High above the Nepalese mountains, inside a doomed aircraft, exploring the studio of a legendary animator, a look at the greatest film never made, a pastor’s struggle to make the world a better place, an unprecedented whistleblower, a race for scientific discovery — these were just a few of places and stories the year’s documentary offerings brought us. With 2014 wrapping up, we’ve selected around twenty features in the field that most impressed us, so check out our list below and let us know your favorites in the comments.

20,000 Days on Earth (Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard)

In order to show Nick Cave‘s true self, directors Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard give us a filmed curio cabinet of relics and recollections, somewhat akin to the video for Johnny Cash‘s cover of “Hurt” if he had given us a tour while singing. And it’s the perfect depiction because Cave talks about the importance of memory throughout and his interest in its worth above reality. To lose it is his worst nightmare; to speak about it his greatest weapon for self-improvement and catalyst for creation. Because his narrative songs speak about real people with a “mythologized, edited memory” composed for the world to hear, it’s no surprise the film embodying his own life would prove a quasi-autobiographical journey through words rather than strictly captured images. We therefore receive a glimpse behind the façade at his truth above celebrity. – Jared M.

Alive Inside (Michael Rossato-Bennett)

A film about Alzheimer’s is rarely uplifting. Anyone that has dealt with a family member or close friend that has gone through this debilitating disease is keenly aware of how troubling it is. Yet Alive Inside finds that amidst all of the progress in care there hasn’t been much in terms of medicine. But a new method is taking hold around the country: the power of music. It awakens the person that is often trapped inside of the people suffering from Alzheimer’s. Often, a documentary is hard to differentiate from its subject to glean just how well-made it is. Here, I have no qualms that, even as straightforward and plain as the documentary may be, the message is well worth the time. – Bill G.

Actress (Robert Greene)

As if Sirk and the Maysles brothers had an anxiety-ridden child (don’t ask about that procreation process), Actress is one of the few functional “boundary-blurring” documentaries of late because Robert Greene, a keen observer of movement, had discovered a perfect subject and the best story for it. At one moment intimate and comfortable, at the next an unpleasant dive into an emotional maelstrom, its shape makes one wonder that the tired “we’re all actors” maxim would be tried anywhere but the documentary format. – Nick N.

The Battered Bastards of Baseball (Chapman Way and Maclain Way)

A well-made (though thinly told tale) about the Portland Mavericks, a minor-league baseball team that operated independent of Major League Baseball’s rules and regulations. Owned by Bonanza star Bing Russell, father of Kurt, the Mavericks found unbridled success in the mid-70s, revitalizing a once-defunct baseball town. Directors Chapman and Maclain Way don’t dig much into the specifics of the story, relying on the memories of those close to Bing (his son especially) and not much else. In short, the story exceeds the documentary, which is just enough to entertain. – Dan M.

Charlie Victor Romeo (Karlyn Michelson, Patrick Daniels, and Robert Berger)

Verbatim theatre is a genre that aims to provide a certain kind of honesty through anonymity. Performances are derived from primary source documents like interviews, or, in the case of Charlie Victor Romeo, transcripts of NTSB reports of actual aviation emergencies. Shot over the course of a few evenings in a black box theater in front of a live studio audience, the film adaptation of Charlie Victor Romeo (performed since 1999) is a harrowing psychological experience. Centered squarely on the text, the film’s sets are minimal; Flight, this is not. The utilitarian cockpit set looks like something out of 1970’s Saturday Night Live, but is used to depict six emergencies with varying outcomes and durations. Often split-second decisions are made, complicating the notion of “human error.” – John F.

Citizenfour (Laura Poitras)

The invention of the Internet and other communication technologies has undeniably made the world a more connected place. With unprecedented access to cell phones and various social networks in this post-9/11 era, it’s also easier than ever for the government to track one’s every move. As the debate rages on about surveillance and if desecrating one’s right to privacy can help national security, Edward Snowden, working as an NSA contractor, made the decision to bring more evidence to the table. Considering the notion that anyone with at least a fledgling interest in current events would be familiar with the leaks and near-immediate disclosure of his identity, Citizenfour makes for a relentlessly gripping, humanistic behind-the-scenes portrayal of the events. – Jordan R.

The Dog (François Keraudren, Allison Berg)

The Dog is a lively, epic documentary biography of John Wojtowicz, an anti-hero of sorts in New York’s gay rights movement. A later episode in his life would be immortalized in Sidney Lumet’s 1975 film Dog Day Afternoon — and while that remains a masterpiece, The Dog, shot with Wojtowicz from 2002 until his death in 2006 is a complete biography, going beyond Lumet’s film and Pierre Huyghe’s 1999 installation The Third Memory. That project featured, like The Dog, a direct address by Wojitowicz walking us through the details that Hollywood made more, well, “Hollywood” in Dog Day. – John F.

Finding Vivian Maier (John Maloof and Charlie Siskel)

Working backwards from a box, co-filmmaker and historian John Maloof comes across at a local auction house, he begins to piece together the mystery of amateur photographer Vivian Maier, an American street shooter who mostly worked in Chicago. As told in the first person, Maloof and co-director Charlie Siskel have created an intimate, yet mysterious portrait that paradoxically answers and asks questions, exploring the person behind the lens, tracing her correspondences and catching up with those who crossed paths with Ms. Maier, including the children she cared for as a nanny. One of the year’s best documentaries, it’s worth seeing as an engaging guided tour of the work, life, and times of a little-known, fascinating American artist. – John F.

The Great Invisible (Margaret Brown)

Margaret Brown’s The Great Invisible is often a frank reminder of what George W. Bush once said: “America is addicted to oil.” Exploring the event and aftermath of the 2010 Deep Water Horizon explosion, Brown intercuts between those with intimate knowledge of the rig, including workers who narrowly escaped death, archival footage that also encompasses BP’s response, a frank conversation between energy executives in Houston, and the on-the-ground effects in Bayou La Batre, a hub of seafood production. At times this narrative device seems risky and perhaps disjointed, but The Great Invisible is a large and haunting story to attack. – John F.

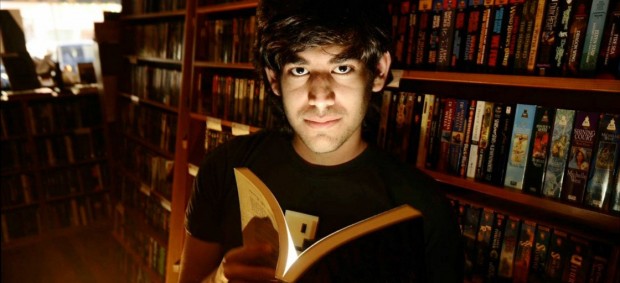

The Internet’s Own Boy (Brian Knappenberger)

If you’ve been on the internet, there’s a chance you’ve used a service that Aaron Swartz has had a hand in. A co-founder of Reddit, a developer on RSS, an organizer of Creative Commons, and countless other services, he had a phenomenal impact on what we call the internet today. Sadly, his life was cut short when he committed suicide in January of 2013, presumably due to pressure following the efforts of the government to jail him for up to 35 years and fines in the millions because of harmlessly gathering data to academic journals at MIT. Directed by Brian Knappenberger, the documentary chronicling his life and auxiliary efforts around internet freedom is formally standard, but a powerful testament to Swartz’s effort, properly defining him as a hero. – Jordan R.

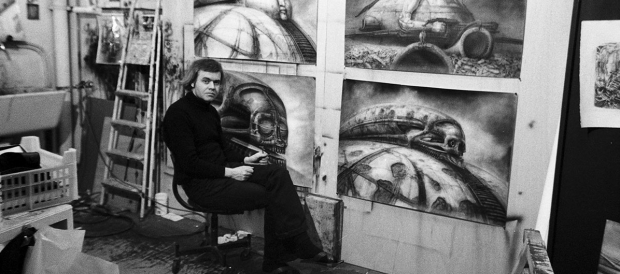

Jodorowsky’s Dune (Frank Pavich)

I went into Jodorowsky’s Dune having heard of filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky, but lacking the experience of actually watching any of his films. Yet I was drawn to his personality and passion for cinema as art. This incredible journey of Jodorowsky and his attempt to adapt the best-selling sci-fi novel Dune in the mid-70s is inspiring in a way few documentaries are. This is the tale of a film that came so close to fruition that it is painful to hear of, and yet the collaborators that Jodorowsky brought together would go on to shape the world of cinema (in films like Alien) and have various influences elsewhere. Truly, Jodorowsky’s version of Dune is a lost epic, yet director Frank Pavich manages to give us a glimpse at the picture brought to life through the filmmaker’s own voice. – Bill G.

The Kill Team (Dan Krauss)

Had he only assembled a presentation of wartime atrocities into a functioning cinematic whole, director Dan Krauss could be said to have a certified accomplishment in his war documentary, The Kill Team. Yet what comes of the effort, in full, is better: a glance at the dark side, understanding that man’s need to not merely protect, but justify the means to that end — opting not for the harsh truth of document, but using what exists of it, words and images, to explore the boundaries between fact and assertion, finally concluding that all human sense is susceptible to malfeasance in the fog of combat. For portraying without condescending and probing without draining, this is a work that stands as a unique achievement by complex design. – Nick N.

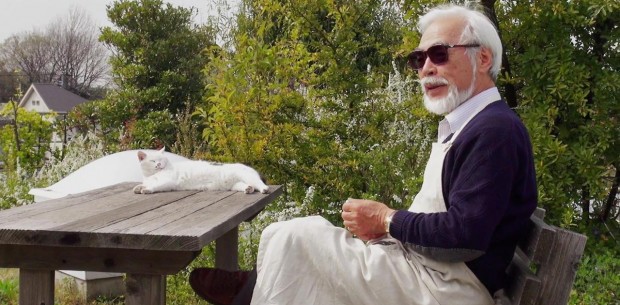

The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness (Mami Sunada)

Following the parallel productions of Hayao Miyazaki‘s The Wind Rises and his partner Isao Takahata‘s The Tale of the Princess Kayuga, two films that would punctuate the end of an era, along with the forthcoming When Marnie Was There, The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness does the world a service by chronicling and preserving, in a most charming and understated way, Miyazaki-era Ghibli and the human element beneath its creative genius. The film’s non-cynical depiction of its subjects also stands as a testament to the artistic spirit, as well as the complex and fragile, yet ultimately worthwhile journey into its pursuits. – Amanda W.

Life Itself (Steve James)

Roger Ebert is an icon of cinema. Few people can claim such a distinction, and even fewer can say they had the influence he did as a film critic. But, more than that, Life Itself is a story about how cinema can unite us, restore us, and give us something worth talking about. Ebert, even in his later years suffering from sporadic bouts with cancer, was still wholly consumed by film. But instead of holding it inside, he let it culture him and mold him as a person, and he enjoyed spreading that around. To him, cinema wasn’t just entertainment; it was his lifeblood. This story hits an apex near the end but, throughout, is entertaining, because it attempts to recant the story of his own biography completed shortly before his death. In a way, the film becomes more, and remains a shining example of what it means to live, love, and ultimately pass away. – Bill G.

Manakamana (Stephanie Spray and Pacho Velez)

The latest work from the Harvard Sensory Ethnography Lab is also one of the most powerful, transformative experiences one is bound to experience this year. Taking a different approach than Sweetgrass and Leviathan, Manakamana places us as a passenger on twelve separate trips to and from the titular sacred temple in Nepal. While some may consider it an endurance test, I found it to be a warm, vulnerable exploration of humanity, stripping down barriers that even the vast majority of documentaries can’t help but construct. – Jordan R.

Mistaken for Strangers (Tom Berninger)

For fans and newcomers alike, Mistaken for Strangers is a raw, unembellished look — not only at one of music’s rising bands, The National, but of the creative process in general. Exemplified in early footage of their humble beginnings (with concerts sometimes not featuring a single audience member), Tom Berninger harnesses in on the theme of growth and the long road it takes to achieve something substantial — whether you are a now-famous musical act or siblings that have formed a renewed bond. – Jordan R.

The Missing Picture (Rithy Panh)

What initially seems like an attempt to recapture the past through a rudimentary format slowly, steadily unfurls into something more complex: the ways in which certain memories can never leave us, the need to transmit these memories into a different space as a means of coping, and a concession of cinema’s limits in representing memory. – Nick N.

National Gallery (Frederick Wiseman)

Every Frederick Wiseman film begins with a parable that defines, as a whole, the institution on which it will focus, and one practical that defines its tension. For National Gallery, the director’s meditative look into Britain’s largest collection of classical art (located adjacent to Trafalgar square in London), our opening is a tour guide explaining a Christian triptych icon to the men and women she leads. Instead of discussing the work’s artistic merit or its visual splendor, she asks each person if they can imagine themselves in the 13th century, under what context they would see it, and, most importantly, how they would communicate with it. In the second scene, two administration types discuss the major problem with their gallery as it stands: how to address the public without lowering the standards of art. How can they communicate the old masters? – Peter L.

The Overnighters (Jesse Moss)

North America is the land of opportunity, but sometimes you have to travel to find it. The Overnighters revolves around the oil boom currently taking place in North Dakota and a small town that is flooded with people that tell stories reminiscent of the gold rush in California in 1849. Back then, towns sprung up as demand increased. However, in Williston, North Dakota, demand for housing in any form for the massive influx of workers has been heavily outstripped. Yet the tide of people continues to surge. Within this small town is a pastor that has opened up his church doors to the people seeking shelter, housing them for months at a time much to the chagrin of his own membership. This push and pull, the story of the film, becomes as powerful as any on the nature of complex issues such as religion, family, economics, and what it means to live in modern-day America. – Bill G.

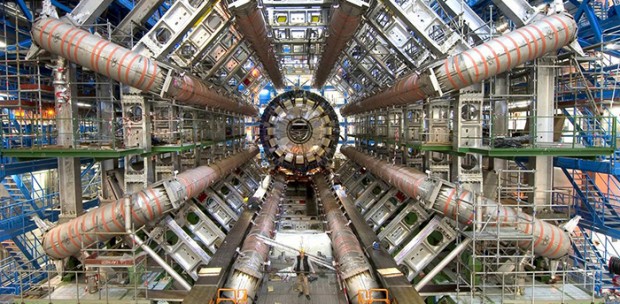

Particle Fever (Mark Levinson)

Science! You either see it as the backbone to understanding or you don’t, and everyone who doesn’t may want to avoid Mark Levinson‘s Particle Fever, because it’s first and foremost a document about the subject’s cool factor and importance. If you’re a creationist and everything you hold true about our origin comes from a book written centuries ago by multiple people who potentially had a simultaneous psychotic break to hear voices, all sense of wonder and discovery is nonexistent in the present. What point is there to search for answers when you know death brings salvation? Only in Paradise can you discover something new and real. For scientists, however, the rush of adrenaline in uncovering a truth never before seen by humanity is as crucial an experience as a Catholic meeting God. They’re finding miracles. – Jared M.

Tales of the Grim Sleeper (Nick Broomfield)

The subject of Broomfield’s film – an alleged serial murderer by the name of Lonnie Franklin, a.k.a the “Grim Sleeper” – still awaits trial on ten counts of murder that occurred in South Central Los Angeles between 1985 and Franklin’s arrest in 2010. And while no civil suit against the city currently exists – as it did with regards to The Central Park Five – one could envision the potential of such a lawsuit given some of the assertions made in the film with respect to the LAPD’s handling or mishandling of the case. Tales of the Grim Sleeper is a deeply unsettling and, at times, uncomfortable examination of a story and a community given short shrift at a time when attention was desperately needed. It’s also a film that indirectly raises a number of important and discussion-worthy social questions, the answers to which go far beyond the breadth of any review. – Brian P.

Tim’s Vermeer (Teller)

Coming from the world of magic into another form of attraction, Penn Jillette and Teller debuted their first feature film, Tim’s Vermeer, this year. With the former serving as producer and the latter taking on helming duties, the documentary tracks their quest to uncover one legendary artist’s ability to create picture-perfect paintings. While anyone with a basic understanding of Photoshop can do such an activity in today’s age, the duo are looking at Dutch master Johannes Vermeer and his 17th-century works of art. They specifically follow a man named Tim Jenison, who has produced a theory of how this artist was able to create such detailed works. It’s a surprisingly engaging piece of work that will make one think twice about the master’s art. – Jordan R.

Virunga (Orlando von Einsiedel)

Employing multiple modes of documentary storytelling, from talking heads, undercover reporting, and on-the-ground war reporting, Virunga is a potentially paradigm-shifting entry in the genre that deserves the kind of support and attention Blackfish and The Cove received. The deep geopolitical conflict is embodied by the Virunga National Park, a UNESCO-designated world heritage site. It’s a 3,000-square-mile zone encompassing villages and wild life preserves, in a story told by multiple narrators that is perhaps the most direct telling of a truly complex system of interactions. – John F.

What’s your favorite documentary this year?