Cinematographers collaborating with Martin Scorsese wouldn’t expect a brisk assignment, but even a veteran of Rodrigo Prieto’s sort had plenty to handle with their latest, The Irishman. A 209-minute epic with numerous locations, multiple shooting formats, and, you’ve probably heard, distinct visual effects–it’s tiring just to think about. Prieto is nevertheless casual in his assessment, and our interview at this year’s EnergaCAMERIMAGE covers its scope from both the most specific angle and on a gut level.

For that–and an obligatory question about the short he made with Scorsese, Leonardo DiCaprio, Robert De Niro, and Brad Pitt that was never officially released–read on.

The Film Stage: Let’s start at the beginning: The Irishman opens with a tracking shot set to vintage music—not exactly unknown territory for Scorsese. But it surprised and excited me because there’s a jankiness at play: we can detect the footsteps of whoever’s holding the camera, giving this sequence a homemade quality. When and how did that creative decision emerge?

Rodrigo Prieto: It’s interesting you’d say that, because some cinematographers have complained to me about that–well, a cinematographer. I think the intention of that shot, certainly that rhythm, was important to Scorsese. As we were shooting it, he already had the music in his mind, and I believe he was actually listening to it as we shot it. It was tricky for the operator–it was Steadicam–in the sense that when it’s a very linear shot, like the whole beginning down the hallway, it’s very hard to maintain the horizon and all these things. And getting into the second area was technically complicated to get to; we had to build a little ramp. The sort of weaving aspect–or the word you used, “jankiness”–was not totally purposeful, and Scorsese usually complains about Steadicam not being really steady, like a dolly shot, so he’s not a fan, even though he’s used Steadicam classically in some unforgettable shots.

On this one, when we were rehearsing it and it had that quality, he liked it, even though it wasn’t the intention. Even in post-production, as I was color-timing the movie, I remember looking at it and saying, “Maybe we could stabilize it.” Pablo Helman, from visual effects, was there and said, “Yes, I suggested from the very beginning, but Scorsese said, ‘No, I like it.’” He refused to stabilize the shot, and I think it’s because of what you’re describing, precisely: it does feel like someone witnessing this, and the whole narration of the movie is Frank Sheeran talking to someone. Originally, in one version of the script, he was going to be talking to a priest that went out, and as we were shooting it wasn’t clear–because we shot that towards the end of the film–to me who he was talking to. It was only two or three days before we filmed it that Scorsese explained he’d talk to the camera. I think it’s inspired, maybe, a little bit by how the book is written: Frank Sheeran confesses the whole thing to Charles Brandt, the writer of the book, so I think that’s the notion: like he’s talking to the author of the book.

You’ve described Scorsese as non-technical, in the sense that he isn’t specifying, e.g., what lens to use–that it’s more about feeling. After a number of collaborations, are you able to easily discern what onscreen is you and him?

Oh, I can definitely know exactly what was what. Absolutely. To me, in the end, it doesn’t matter so much because I strive to participate in great movies, and whatever contribution I can make–even if people don’t know that’s what the cinematographer proposed–it doesn’t matter. One pet peeve is when people tell me, “Oh, I didn’t like the movie too much, but I loved your cinematography.” What was the point? I was trying to make this cinematography for that movie, not a thing of my own that’s separate. So that collaboration with the director and finding the lens or movement or lighting or color or texture with all the other departments as well, it doesn’t matter who, in the end, had the idea. What matters is the result.

Every director’s very different. For example, Ang Lee is very specific about focal length and exact position of the camera–everything. So that’s his comfort zone. I remember at the beginning, when we did Brokeback Mountain, it was odd; I wasn’t used to that. I was used to, let’s say, more freedom. That’s fine because he has very good taste, so he wasn’t going to propose shots that were bad. With Scorsese, he really does design the movie. He has a very clear sense of the shots, how they will cut together. He really thinks a lot about the editing, and the movement of the camera is really determined by the energy he’s trying to give to that moment and the arc of the drama–again, thinking about how it’s going to be edited. So he really is specific about that, but, within it, I propose the exact shot. I show him with the viewfinder; sometimes I record it on video and show him the first position, the second, “Is this what you’re thinking?” But he won’t say, “Okay, if that’s a 25, give me a 27.” He won’t be like that. He’ll just say, “Give me more energy, be slower, faster, more extreme,” whatever it may be. But he uses that language rather than technical specifics.

One specific talked about much is the “de-aging.” I don’t know if there was a specific term used to describe it.

I would say “de-aging,” probably.

Sequences requiring that are shot digitally.

On the RED Helium.

And others are 35mm.

Yes.

I was surprised to learn this–after seeing the film, because it felt pretty seamless during. Kind of as The Wolf of Wall Street’s blending of digital and celluloid did, actually. Tell me a bit about the processes of ensuring this.

That certainly was a very important factor in the whole design of the movie. Very early on I felt it had to be shot on film negative. But also, extremely early on–like, the first conversation–was with [visual effects supervisor] Pablo Helman, and he explained how he needed to shoot digitally the visual effects, because with the witness cameras, it’s three cameras to be perfectly synchronized. Also, we had to have them move exactly the same. Three film cameras would’ve been too big for this, so there was kind of a push to do the whole thing digital, but I really insisted the look of the movie had to be film because of the memory aspect of it. Also, Scorsese told me early on that he envisioned a feel of home movies, but he specifically said, “I don’t want it to be shaky handheld or grainy Super 16, that sort of thing.”

So I felt it had to be on film, first of all. Then my discussion with Pablo was, “If we shoot just the visual effects scenes digital and the rest on film, you have to guarantee to me that ILM will help me make them match.” He guaranteed it, and ILM has, obviously, much experience in “graining” CGI for movies, so he had all that. But color was of the essence to me. I came up with a design, because of what Scorsese said of the memory and home-movie aspect, that instead of emulating home movies, maybe we can emulate still photography–amateur still photography. So I did deep research into Kodachrome and Ektachrome. Kodachrome, to me, feels more like the ‘50s–even though it’s been popular for many years beyond–and its colorization is very ‘50s. Ektachrome felt a bit more like a more modern still-photography emulsion. So I thought, “Let’s give the ‘60s an Ektachrome feel.” We developed look-up tables to very closely match the way these emulsions track the color. The trick was to map those colors into the digital camera, the look-up tables, and the dailies of the film camera. It’s color-mapping, and a color scientist, Matthew Tomlinson at Harbor Picture Company. With them I also did the digital intermediate.

So when I tested different digital cameras, the one that reproduced the look-up tables the best and matched color the best was the RED Helium. That’s why I went with that one specifically. Maybe if it had been a different look-up table it would’ve been another camera, but these particular tables match that. Then I changed in the ‘70s and beyond: instead of the memory thing, I decided to go with a look that was a little desaturated color. For that we used an emulation of a process called ENR that was developed in Rome, at Technicolor. It’s a process done with the printing of certain movies; Vittorio Storaro did it on one movie, and I did it on another in Mexico. What you do is skip the bleach process and printing of the film. The result is less color saturation and more contrast. So I did two versions of that. In the early ‘70s it was a light thing–even when they’re in the car on the road trip, it’s an ENR lite, so a slight desaturation but pretty natural. But right after Hoffa was killed, we went to ENR extreme. You remember the scene where the family is watching TV?

Yes.

That’s kind of drained of color, and so is everything else after–even the nursing home. All of that is very colorless. So, for me, it made sense that the movie, the journey of this guy, is learning about these guys, the mafia, the union, all that. Then, once Hoffa’s dead, all that color goes away.

With all these different formats, effects houses, and processes, how much does Netflix affect post-production? Are you using their resources at all?

Actually, Netflix was very flexible with what we wanted and needed. There was absolutely no intervention in terms of, creatively, notes or anything like that. In the beginning there was this thing about 4K–that’s a requirement–and that’s one reason I tested the Helium, because I hadn’t used that camera and was a little skeptical, frankly. But I said, “Okay, that camera is 4K; let’s see what it looks like.” And I was surprised: it worked very well with the look-up table. Film, of course, is beyond 4K, so that wasn’t an issue. Although, in the beginning, they were, “We don’t do film negative,” but then they were totally okay with it. I definitely think it was worth it.

In post-production, the only thing was: when we were doing the version for television, we did two versions: one is high-dynamic range, and, from that, the regular arrives. I must say it’s pretty exciting. To see the film in high-dynamic range is amazing. You see the richness of the highlights and lowlights; it’s very beautiful. For screen, we did a version–and I don’t know if they’re going to project with this–that’s Dolby Vision, similar to HDR but for the cinema. It’s amazing. I think those are my favorite versions. You really get the rich, deep blacks and the highlights have much more detail. That was the only thing.

Apart from that, we worked at Harbor Picture Company, which I chose, and Yvan Lucas, who I’ve done many movies with, was my color-timer. He approaches color-timing in a sort of simple way, because he started as a photochemical color-timer in France, at Eclair, and that’s how I met him. I try to keep to that philosophy. Once I set up a look-up table, which is equivalent to a print, then, within that, I just do brighter, darker, red, green, blue–the basics of primary color-correction. Then I’ll do some windows and things like that, but I very much try to approach it as if it were photochemical.

Most seeing The Irishman won’t be at the mercy of a theater and projection system, but many home set-ups are especially inadequate. I wonder if you’re concerned about people seeing it on TVs with motion-smoothing, bad calibration, and the like, and not having any control over it.

No, it is a concern, and unfortunately there’s not much you can do about it. Except that there is a push now, when the ASC is participating in that, to be able to have the option on your TV to have an actual cinematic control–a button, basically, where you can see it the way the filmmakers intended. So that takes away all these smoothings. Hopefully that’ll come into play, but it’s always been a tricky thing–even with projection, especially when it was film. The prints are all different, so one reel may be a little green, etc. You maybe will do two or three perfect prints, but beyond that, it’s really hard to control, and it’s kind of frustrating.

But you try to have your control, your main thing, be as accurate as possible. Hopefully all the other monitors and screens will be relatively… but you can’t chase that. I remember, when I was in Mexico, the color-timers would say, “Let’s make the movie the way you like it, and the prints will be three points brighter because all the projectors are dim.” It’s like, “What?! But what if not? Then you have a good projector and it’s super-bright!” So my philosophy is: do your master at your liking and hope for the best.

EnergaCAMERIMAGE is especially good with presentation.

Yes. I just did a little test before the screening and it was great. My wife was here, so I said, “You know what? See it again.” Because we saw it at the premiere and, actually, the premiere at the Chinese Theater was a little dim. So I saw it here and I said, “Monica, see it here.”

What happened to The Audition, the short you made with Scorsese? I thought it was great, but could only ever see it on a horrible YouTube rip.

It’s a mystery to me–partly a mystery–but I do know we made it for this casino. The intention was always kind of internal use for them. It wasn’t, like, a commercial for the audience, but it’s bizarre. There was even a moment where it was going to show in the Venice Film Festival, then they canceled that, so it was kind of mysterious. But it was so much fun, just seeing all these people. And I’m in it. I enjoy acting and I had this little cameo where I go around with a viewfinder and try not to laugh. It was incredible. I mean, I’ve just had so many incredible experiences with Scorsese. I’ve been really lucky with Oliver Stone, Alejandro González Iñárritu, and now Julie Taymor; I just finished a movie with her. So it’s been great to collaborate with these people.

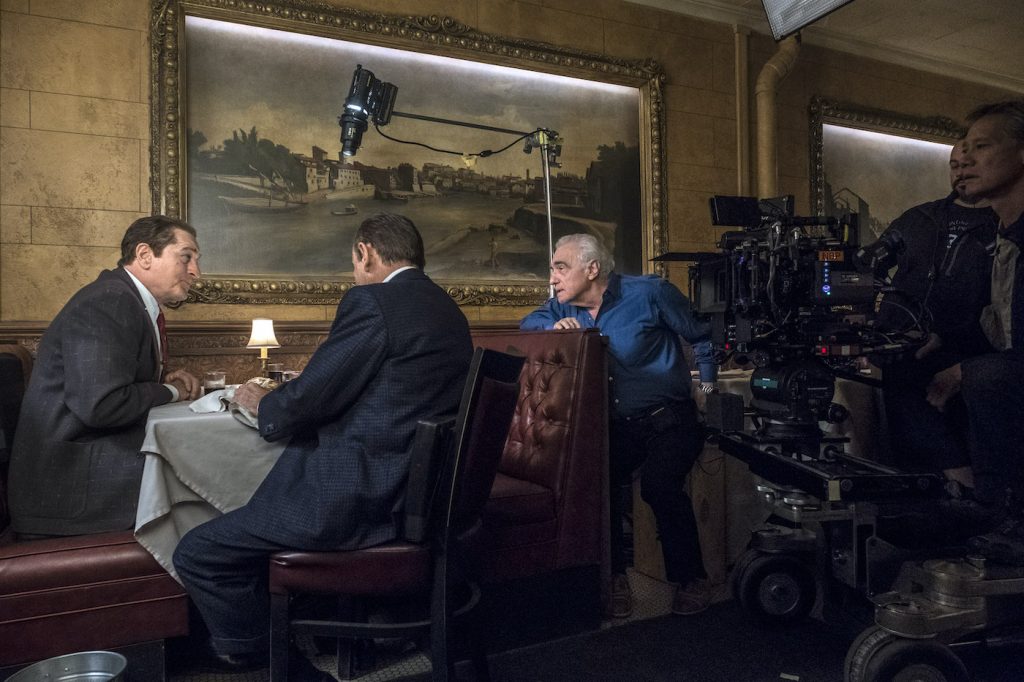

The Irishman is now in limited release and hits Netflix on November 27. See Prieto and crew at work in the b-roll footage above.