There is a certain indescribable manner in which Michael Haneke is able to lure you into his films that leaves you in a state of both shock and awe. It’s everything from the subtle use of camera movements to the minimal use of diegetic music, not to mention the carefully crafted and poignant jump-cuts in editing. These are the staples of an auteur in complete control and if this auteur’s body of work is any indication, you can never know what the director will do next. Such is the case with Amour, a heart-wrenching and unflinching portrait of an elderly couple faced with the trials and tribulations of our own mortality when confronted with the inevitable demise we all face. In showcasing the intimate pain of watching someone you love slowly suffer, Haneke takes a departure from his usually emotionally-detached narrative troupes, offering his most humane film to date.

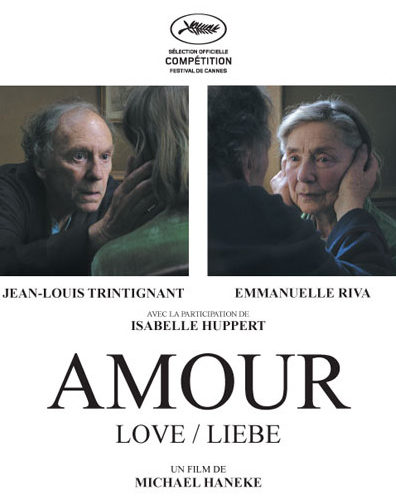

After a deliriously haunting opening shot effectively establishes a forbidding sense of doom, the camera settles on a static shot of an audience being seated for a musical performance. It is a great moment of meta cinema as the same ‘do not use your cell phone during the performance’ messages rings out just before the rapturous music of Schubert permeates through the air. It’s both haunting and beautiful, much like the rest of the film, and an apt introduction to our two principal characters. Georges and Anne are a loving couple in their eighties, played with delicate humanity by Jean-Louis Trintingant and Emmanuelle Riva. One morning while preparing breakfast, Anne suffers a stroke, paralyzingly the right side of her body. Thus begins the ultimate test for the couple’s love for one another, as Anne’s condition begins to deteriorate, forcing Georges to make difficult decisions about life and death.

Aside from the opening scene, the entire film takes place in the Parisian apartment that Anne and Georges share together. Yet the film never feels static or claustrophobic. Instead the framing of doorways, hallways and intense close-ups give each frame a tableaux quality. In addition, the gravitas of the couple’s situation anchors the somber tone in an affecting way that fills each moment with uncomfortable dread. Isabelle Huppert plays the couple’s daughter, periodically dropping by to check in on the status of her parents. As Anne’s health continues to worsen, their relationship becomes more and more strained, forcing Georges to make extremely difficult choices resulting in some cringe worthy instances. Haneke is a master manipulator of psychological emotion, but what makes this film standout among his other brain benders is the detached rawness of each painful decision he puts his characters in.

If you have ever loved someone with the entirety of your heart and then lost them to a medical condition, then you will identify with the pain on display here. It’s at times exasperating to see Georges toil over his wife as she slowly slips from the grips of life to the throws of death, reverting to a childlike demeanor. Eventually we all must face the fear of losing control of our bodies due to the effects of time, and Haneke’s focus is so precise that it’s hard to not be moved by the situation. There are also some amazing moments of cinematic genius at work, from a surreal nightmare to an encounter with a stray pigeon. Unflinching, unnerving and unforgettable, Amour is an incredible testament to the power of love we have for those closest to our hearts while forcing us to question the very essence of our own morality when confronted with the clocks of fate.