“A cinematographer is a visual psychiatrist–moving an audience through a movie […] making them think the way you want them to think, painting pictures in the dark,” said the late, great Gordon Willis. As we continue our year-end coverage, one aspect we must highlight is, indeed, cinematography. From talented newcomers to seasoned professionals, we’ve rounded up the examples that have most impressed us this year. Check out our rundown below and, in the comments, let us know your favorite work.

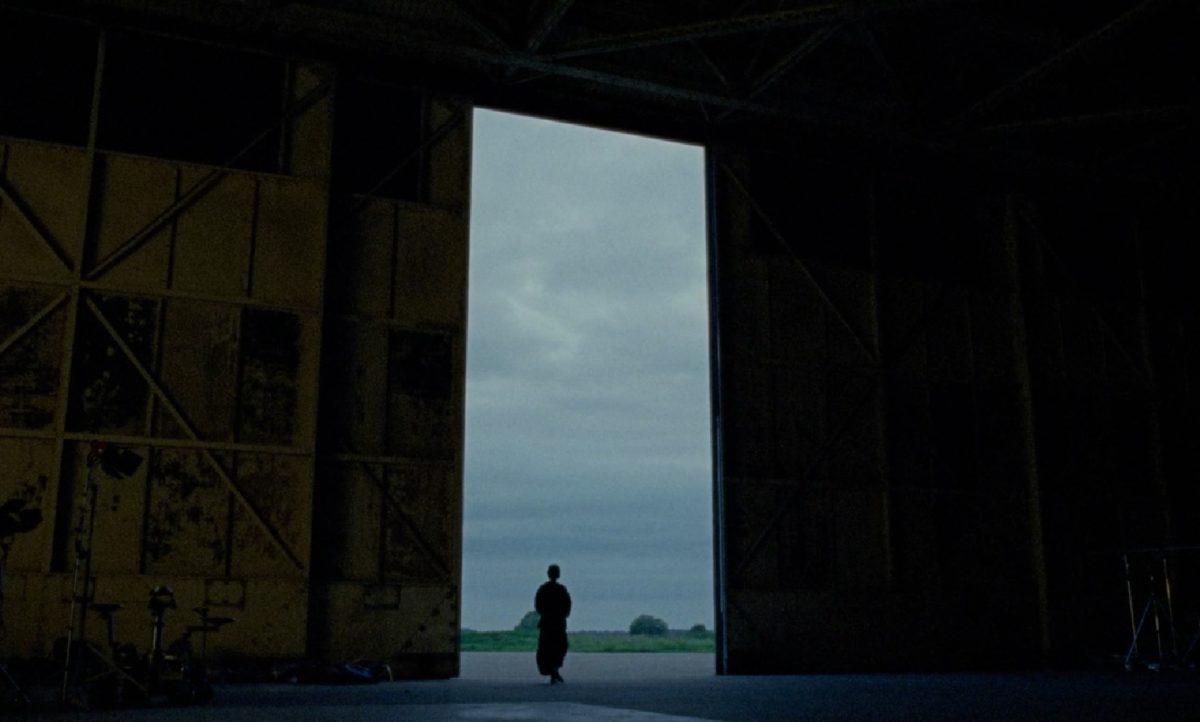

Ad Astra (Hoyte Van Hoytema)

After conducting a symphony of the senses with The Lost City of Z, director James Gray moves effortlessly from jungles and rivers to the far reaches of space. Working with cinematographer Hoyte Van Hoytema (who also lensed Interstellar), Gray photographs a man’s journey to find his father in the abyss with elegance and finesse. Like many of the great odysseys, Ad Astra is both grand and intimate, with Gray’s sumptuous image-making once again enveloping us completely. Not unlike in Z, this is a world at once textured and tactile, while also dreamlike and vast enough to render humankind as a faint crease in the ripples of time. Yet despite planetary spectacles and Mad Max-esque rover chases, the smallest details are what sing in Ad Astra–like that of a hand reaching out gently to touch particles gliding by on the moon, a simple gesture that reminds us, no matter where we are, our life is in the little things. – Mike M.

Atlantics and Portrait of a Lady on Fire (Claire Mathon)

After arriving on our radar with her striking work in the films of Alain Guiraudie (Stranger by the Lake, Staying Vertical), Claire Mathon deserves to be crowned the cinematographer of the year after shooting Mati Diop’s Atlantics and Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire. With two vastly different approaches, she places us vividly into each story with her dexterous, intimate eye. In the ghost tale within Atlantics, there’s a sense of haunting immediacy and modernity in her camerawork while her craft in Portrait is of a classical touch, jaw-dropping in its perfect painterly quality. With just these two films, we expect the next decade to be defined by Mathon’s distinct, diverse vision. – Jordan R.

A Hidden Life (Jörg Widmer)

Following a long and successful tenure alongside Emmanuel Lubezki, A Hidden Life marks Terrence Malick’s first feature without the cinematographer since The Thin Red Line. This time around, it’s Jörg Widmer behind the lens, and he steps up to the challenge. Widmer’s camera matches the tranquil, tragic narrative beautifully, Malick’s most linear in two decades. The wide-angle lenses remain in heavy use, though a bit stiller then in film’s past. As the inevitable approaches, each shot lingers on a bit longer as if capturing every ounce of beauty possible before it all ends. We’ve not often seen such an interesting face as lead August Diehl’s. Malick and Widmer know this, and make the most of their subject. – Dan M.

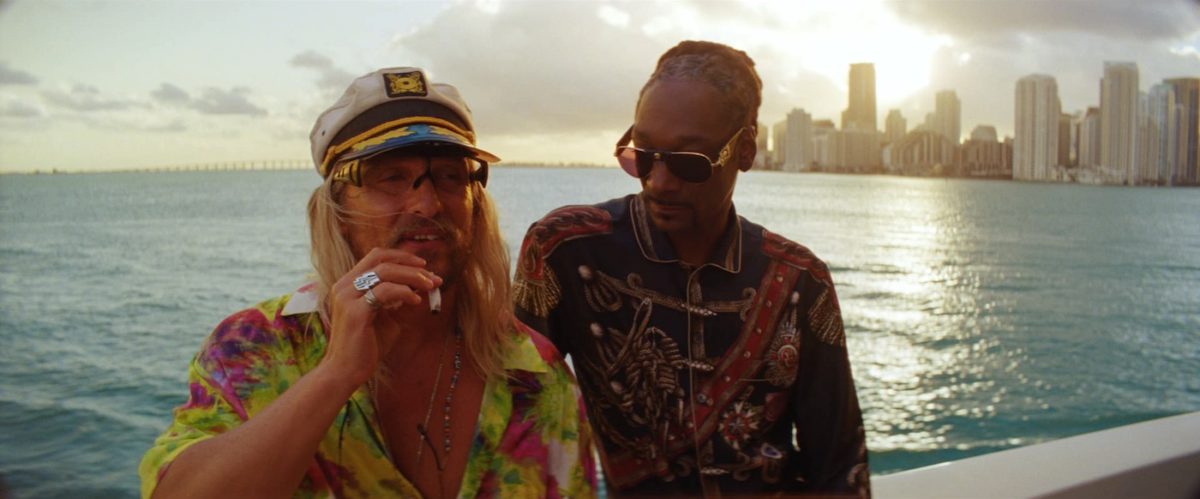

The Beach Bum and Climax (Benoît Debie)

Utilizing 35mm photography and color filtering in engaging and beautiful ways Benoît Debie–re-teaming with Harmony Korine after their incredible work together on Spring Breakers–has taken a similar stylistic approach to his photography on that film but focuses on the daylight of Miami. The Beach Bum‘s use of sunlight and extremely vivid colors portrays Miami as a much hazier and more romantic place than the darker Spring Breakers, expressing the visual representation of how Moondog sees the world around him with an exuberant spectrum. The free-flowing blissful structure of the film’s ostensible narrative wouldn’t be as effective without Debie’s photography, which lulls the viewer with a sense of serenity. Whenever the camera is moving, Debie’s control accentuates the intended sensation of euphoria as his cameras glide through the colorful city. The cinematographer is also responsible for Gaspar Noé’s latest film, which is quite divisive around these parts, but a universal point of acclaim is Debie’s cinematography. Employing long takes as his camera operators work seamlessly around its location, unlike many other long take-oriented films, Climax is operatic and built around visual bombast, with the camera gliding across ceilings and entering rooms at dazzling avant-garde angles. The commitment to color, particularly with the emphasis on bright reds, adds to the overall atmosphere of chaos, with dread seeping into the viewer as the camera continues to capture these acts of destruction. When the film finally goes off the rails, the photography becomes more chaotic itself, cinematically conveying the ways in which hatred can spread. – Logan K.

Dark Waters (Ed Lachman)

Marking the fourth collaboration between Todd Haynes and veteran DP Ed Lachman, Dark Waters expands on the paranoid imagery that has made the filmmaker’s brand of outsider cinema so effective over the years. Whereas predecessors like Carol and Far From Heaven visually balanced the romanticized depictions of American values with grimier social tensions (creating poignant dichotomies between superficial allure with genuine connection), this latest effort is mostly just ugly. Significantly, the film is also the duo’s first digital effort, as if confirming at the outset that any beauty would be ill-suited for a topic as perilous as this. The result is an appropriately anxiety-ridden self-imploding melodrama that properly conveys the irresponsible destruction of not only the environment, but also of American morality (agrarian lifestyles and political virtue alike) by corporate greed. Haynes and Lachman make sure to catch every wayward stare and do not deign to look away from the explicitly grotesque changes imposed on ourselves and our surroundings by our progresses; one cannot help but think of Jung admonishing the Promethean debt of progress and its threat to individual desire, or of Virilio’s “integral accident.” – Jason O.

Dragged Across Concrete (Benji Bakshi)

What knuckles you hardest in Dragged Across Concrete is its stillness. From Bone Tomahawk writer-director S. Craig Zahler (Brawl in Cell Block 99) has established a lexis where each moment is treated with the same gravity and matter-of-fact acceptance. This means a jewelry store conversation plays out not unlike a masked man sifting through a dead guy’s innards in an overturned van–and vice versa. There’s a quiet, confrontational nature to all of Zahler’s images, as if the film is leaning back in a chair with its arms crossed, pissed-off but patient. It creates a textured exploitation picture, where good and bad and inbetween are muddied until all that remains is shades of grey along a continuum. More practically, this visual treatment instills confidence in the writing and performances that encourages viewers to sink into each scene, and allows character dynamics and emotions to push through Concrete’s oppressive surface. – Mike M.

An Elephant Sitting Still (Fan Chao)

One of the predominant unifying elements in the sprawling epic that is Hu Bo’s An Elephant Sitting Still is Fan Chao’s beautifully ashen cinematography, which conducts itself in long Steadicam shots that follow one of its main four characters through the decaying industrial town. In a manner similar to Béla Tarr–who was Hu’s mentor–the camera is frequently trained on faces, and the colors are such that the film appears grey at nearly every point. Yet the gracefully slow movements across faces and landscapes, the constant sense of reframing, lend their own gentleness and compassionate consideration. – Ryan S.

Her Smell (Sean Price Williams)

Enhancing an excellent performance by Elizabeth Moss, Sean Prince William’s claustrophobic cinematography serves a conspirator in Alex Ross Perry’s intense behind the scenes drama. Spending more time in green rooms and hallways than on stage, Her Smell is chronicles the ups and downs of Moss’ Becky Something over the course of her career from the highs of the 1990s to a reunion for the record label 20 years later. Williams’ cinematographer offers a bleak and energetic portrait encompassing multiple forms of video from the highs and handheld camerawork that is so gritty we literally can smell the body odor ruminating from the screen. – John F.

High Life and Little Women (Yorick Le Saux)

Textured by pale glows and haunting claustrophobia, Claire Denis’ High Life, shot by Yorick Le Saux is comprised of contrasting compositions. Denis’ dismal dystopic vision is filled with lush gardens, hovering gloves without hands, newborn babies, bleeding faces, all communicating in some artificial medley floating in a prison. Beneath the pain and discomfort that these images conjure, a beauty breaks through, captured by patient close-up framing and infrequent moments of tenderness that express the ever-persistence of life. With all the violence, there is hope too, all gripped by an ambient silence. – Murphy K.

In Fabric (Ari Wegner)

The sumptuous, wild films of Peter Strickland represent such a distinct, unified vision that it’s somewhat of a shock the same cinematographer wasn’t behind all of them. After Nicholas D. Knowland shot Berberian Sound Studio and The Duke of Burgundy, the director brought on Lady Macbeth cinematographer Ari Wegner for his third feature and the results are stunning. In this giddily outlandish story of a killer dress, Wegner shoots all of the horror and hair-raising creepiness with a vibrant splash, but most important to the story, she also brings a relatable intimacy to the loneliness and frustration of Marianne Jean-Baptiste’s character with the warm tones on display. The cinematographer also has a bright future ahead, recently working on new films from Justin Kurzel and Jane Campion as well as one of our most-anticipated Sundance premieres, Janicza Bravo’s Zola. – Jordan R.

The Irishman (Rodrigo Prieto)

Cinematographers collaborating with Martin Scorsese wouldn’t expect a brisk assignment, but even a veteran of Rodrigo Prieto’s sort had plenty to handle with their latest, The Irishman. A 209-minute epic with numerous locations, multiple shooting formats, and, you’ve probably heard, distinct visual effects–it’s tiring just to think about. The cinematographer, who also shot The Wolf of Wall Street and Silence, is nevertheless casual in his assessment, and our interview at this year’s EnergaCAMERIMAGE covers its scope from both the most specific angle and on a gut level. – Nick N.

The Last Black Man in San Francisco (Adam Newport-Berra)

Not since the days of the cinema of Alfred Hitchcock has San Francisco been as radiant and gorgeously shot as Joe Talbot’s The Last Black Man in San Francisco. Sumptuously captured by burgeoning talent Adam Newport-Berra (Euphoria), the film honors the fabled city and its citizens with a distinctive visual flair, inundated with vivid colors that reflect on the faces of the actors and their surroundings to create a magnificent love letter that evokes the modern and yet nostalgic vision of the San Francisco. Through this lush cinematography and sense of momentum, a duality that is so uniquely a part of the city and the main characters themselves wondrously blossoms. – Margaret R.

The Lighthouse (Jarin Blaschke)

Whatever your response to Robert Eggers’ polarizing The Lighthouse, the visual bedrock established by director of photography Jarin Blaschke has been so consistent a point of praise it’s almost beside the point to note as much. Our review noted how the cinematographer “fluidly tracks and cranes his camera to follow the madness, often in unrelenting close-up,” comparing its tactile qualities to “old documentary footage, like something by Robert Flaherty, but with a hyper-reality to suit the genre tone.” Read our interview with the cinematographer here. – Nick N.

Long Day’s Journey Into Night (Yao Hung-i, Dong Jinsong, and David Chizallet)

In a sense, the presence of a film with a 51-minute long take in a best cinematography list is preordained. Yet Bi Gan’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night, as lensed by the team of Yao Hung-i, Dong Jinsong, and David Chizallet, is so much more than just a stunt, both in and out of its bravura second half. Rich and bold colors dominate throughout, embodying the noirish textures while mixing freely with the languorous yet rigorously controlled extended long shots. It is a film of ravishing, indelible images woven together, and the cinematography is more than up to the task. – Ryan S.

Midsommar (Pawel Pogorzelski)

A vibrant head-trip, Ari Aster’s Midsommar is a sun-dappled, subliminally sinister feast for the eyes that’ll make you long for the sweet release of darkness. What starts as a scenic Pagan fairytale with faintly murmuring malevolence, set against the idyllic summertime Swedish countryside, steadily progresses into a fully minacious and blooming vision of ritualized, sacrificial lore—one that doubles as an allegory for the search of family and what it means to find home in the wake of grief, loss, and the gaslighting toxicity of failed relationships. Something’s clearly amiss in this off-kilter version of utopia, as Pawel Pogorzelski’s pastel-bleached palette and dreamy mise-en-scène quickly become angelically oppressive. When coupled with the mutedly insidious harmony of the cult’s hippie-like communal culture, Midsommar’s uncanny aesthetic whimsicality only heightens the sense of hallucinatory danger lurking in this quietly threatening pastoral paradise. – Demi K.

Monos (Jasper Wolf)

Intentionally suffocating in its aesthetic, cinematographer Jasper Wolf’s camera moves with a fierceness as the characters’ unpredictable movements dictate what our eyes follow. In a few scenes, the HD image switches to the lo-fi digital camcorder their commander carries, creating a more confessional vibe of stark realism as he interrogates his soldiers and the breakdown of their group. As we’re wrung through this grueling journey, there a number of impressive visual touches from Landes. One striking single take is an overhead shot of a dead soldier’s belongings, carefully placed across a table. While one immediately thinks of a Wes Anderson-esque set-up, it turns grim as an entire life becomes reduced to a few items, being snapped up one-by-one by those who live on to fight a fight in which they are losing their mental and physical stamina. – Jordan R.

Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood (Robert Richardson)

Who better than notorious cinephile Quentin Tarantino to channel the conventions of the Golden Age of Hollywood into a revisionist fairytale? In a climate in which nostalgia films that pine for the past glory of Hollywood feel less acceptable, Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time.. in Hollywood balances an optimistic industry worldview with more realistic truths. Heat is translated into bright exteriors that convey this underlying tension while grasping the geographical scale of the city and its possibilities. Softly lit interiors displace common criticisms of Southern Californian superficiality by discovering the intimacy and comfort of spaces, whether they be cramped like a 1966 Cadillac Coup de Ville or vast like a Hollywood mansion. The allure is simply an inherent aspect of the locale – an irrevocable and authentic aspect of the city’s aura. As many have said in the past: L.A. always plays itself. Read our conversation with the cinematographer here. – Jason O.

Our Time (Diego Garcia)

Cinematographer Diego Garcia has had a busy couple of years, working with Apichatpong Weerasethakul on Cemetery of Splendor, shooting Paul Dano’s directorial debut Wildlife, and, most recently, sharing DP duties with Darius Khondji on Nicolas Winding Refn’s Amazon series Too Old to Die Young. Some of his finest work, however, is in this year’s Our Time, a meditation on infidelity and familial bonds from filmmaker Carlos Reygadas. Set in Tlaxcala, Mexico, Garcia turns the gorgeous landscapes and vistas of the Mexican countryside into expressionistic backdrops that emphasize the human drama at the film’s center and reflect the animalistic beauty of the fighting bulls that the film’s leads (Reygadas and Natalia López) raise in perpetuity. Even the interiors of the couple’s homestead appear as spacious canvases for the volatile emotions just beneath the surface of domesticity, light and darkness used as painterly expressions that say more about the interpersonal dynamics than the characters themselves are capable of expressing. – Kyle P.

Parasite (Hong Gyeong-Pyo)

When it comes to the meticulously storyboarded films of Bong Joon Ho, he found a perfect collaborator in cinematography with Hong Gyeong-Pyo (who also shot Mother and Snowpiercer, as well as another South Korean masterpiece, Burning). Together, they are able to execute his pristine vision with relentless momentum and, when it comes to Parasite, bring a specific vision to the class divide represented. The dark, cramped lower-class sub-basement(s) are juxtaposed with the elegance of the mansion, idyllically capturing the rays of the sun as they spill into light the luxury on display. When it comes to the furious finale, the cinematographer shows his true colors, being able to coherently capture the madness unfolding with an unwavering eye. We’ll also soon get to see another take on the cinematography as a black-and-white version of Parasite is premiering soon. – Jordan R.

Shadow (Zhao Xiaoding)

It could be said the Chinese historical drama is marked before Zhang Yimou and after Zhang Yimou. Transporting foreign audiences to his country’s long, often violent history in the most lush of compositions and stunning of action sequences–that is to say, sequences built on action as a concept of movement, shifting light, rustling fabric–and the tradition continues with Shadow. Key is his collaboration with cinematographer Zhao Xiaoding, with whom Zhang has worked since 2002’s monumental Hero. Read our interview with the cinematographer here. – Nick N.

The Souvenir (David Raedeker)

Joanna Hogg’s earlier films are striking in their picturesque abstractness as we sit in on conversations from a distance, but the ambition and warmth on display in The Souvenir makes this her greatest achievement. With the director developing ideas for this tale as early as 1988, based on her own filmmaking experiences, her formal rigor is matched with overwhelming intimately as if her camera is sneaking into scenes constructed of personal experiences. 16mm-styled footage is spliced in during an emotionally poignant scene as if Hogg wants to us to feel closer to the characters. From an evocative sex scene in Venice to a walk in the London countryside, the camera always finds itself in invigoratingly original positions, recalling Lucrecia Martel’s recent Zama in the sense that each new stunning shot will have one’s mind re-adjusting to what the framing might suggest for the characters. – Jordan R.

Transit (Hans Fromm)

There’s something to be said for unshowy yet masterful and confident cinematography, and one of the year’s finest examples was in Christian Petzold’s Transit. Shot by the director’s regular DP Hans Fromm, it is Petzold’s first film mostly in digital, and yet its use of deep blues and locked-down shots feels intensely evocative of a shooting style closer to Classical Hollywood, though filtered through the slippage of time and place of the film’s conceit. Its richness in both dark and light, its particular clipped use of 2.35:1, and its general strange fluidity vividly speak for themselves. – Ryan S.

Uncut Gems and Anima (Darius Khondji)

Since 2014’s Heaven Knows What, Josh and Benny Safdie have collaborated with acclaimed cinematographer Sean Price Williams in their grimy visualizations of contemporary New York City. For their latest cinematic grift, Uncut Gems, the Safdies have turned the clock back to the ancient past of 2012 and brought on the esteemed Darius Khondji as their new cinematographer. Khondji takes to the Safdies’ neon-streaked kineticism like a duck to water, pairing on-the-street voyeurism shot through telescopic lenses with tightly framed close-ups that emphasize the film’s innumerable shouting matches–the claustrophobic angles being analogous to the creditors steadily closing in on meshuggener Howard Ratner (Adam Sandler). Khondji’s compositions capture the early-2010s diamond district and its ephemera without distracting from the story’s frantic forward momentum, only stopping to fixate on the film’s titular opal and, of course, those shimmering, blinged-out Furbies. The concentration of Khondji (who also shot Paul Thomas Anderson’s remarkable Thom Yorke short Anima this year) amongst all the chaos is commendable as his camera strips bare the excess and reckless abandon of the post-recession hustle, where the only way up, at least in Howie’s crooked estimation, is down. – Kyle P.

The Wild Pear Tree (Gokhan Tiryaki)

It’s impossible to disentangle The Wild Pear Tree’s visceral grip from its visual language–the two coexist as one. Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s film is an impressionistic love letter to nature’s pensive beauty, and its bucolic tableaus fluidly harmonize with its compositional rhythms to offer a meditative ambiance that serves the film’s emotional, subliminal and stylistic needs. Every textured and ruminative frame is like a Van Gogh portrait-in-motion, as Ceylan’s languid pacing and DP Gokhan Tiryaki’s dreamy cinematography offer the sensory equivalent of dozing off on a hammock under the midday summer sun–drifting in and out, occasionally startled by the sound of a dog’s bark, but then lulled right back into a breezy reverie. As with many great impressionist works, the film intuitively threads the needle between the moody, the cerebral and the philosophical, and its subtle foregrounding of the seasons through Tiryaki’s verdant, autumnal and wintry hues capture the sweet sorrow of life’s cyclicality; change, growth, death, and rebirth. It’s a sentimental treatment of the outdoors as a vehicle for introspection, and as with Ari Aster’s Midsommar, there’s deference to man’s symbiotic relationship with Mother Nature that’s most hypnotically realized in an early scene set against the golden fall foliage. As two characters share a clandestine cigarette behind a massive tree trunk, everything begins to slow and quiet down, until time itself stands still–ceding the moment to the whispering leaves and the swaying breeze. – Demi K.