There’s a scene about halfway into David Mackenzie’s Perfect Sense in which people become scavengers, rushing about eating everything in plain sight, from hands to flowers to peanut butter. When it’s all said and done, they have lost their ability to taste. It reads more visceral and engaging on the page than it comes across on the screen. Still, this is a unique world from the minds of Mackenzie and his writer Kim Fupz Aakeson, determined to find optimism in the most dire of science-fiction scenarios.

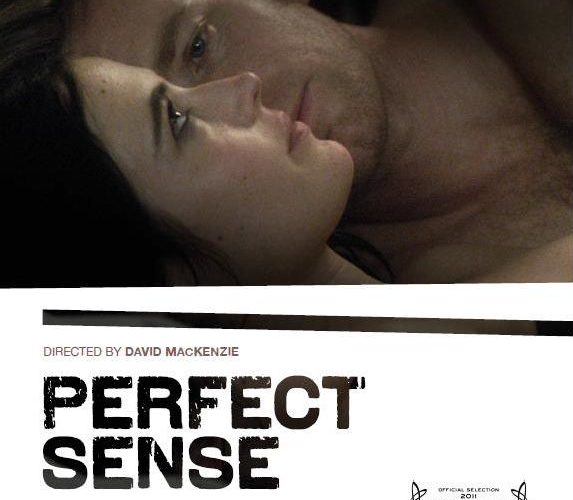

The scenario in question involves the rapid loss of sensory perceptions across the world: first smell, then taste and so on and so on. As this inexplicable pandemic spreads, a romance develops between a chef (Ewan McGregor) and a scientist (Eva Green) in Glasgow. The two stars have a deceivingly natural chemistry, both comfortable with rolling their bare bodies around on screen. Their first conversations are small and short, lacking much depth. Not that we need it. Their mutual attraction develops right in front of our eyes, though smiles and shrugs. No one would accuse McGregor of being an internal performer unless, of course, he’s falling in love. Nobody does it better.

That Mackenzie tries to illustrate the loss of smell through a medium that primarily relies on visuals is something to admire. Instead of exploring the physical effects of such a loss, he contextualizes what’s happening. Green’s Susan narrates over these explorations, describing memories forever lost without the ability to recall past smells through new smells. Once taste is lost, people stop going to Michael’s (McGregor) restaurant. Then, after some time, they return because, as Susan articulates, people need to go out, be waited on, criticize what they’re eating. People need to keep living life.

This positive outlook engulfs the entire film, staunchly separating itself from dystopias like Blindness. It’s closer to Children of Men in this way. Where that film finds hope in a child, Mackenzie’s film finds hope in the power of love.

It’s optimistic to a fault. Mackenzie invests fully in this non-sensory world of his. Surely, watching Michael lick his fingers and Susan sniff manure curiously will make as many people laugh as it will make cry. There’s an inherent goofiness to the premise, and, as with all science fiction, how much one suspends their disbelief will decide how much they invest themselves in those living in this world. The science is too thin to convert everybody. At the same time, it’s this stubborn simplicity that allows for incredibly interesting scenes, such as one in which Michael and Susan take a bath together after having lost their sense of smell and taste. They begin to eat the soap because of the texture of the bar. In another scene, Susan sits in a car and listens to the world. Layer after layer of sound builds, first cars then birds then laughter then screams, Susan coming to the terms with the fact that she will never hear the bustle of a city ever again. There’s no dialogue and only one shot on the actress, and it’s more than enough.

Mackenzie has always been an extremely confident filmmaker, pushing his narratives as far as they need to go, for better and worse. Spread is the darkest version of the playboy myth we’ll ever get, while Young Adam, which also starred McGregor, connects guilt and sex all under the plot line of a mysterious dead body. This film is refreshingly more friendly than those two, but no less ambitious. When the characters on screen can’t hear, we the audience can’t hear. When they can’t see, we can’t see.

And at the end there’s love, nothing else. It’s sappy, sure, but in keeping with the whole rest of the film. McGregor and Green and Mackenzie and Aakeson convinced me. Can they convince you?