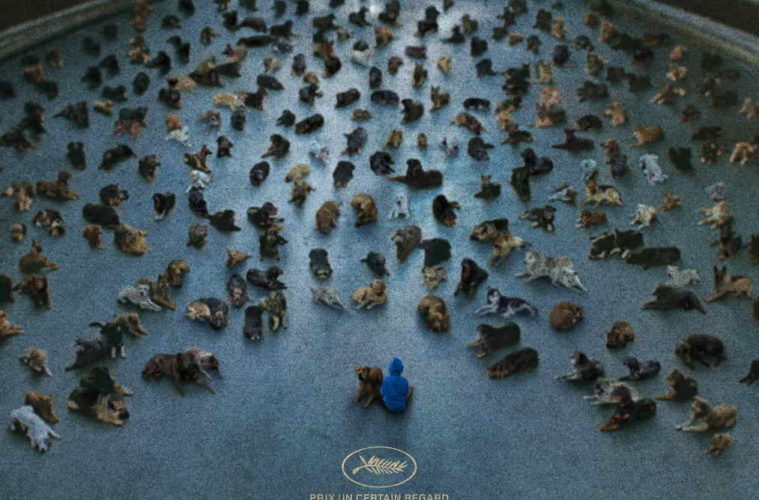

The darkest retelling of Homeward Bound imaginable, Kornél Mundruczó‘s Cannes-winning drama White God is equal parts a technically ambitious, but not entirely successful, tale of revolt and a fairly redundant coming-of-age story. The Hungarian drama opens on a desolate urban landscape as we’re introduced to the 13-year-old Lili (Zsófia Psotta), equipped with just a bicycle, a trumpet-filled backpack, and, as we soon learn, a pack of bloodthirsty mutts on her tail. How this striking imagery came to be won’t be fully realized until the third act, but Mundruczó feels the need to take away from the anticipation early on with this prologue.

Flashing back, we learn the young Lili, who is a burgeoning trumpet player in a youth orchestra, has been sent away to the home of her father, Daniel (Sandor Zsoter), to live for three months while her mother and her partner go away on business. For the extended excursion, she brings her best friend along: a mixed breed canine named Hagen, who disturbs both her father’s living situation and Lili’s music practice sessions. Due to new political laws putting pressure on her father to get rid of the animal, the canine is soon abandoned on the side of the road where he must fend for himself in an cruel environment.

As the narrative splits between these two storylines, we follow Lili’s tedious experiences with music school and rudimentary romance as she futilely attempts to track down her abandoned canine. Psotta, giving an admirable debut performance, imbues Lili with a convincing sense of determination and longing, but the story around her fails to bring much of interest to the table, particularly with a thin relationship with one of her classmates. These events are juxtaposed with the far more formally intriguing tale of Hagen’s journey in the treacherous urban landscape of Budapest.

As the dog encounters downtrodden street pals of the same species, they begin to band together to find scraps of food and company. Pursued by the local animal authorities, Hagen is captured, bought and sold in the style of L’argent (seemingly not the only Breeson influence here, as this acts as a more concise Au Hasard Balthazar, although invoking far less emotion). Despite a distractingly heavy misuse of shaky cam in certain sequences, often times Mundruczó and cinematographer Marcell Rév effectively place us directly into the dog’s point-of-view as it surrenders to vicious dogfighting and brutal abuse. However, the closer the separate human and canine narratives converge, the sillier and more muddled the film becomes.

On a purely visual level, as waves of canines flood the street and chaos ensues, the third act moderately glides by on the sheer logistics and execution of a mongrel revolt causing Budapest to go on lock down. However, subtler and more effective visual cues from the beginning, such as showing the cyclical process at Daniel’s meat-processing plant, give way to genre-heavy, blood-spattered allegories of the oppressed overcoming the oppressor. By the finale, what might have been a sharply-executed parable devolves into an all-too simplistic satire with its broad surface-level themes. Mundruczó’s focus is clearly going to the admittedly impressive execution, but White God lacks the narrative weight to leave an impact.

White God screened at Sundance Film Festival and opens on March 27.