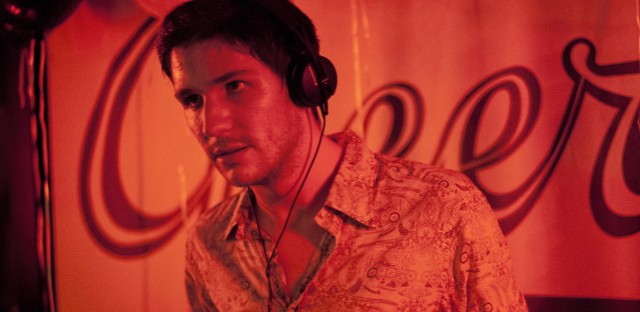

It begins with a dark night in the woods and the occasional sight of a half-complete face or full-figure silhouette, such impressions stemming only from pale moonlight. These figures are followed over multiple shots, and what little can be discerned herein is quietly expanded upon with some illumination — soft, spotty, and artificial, but with an expressive quality that lets us know we’re outside all boundaries of normal civilization. After the first real exchange of dialogue comes the first true close-up: not of a face, but hands, this Bressonian gesture guiding the camera’s vision from a turntable to a stack of records to one record in particular, that special item an unidentifiable young man wishes to hear. The music starts, and, as if it is only through these sounds that the world can expand past this hermetic set, a cut proclaims “let there be light” — merely daylight to them, sure, yet the first thing through which “them” could be identified as more than just a shape. Without a spinning record, they are nothing.

This is how we enter Eden, the fourth film by Mia Hansen-Løve. In allowing her brother and co-writer Sven Hansen-Løve to take the autobiographical Bildungsroman angle explored so fruitfully in Goodbye First Love, she’s found herself the commercial surge experienced by French House music circa the mid-90s — Daft Punk, key figures in this picture, are the most obvious point of reference — here experienced through Paul (Félix de Givry), an ambitious and, over the course of 18 years, never-aging DJ. (Whether or not it’s intentional, an ex-flame telling him, “It’s so crazy that you haven’t changed” nevertheless elicited big laughs at the NYFF screening.) With its particularly male-centric angle and supposedly necessary expansion of scope, those familiar with her work might already detect a shift. Her first three features worked in smaller units of character narrative incident, driven mostly by parent-child / husband-wife conflicts or broken hearts; fair evidence of her considerable gifts notwithstanding, the decades-long chronicle of a cultural revolution is, to some minds, reason for concern.

Fear not. Rather than 131 minutes of a throbbing soundtrack complemented by extravagant club-lighting schemes, Eden is indeed un film de Mia Hansen-Løve: its aesthetic dressings are both spare and precise; its language, as both written and performed, is quiet (even the glut of music isn’t played to high-decibel levels); and its formalism is, by certain definitions, “low-key,” the camera-eye acting almost exclusively as a means of digging out characters’ psychological processes via captured glances and gestures. The cohesion just isn’t immediate at first. Though devotees should hardly be bored by her oeuvre’s central tenets, Eden’s structural predilections — in which three or four years can pass with a single cut, a single title card, and only a few more facial hairs to mark the difference — initially carries with it some sense of imbalance.

There’s a push-pull between this man’s journey and a widespread knowledge of what’s happening on its periphery — at points, I just wish to hear a song instead of see how a beat gets chosen. If great music is being made and, on Paul’s part, broadcast to the masses, what of his fling with an American girl (Greta Gerwig, more or less making a cameo) or arguments with friends? When does this begin to feel like it really matters? The picture’s equal-sized devotion to both the microcosmic intricacies of person-to-person interactions and necessitated grapple with a macro-level new wave are somewhat undercut at either angle, as if she’d failed to find a precise point of focus for immediate or deeply felt sensations. Thus ensues a struggle to extend the experience past general appreciation, Hansen-Løve’s perceptible confidence in these images — rarely does a filmmaker so obstinately avoid indulging in the club atmosphere, instead keeping deliberate distance from this action — and the subtleties of de Givry’s turn — credit to a newcomer who can make irrelevant the fact that he looks identical from one decade to the next — notwithstanding.

Only in retrospect could I understand Eden‘s careful delineation of temporal, emotional, and geographic properties: it wasn’t that the Hansen-Løve siblings had fallen victim to imbalance, but that their taste for structure — or (deep breath) their taste for the delineation of temporal, emotional, and geographic properties — necessitated the full picture in order to be comprehended with even the slightest of critical responsibility. A mirroring of dialogue, relationship dynamics, narrative benchmarks, Paul’s reaction to each, and formal tics create the impression that his experiences are ours, too, as if a personal perception of time has mutated into a collective experience. Key to this perceptive construction is one scene in particular, Eden’s lynchpin and a display every viewer is assured to recall weeks, even months down the line: circa 2001, the picture’s protagonists journey to the United States, a rush of images and cross-fades (specifically centered on an outdoor MoMA performance) set to Daft Punk’s “One More Time.” For one brief, ecstatic segment, the film’s players and our culture’s pieces are made whole — images of the masses dancing with one another fade into each other so frequently that they momentarily weave their own visual web, only to be broken by the DJ to whom Hansen-Løve’s camera stays locked longest and with the most devotion.

One critical instinct insists that Eden concerns itself with too long a period of time, too varied a slate of experiences, too large a spectrum of feelings, too varied a set of gestures, and too wide a phenomenon to be contained so fully in one dialogue-free montage. Is containment even needed? Considering how strong the cumulative experience proves, no. I suppose it’s fine to appreciate these few minutes as “merely” some of the most overwhelming cinema offered this year. But another tells me to approach these images as if they were the song in question: concede all intellectual pretenses, let it flow through the brain, and embrace this brisk run through time, experiences, feelings, gestures, and phenomenon as emotions dictate. Eden isn’t cold — it’s only asking that we associate on a path toward clarity.

From this point forward, each ensuing scene thus operates as both a next step and crystallization of what’s come before, and so absorbing does Paul’s story become that the bifurcated structure — not only an established staple of Hansen-Løve’s films, but something announced by this picture’s opening card, “Part One: Paradise” — is forgotten entirely before reaching “Part Two: Lost in Music.” That the widespread expectation instilled by such an ominous subtitle is never actually fulfilled would demonstrate how deftly the sibling scribes have been steering action up to this point. Rather than a fall we’re now so accustomed to, the unusually casual nature of Paul’s decline — a few too many drugs snorted, a few too many dollars spent, a couple of loved ones gone — only serves to softly underline that there was never much of a rise. Dispense all thoughts regarding the standard music biopic; instead consider a place alongside Inside Llewyn Davis or, with regard to its sudden temporal leaps, David Chase’s Not Fade Away, great pictures about perpetually being on the cusp of something transcendent and never, ever reaching it.

Although those who’ve seen both can then surmise where this story concludes, I wish not to say too much of Eden’s final scene, hoping that the intended imprint can be preserved to its fullest extent. It would, however, be remiss to make no acknowledgement of our last moments with Paul: a discomfiting sound-text-image superimposition used to suggest, in total consistency with all that’s come before, that nothing genuinely exists here or now, but only through an internalized rhythm one makes for themselves. Its particular presentation carries an elegiac air — one so weighty that I’ve yet to shake it a week on — but I like to think a hopeful idea also rests within: that we’ve failed ourselves doesn’t mean we can’t find hope in others, and that we’ve fumbled while getting here doesn’t forever preclude us from living with a little bit of dignity. Light at the opening, dark at the closing, music forever.

Eden is playing at NYFF and will be released in the spring of 2015, courtesy of Broad Green Pictures.