In Carlos Reygadas‘ Post Tenebras Lux, a Latin phrase which translates roughly to “light after darkness,” the Mexican filmmaker continues to channel his trademark cerebral cinematic tendencies into a haunting parable about life and death, Heaven and Hell and the nature of our dreams. Similarly surreal to Leos Carax’s fellow Cannes competitor Holy Motors but completely different in tone and style, Reygadas attempts to infuse a deceptively simple narrative with metaphorical subtext that serves as an insight into the characters’ everyday struggles. Relying heavily on powerful imagery, Reygadas elicits a mood of unpredictably that touches upon themes found in his past films. For some it may be too bizarre, meandering and disturbing to swallow, while those who approach with it an open mind will find some satisfying morsels of cinematic indulgence.

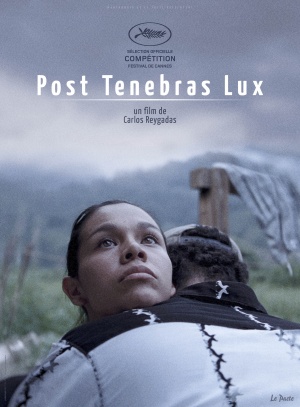

We begin with a breathtaking opening, a constantly-moving steadicam shot of a carefree little girl walking through a field as cattle, horses and dogs circle around her in the background. As the sun begins to settle, the sound of an approaching storm ominously reverberate along with flashes of lighting over the opening title. This is followed by the appearance of an Uncle Boonmee-style glowing red demon, carrying a toolbox, wandering aimlessly through the house of the film’s most central characters. That is a wealthy young couple (Adolfo Jimenez Castro and Nathalia Acevedo) who, along with their two kids, live in a modern abode in the middle of nowhere. The plot criss-crosses between their collapsing relationship and random vignettes, such as a group of teens playing rugby or a hellish orgy in a sauna.

It’s worth noting that the film is shot in a square aspect ratio and oftentimes Reygadas employes a tilt shift lens to distort the image naturally in camera without post-production effects. The result of using a tilt shift lens is that the periphery of the frame is constantly out of focus so as characters or animals move in and out of shots, there is a doubling effect. This technique, while somewhat interesting at first, becomes obnoxiously over-used and loses much of its visual impact. Still, Reygadas has a natural eye for composing shots in ways that feel completely unique while putting subjects in front of the camera that you would least expect.

The biggest problem with Post Tenebras Lux, unfortunately, is the disconnected narrative of the couple, a through-line that barely holds attention due in large part to the amateur performances on display. Reygadas would have been better off steering in the direction of his previous film, the The Tree of Life-esque Silent Light, instead of trying to focus on the couple’s turmoil. Also, there are some scenes of dog brutality that feel completely unnecessary and superfluous, reading as the kind of shock value that leaves a bad taste in your mouth. Despite all that, Post Tenebras Lux is still a unique piece of cinema that, while probably the least accessible of all of Reygadas’ films, offers up the occasional moment of wonder, making it worth seeking out for those cinephiles fascinated by the out of the ordinary.