Before we can even get on the record, before that most familiar robot warning of “This meeting is being recorded,” Frederick Elmes is swapping stories about Albert Brooks. After greeting me by name, he mentions a news piece I had written––a blurb about the recent Brooks documentary Defending My Life. He worked with Brooks some, he says, as a camera operator, goes on to speak generously and thoughtfully about the atmosphere the director cultivated and maintained on set, what that meant in turn to his work as a cinematographer, to the cast and crew more generally. I am sitting and grinning like an idiot, not unlike an ancillary Brooks character––maybe Bruno Kirby in Modern Romance. It strikes me that this moment represents Elmes’ approach to tending the moving image: careful research, a focus on listening, the sharing of ideas stemming from observation, and an immediate instinct for collaborative thinking.

To survey Elmes’ filmography is to take a Chutes and Ladders slip into American film history. Elmes graduated from NYU Tisch in 1972, moved to Los Angeles for fellowship work at the American Film Institute. Once there, he promptly began work in both the maverick cine-community of Cassavetes––a space that churned out, with pluckily non-Hollywood bite, A Woman Under the Influence (1974), The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (1976), Opening Night (1977)––as well as the experimental ambience of David Lynch, first with the short Amputee (1974) and then Eraserhead (1977). Elmes worked with Lynch on three more films, signaling a tendency for repeated collaboration that would hold for the films Elmes has done with Ang Lee (3) and Jim Jarmusch (6). Along the way are other spiky auteurs (Charlie Kaufmann, Todd Solondz), journeymen (J. Lee Thompson, Gary Nelson) theater directors working in film (Nicholas Hytner), actors directing movies (Christopher Reeves, John Turturro), as well as one-offs with American masters (Martha Coolidge, Charles Burnett). If the span of the work feels gobsmacking, I return to how Elmes characterizes the approach of Ang Lee, an artist familiar with artistic jumps, with mixing modes and tones: “The process is really the same.”

In advance of Metrograph’s most recent Filmcraft series, running through April 27, I spoke to Elmes over Zoom about the practical implications and conditions of cinematography. As we spoke, “collaboration” was the notion that kept surfacing in various shades and shapes. If the interview form is, perhaps, the means by which criticism can be co-conceived and co-questioned, there might be no better partner than Frederick Elmes, who makes the sharing of a vision an art form itself, renderable in moving images and the way light moves.

The Film Stage: How important is it, in terms of working on a set, for the crew to be at ease, for the actors to be at ease?

Frederick Elmes: I think it’s paramount. It’s really, really important. And that tone is mostly set by the director. It really is set by the person in charge, the kind of situation that they feel most comfortable working in. I just worked on a film with Jim Jarmusch and he’s sort of a long-time friend and collaborator and, you know, he likes certain things. He really wants the set to be quiet, to be a sheltered place. There’s not a lot of people standing around. Everybody gets to do what they need to do, but they don’t need to be standing there in front of the actors in those moments when you’re shooting. It really starts at the top with the director––or the producer, if the producer’s on set. It’s how they handle and work with the director, how they handle and work with me, and then the tone that I set in order to keep it all going.

Do you find that these abstract qualities like the “tone” or “voice” of a film stem in some way from that environment on set?

I think so; I think it’s all related. I mean, it’s not to say that chaos doesn’t breed some success. The energy comes in. I had the pleasure of working with John Cassavetes on some films years ago. And he kind of ran on nervous energy, coffee, and cigarettes constantly. The energy had to be up. He was a very charismatic person, so he could inspire that in anyone. He would bring you up and then beat you down, get the performance he wanted, and then apologize for taking advantage. You know, many of the actors were not actors––they were not seasoned people––but he could really manipulate a situation. He could manipulate a situation where the crew worked better, where somehow the camera assistant got the focus pull on the next take because they’d been slightly verbally abused by him. But he always apologized. He always came back and said, “Look, I wanted it to be this way and I had to get it.” Whatever it took to make that happen.

Did he know what he was doing, or was it just how the work came out?

No, he knew––he knew exactly. He was completely in control. I mean, he was a seasoned actor. He could do anything. He just looked at you and commanded the space. The same way that Albert does. I mean, Albert just took over; he just enveloped the whole room. Things had to go his way. And that’s the way he was most comfortable being there. I think that it’s important for a director to have that command of a situation because it shows that there’s a confidence level there. And it’s not as though they have to shout to do this; they just have to emanate confidence and it becomes infectious. It helps everyone get the job done. Certainly paying compliments and saying “thank you” is all part of that. And some people don’t, you know. It’s a funny sort of business in that way.

Is it about being the authority on the film they’re making? As long as the director knows the most about the film they want to make, and if they can spread that out, maybe that’s a way to be an authority without being authoritative?

Right, without being a dictator, which, you know, is just obnoxious some of the time. But certainly to be the authority, to be the person with the knowledge and willing to disseminate. Not keeping secrets. Willing to help everybody do better at what they do somehow, yet owning the movie, owning the situation completely.

Can you think of other people who work a different way, where the collaboration feels itself a little less top-down?

I think everybody does it differently. I’m a graduate of NYU Tisch and many, many years ago they had a celebration for Ang Lee, who I’ve worked with a couple of times. He’s a completely different sort of director. He kind of commands the space by saying nothing. You need to come to him for the information and he always gives you some clue as to what he wants without saying too specifically. He leaves it to your interpretation, yet he still holds the information. He still is running the movie, even though he does it with the fewest words of any director I’ve ever worked with.

I rewatched Hulk last night, which feels a little like an apotheosis in a line of very different kinds of movies. Does it feel that way? When you set out on a new project with Ang, are you both thinking something like, “We’re gonna do this kind of movie this time, it’s gonna look like this, it’s gonna move like this?“

You know, that’s funny. The process is really the same. The process with Ang is really the same. I met him on The Ice Storm and he had just done Sense and Sensibility, which is a completely different sort of story, just totally different. As many of his films are––one to the next. The process of researching the early ’70s in New Canaan, Connecticut was really, really specific. He was in Taiwan at that point. He was not in touch with it. I became––along with some of the actors who were there, who were alive in the ’70s––became part of filling in that research, but certainly it was the art department that brought together the ’70s, you know, 25 years after the fact for us.

And that was really important to Ang, to have all that information at his fingertips––figuring out what exactly was the style of clothing, what exactly were the cars in use. Yet he did it in the most sort of gentle way. There was always pressure there to do it, to answer the question, and he did it in the most easy, comfortable way possible. Yet it got done.

Frederick Elmes and Ang Lee on the set of The Ice Storm

Especially with something like The Ice Storm, how important is that research, spending that time with photorealism as a movement and tradition?

That was part of our research package. Those kinds of images that look so real, they could have been a photograph––imitating exactly the light of a crisp sunny day, on a sidewalk. We went and looked at the paintings. We went to galleries and we found things and we found examples. We said, “Yes, in an ideal world, New Canaan, Connecticut will look like this in our movie.” And it was the same with Ride with the Devil, which was the Civil War, and the same with Hulk, which was who-knows-when, you know?

Sort of a painting emerging from comic books?

Comic books, at the root of it, and that whole issue of how to divide the frame and when and how to make multiple images that work possibly together. We did some research. We shot some things. We cut some footage and looked at things to try to find it before we even started shooting.

It’s amazing to watch those split-screens, which is sometimes with three different shots, right? Three different images. Was that exciting? Was that challenging on set, in terms of communicating to the actors as well?

It wasn’t simultaneous for the actor; most of those effects were either augmented, you know, visually. So they were complicated, and they all had individual needs. And we had to hope that the sync would work between them if you showed them simultaneously. Really complicated. But with the help of ILM, they really never said no. They always said, “Yes, we’ll figure this out somehow.” So that was a great support system for us.

A whole different way, maybe, but the same sort of painting with the camera.

Mmm-hmm. Those little close-ups of lichen on rocks. Ang was obsessed about those. We went to such ends to photograph lichen. Lichen doesn’t transfer well. It doesn’t grow, really, anywhere. I’ve learned a lot about lichen. You’ve got to photograph it out there on the rock or the lawn, wherever it is, and if you find that special blue one, you just better really work it because you’re never gonna see it again. No matter where it is, get the camera in there. So that’s what we did. And they became part of the film, that element of the film.

Frederick Elmes and Ang Lee on the set of Hulk

How often do you find yourself working on a film where you have to find the smallest thing, where you’re working with someone to find the smallest detail amid this huge story?

I think that happens. Sometimes those are the little hooks that might make a whole scene function. Usually they’re between a director and the actors, but sometimes it’s for me. It’s like saying, “I know that I can crack the feeling of this first act if I could just figure out how to do this one scene and get that right in my head at least.” I would go to sleep at night thinking about it and wake up in the morning thinking about it until I figured out some little key that I could hold on to.

I was thinking about it in terms of Valley Girl and that film’s conception of color. How did you and Martha Coolidge go about tracking that?

That was fun. We did that right from the start; that was something that she and I came up with together. It’s a Romeo and Juliet story. It’s the guy from Hollywood and the girl from the Valley. And in Los Angeles, I mean, they’re on different sides of a mountain as it happens, but we could exaggerate that difference––particularly with the advent of Frank Zappa and the whole Vals movement that was happening. At that moment, Hollywood is pretty gritty. This guy hangs out in rock ‘n’ roll clubs and it’s kind of harsh. The light is harsh and the music is loud, there’s a lot of darkness, there’s some flashing lights, there’s some pretty strong colors. And the Valley we made just the opposite. We made it sort of soft interiors in pastel-colored living rooms with the Valley kids wearing pastel t-shirts, much softer colors, and just kind of kept them very different visually in that way. It helped Martha and I ground ourselves in the costume decisions, in the colors of cars and sets and lighting situations. It was really a hoot to do that film.

There’s a very different use of color in the two films you chose to accompany yours in the series, Cries and Whispers and Tess.

Very different. When DeWitt from the Metrograph said, “Okay, now we just need you to choose a couple of films as your influences.” I thought, “No problem. I’ve got this director, I’ve got that director, I can do this.” And then I sat down and tried and it would have been much easier if they’d asked for 10. 10, 15 I can do. Two––that’s crazy. So they stand for a lot in my head because of the directors. Those were the influential directors: Roman Polanski in his early films for sure, and Ingmar Bergman and Sven Nykvist together were such a great pair. I couldn’t stop imitating Sven Nykvist.

How did that imitation start? How did you go about it?

I would look at the light. How does he get this soft, naturalistic light? There’s nothing theatrical about it. It’s dark, it’s moody when it has to be, it’s lighter when it has to be, yet it’s always so soft and becoming––it’s very gentle. And so I kind of analyzed how the heck he did it. Then I would bring that to the next film I was shooting in any capacity, you know, whether it was an educational film or a student film or whatever––wherever I was at.

Do you remember the first time you were watching a movie and you saw cinematography at work, where it felt like something was being done?

I mean, I think it unfolded over years. I think that certainly, with Polanski in early films like Knife in the Water and Repulsion and Rosemary’s Baby. You know, the severeness of it, the severeness of the angle of the contrast of lighting––those were interesting to me. They stood out in the same way, but completely differently from the light and the feeling of Bergman films. I put myself through college pretty much as a projectionist. And I got to see a lot of films that I normally wouldn’t have come across, separate from the Hollywood movies that were showing all over where I grew up. I was projecting Fellini and Antonioni and De Sica films on a regular basis, and it gave me this understanding, this whole other perspective of movies and storytelling that I didn’t get from childhood or teenage years.

And such a specific vantage point: from the booth.

And from the booth. Which meant, of course, there were certain parts of the film when I was doing a changeover that I would always miss, because then you had to rewind the film reel. Yet I saw the same film several times. I stayed glued to the window because sometimes it was reading subtitles from a distance. But it was wonderful. It was so eye-opening to be exposed to that broad spectrum of films in an art house sort of cinema. And then somehow John Cassavetes folded into that. Shadows and Faces, I got to see and just digest as being so very different from other things I was seeing in movie theaters. I wanted more, you know? And then I met him and I got to work with him. So that was such a treat.

The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (1976)

With The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, you’re listed as Camera Operator, but you also did the lighting, is that right?

Well, yeah. You know, yes––I did all of it. I mean, John loved to hire student workers on his films. He kind of detested making a Hollywood-like film with the structured crew and all the trappings that came with it. So on Chinese Bookie we had, like, a cinemobile, a one-truck show that had almost all the equipment in it. We had the lights, the cameras, even though they were old lights and old cameras. And we were all, I don’t know, under 25 years of age? The crew was pretty young and pretty inexperienced. And John said, “That’s all I need. You know? You’re the ones that can experiment with it. You can help me make this film.”

And even though he certainly had been there before––he’d seen it all, he’d seen films made in so many different ways, big and small––he really wanted to film this way. And he would finance Chinese Bookie or whatever film by the success of his previous film and, like, mortgaging the house again. I mean, that’s kind of what he would do every time to get his film made: take a good acting job and then be able to start up his own film.

And then you came back for Opening Night?

John had asked me to come and be the operator on Opening Night, one of two operators basically, but John wouldn’t give anyone a credit. There was no “director of photography” credit on his film. I mean, I think the producer actually took it on one or two of the films just because he could. It was really about John creating this community, and I happened to be the oldest one and had done some lighting, basically. So when it came to the stage lighting, I was familiar with stuff. And I think that the gaffer’s credit was “In Charge of Lighting,” you know, and he had never done it before. So luckily we were good friends, and it worked out.

Does it seem like there could be a tyranny of job roles without that sort of improvisation? That it’s important to have a plan, but that there’s an appealing freedom to that kind of collaboration?

Yeah, there is. And I think that’s what John was sort of overjoyed at: that he could get it his way. He could create this company of people that he trusted who would listen and who wanted––really wanted––to be there. Cause we certainly weren’t getting paid much. We wanted to do this, to be part of something that he was part of. And I think that that’s what drew everyone: because we came from all different directions, not necessarily film backgrounds, but theater and, you know, here’s somebody who wants to act and so on. He would collect us, you know? And luckily I was at the AFI at that moment. And he was editing a film. He asked me if I wanted to join the next one. I said, “God, yeah.” You know, I mean, why not work together again?

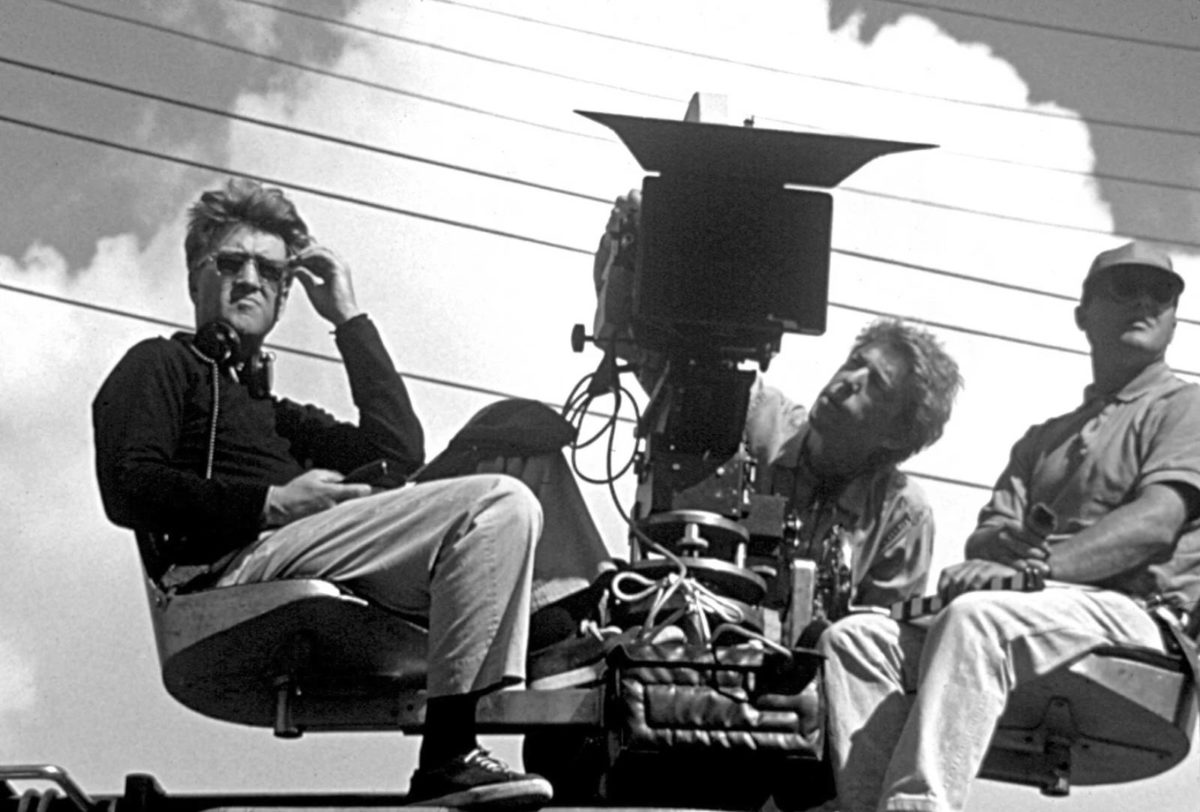

On the set of Wild at Heart

Thinking about Cassavetes and this notion of making films freely: that moment in Wild at Heart, the one where all they hear is bad news on the radio and then they find the heavy metal… it seems like it’s such a moment of finding freedom, of the camera really responding ecstatically.

I hoped we would get that right. It was kind of a critical place in the story and we needed to show them on the road and on the run, yet also to find something that was, I don’t know, positive and satisfying for just a minute. That’s something that David Lynch and I were always thinking about: “How the heck do you do this?” When it came to shooting it, it was like, “Okay, well, we shot the morning stuff and now we’ve gone over in the afternoon and you’ve got a couple of hours to shoot this.” We needed a little more time to plan this out! But we had found the spot by the side of the road where we knew the sun would set. So if we parked the crane here, we’d be in about the right neighborhood and the car could pull off and all that. We found that.

But I mean: we were out in the plains of Texas somewhere. There weren’t a lot of resources for us. We had our meager bunch of equipment and a small crane that day. But the fact is: we shot the two of them at the gas station filling up and pulling out, and then we raced over to the next location and tried to get it in time. If there’d been clouds on the horizon, I don’t know if we ever could have gone back. We just kind of would have accepted it. But it all fell into place for us.

It feels like pure love.

I mean, it’s everything, you know; it’s everything. It’s the place we chose. It’s her costume and the same red color as the bricks on the wall behind them. And the weather was great, the crane was just tall enough and the music swells and it all sort of takes off. So that’s what you hope for. You hope that you get a couple of those in each movie.

Filmcraft: Frederick Elmes takes place at Metrograph through April 27.