Being an embedded photojournalist is a concept I cannot quite wrap my head around. To willingly go into a war zone and risk your life to get a shot, not for plaudits, but to educate the world about atrocities we’d rather turn a blind eye towards? It’s one thing to do it in a place where an errant bullet aimed at a rebel or infidel could miss its target and hit you instead and a whole other at present when terrorist organizations like ISIS seek any western face they can to behead on TV and reinforce their extremist rhetoric. To do so with a spouse, children, and people who love you back home takes a level of courage impossible for me to measure. And despite its selfless quest to eradicate ignorance, one needs plenty of ego too.

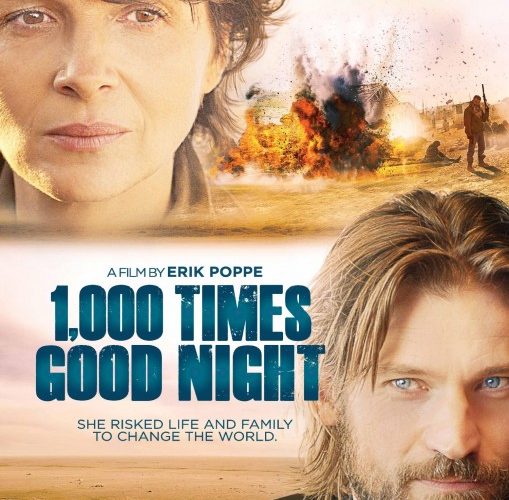

This is exactly the person screenwriter Harald Rosenløw-Eeg and director Erik Poppe have crafted via Juliette Binoche‘s Rebecca in 1,000 Times Goodnight. Here’s a woman who has been photographing conflict areas for years with the generous support of her husband Marcus (Nikolaj Coster-Waldau) until the moment he and their daughters Steph (Lauryn Canny) and Lisa (Adrianna Cramer Curtis) dreaded arrives. Rebecca is been caught in the wake of a suicide bomber—bruised, battered, cut, and punctured through the lung. While her injuries are physical and luckily healable with time, those endured by Marcus and the girls are anything but. For them the issue has finally moved from possibility to reality and they have reached their mental and emotional breaking points. Every time she leaves means they must once again brace themselves for the nightmare they’ve only just narrowly escaped.

Poppe delivers an exhilarating opening scene to show these stakes in a way I wasn’t expecting. You read the synopsis and think about the emotionally wrought familial drama to come, not the cause for its strife. Heck, you don’t even think about it in the moment because Rebecca is simply a photographer shrouded in Muslim garments at a funeral—she’s not a soldier. She snaps photos of mourners, the ceremony, and the palpable pain seeping into the desert air around her. And then we realize what’s happening isn’t quite as we thought. It’s a funeral, but not for the presently deceased. No, Rebecca has entered the company of an Islamic sect preparing for an attack. She documents a young woman strapping on a bomb vest and then begs to enter the car that could potentially serve as her tomb.

Shot with a gorgeous eye by John Christian Rosenlund, the filmmakers aren’t afraid of lens flare or overexposure to add an ethereal beauty to horrific circumstances of which we’re bracing ourselves for impact. There are surreal glimpses of Rebecca drowning upside down in a pool of water cut with memories of her family until she opens her eyes on Marcus. From the nightmarish visuals of a war torn town engulfed in flames to the stark white sterility of a hospital, we witness the birth of a second chance. It may appear ceremonial at first since we can see the passion in Binoche’s face to leave again, but arriving home to her girls and the candid declaration that her husband can’t do it anymore makes the situation sink in. Rebecca must make a choice: work or family.

From here comes the effective drama we’ve expected, one populated by an easy-going father willing to forget the suffering in order to keep his family together and a compromising mother ready to take a new step in her career to ensure she’s able to watch her daughters grow up. As for the children: there’s the precocious Lisa still too young to fully grasp the gravity of what Mom does and the hurting Steph who as of yet doesn’t quite understand why Mom cares more about other people’s children than her own. A carefully placed school assignment on Africa assists the eldest sibling to target her anger and realize the importance of Rebecca’s occupation, but it also provides a “Sophie’s Choice” of sorts that’s able to rock the Thomas family to its core once more.

There’s definitely a political agenda at play with a hard sell about the censorship of our world’s atrocities and the governments too afraid to tell their publics the truth, but it never quite pushes into preaching territory. It’s there because it’s what Rebecca believes and we must comprehend its impact on her decisions. Without seeing her ferocity we wouldn’t be able to accept what she eventually does as fact because to the layperson a choice between protecting your child and leaving her to risk your own death is easy. In fact, it’s pretty easy for Rebecca too—just not what we’d guess. And the ramifications of what happens pours down into a sequence as powerfully sad as that of Leonardo DiCaprio drunkenly taking his son away towards the end of The Wolf of Wall Street.

Coster-Waldau adds a perfectly balanced sensitivity and strength in the face of everything and Canny’s youthful, emotional confusion has the goods to make sure her mother’s choices are as difficult as possible. As a result, Binoche delivers one of the best performances of the year. From stoic professionalism on the job to quivering lips of a mother knowing the pain she’s caused loved ones to the growing instability of a mindset she prided herself on to stay objective at war, her Rebecca drags herself through the wringer. Her trajectory isn’t tied neatly in a bow either, but instead ends exactly where someone with her convictions should. The film is less about “fixing” anything and more about showing the same unfiltered suffering her photos capture international within the microcosm of a domestic home of which we can all relate.

1,000 Times Goodnight is now in limited release.