguing 90-minute mood piece with nuanced performances making it a worthwhile view.

Tomorrow You’re Gone hits limited theaters on Friday, April 5th.