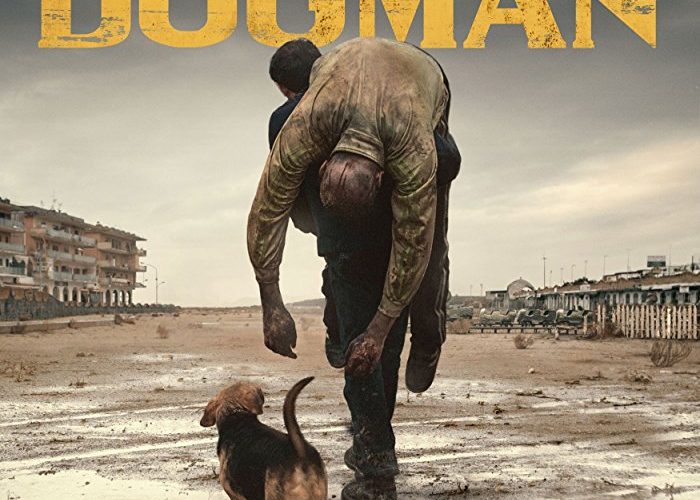

Matteo Garrone’s Dogman features many of the same themes and motifs as his 2002 film, The Embalmer. Its grisly narrative is again loosely based on real events drawn from the news, it is again set in a run-down coastal suburb in southern Italy, and it again focuses on the skewed power dynamics between two male characters, one tall and the other short. The metaphorical slant, however, is even more pronounced this time around. By depriving their David and Goliath story of geographical and chronological specificity – both setting and time period are kept purposely vague – Garrone and his co-writers, Ugo Chiti and Massimo Gaudisio, have also stripped the film of any genuine social relevance. The result is a philosophically bankrupt, if effectively constructed, spectacle of violence.

The two protagonists are Marcello (Marcello Fonte), a literal and figurative little man who owns a dog grooming salon, and Simone (Edoardo Pesce), a hulking thug and rampant coke fiend who terrorizes the entire neighborhood, with Marcello as his victim of choice. The meaning of this film’s title, which is also the nonsensical name of Marcello’s salon, doesn’t take long to emerge: no matter how much abuse Marcello suffers at Simone’s hands – be it constantly hustling him for cocaine, forcing him to participate in a robbery and then swindling him of his share, or landing him in jail for a year – Marcello’s loyalty and friendship is unswerving. Simone is not his owner in any figurative way, but the film’s symbolism is generally pretty confused.

Take Marcello’s profession. Are the dogs locked up in cages representative of how Marcello and the others are entrapped by Simone’s violence, or is the sight of Marcello brushing their hair, filing their claws, and giving them baths a metaphor for their servility? In other words: on which side of the equation do the dogs belong in this heavy-handed allegory about the weak and strong in society? Perhaps the point is that it’s a dog-eat-dog world, though that’s unlikely, given that, in Italian, the expression is “dog doesn’t eat dog.” Regardless, the grooming scenes, which feature a wide variety of breeds in variously adorable poses, are excellent, providing some of the film’s exceedingly rare moments of charm.

The way DP Nicolai Brüel shoots the dilapidated housing blocks along the beach, often in imposingly extreme long shots that render Marcello even smaller and more vulnerable, makes the whole area resemble a war zone. That the mafia should be responsible for this disgraceful panorama is assumed by default. But unlike in Gomorra, and even The Embalmer, Garrone dedicates no time to the macro dimension. Instead, the misery on display merely serves as a scenic backdrop for his fatuous meditation on the nature of man – and man alone, given that women don’t figure in Dogman‘s state of nature, except as a pure counterpart.

Garrone’s prowess as a director is still undeniable, and as far as nasty, gripping brutality goes, Dogman certainly delivers. If you’re looking for pulpy violence, you won’t be disappointed. Just don’t expend too much thought over what it’s all supposed to mean.

Dogman premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and opens on April 12. Find more of our festival coverage here.