Filipino writer, director, editor, production designer, and cinematographer Lav Diaz is over 25 features deep into a three-decade-long career, and he continues to one-up himself. With Magellan––a biopic that couldn’t be less biopic, and one of the year’s greatest surprises––he enters new territory once again, this time working outside of the microbudget Filipino system he’d fashioned for himself, which has allowed him to crank through lengthy, meditative, experimental features that stretch upwards of ten-and-a-half hours and employ intimate crews the likes of which Hollywood has never known.

With a major A-lister onboard in the title role in Gael García Bernal and all-trusting Portuguese and Spanish producing stars behind him, Diaz welds his taste for the avant-garde with an uncharacteristically narrative approach that’s garnering more global attention than most of his past work, regardless of how strong it may have been. On the eve of its U.S. release, I sat down to talk with him about telling the oft-celebrated colonizer’s story in a way only he could, Magellan’s impact on the Philippines today, crafting cinema in new ways, and his fresh artistic processes.

The Film Stage: You’ve got five major credits on the film that I want to talk about, starting with the screenplay. What inspired you to write a film about Magellan in the first place?

Lav Diaz: Well, if you’re Filipino and you want to understand your history—not just the story, but why we are like this now as Filipinos—Magellan was one of the key figures of that. He was the first European, supposedly, to set foot in the country, and he started all this conversion. 80% of the Philippines is Catholic and it started with one. It’s a good subject for summoning the Filipino soul, so to speak.

Is that still true? That 80% of the country is Catholic?

Yes. And in fact, the icon—the Santo Niño icon that they brought, that he gave as a gift to the wife in the film—it’s a real thing. It’s still the biggest icon in the country at the moment, this Child Jesus icon. So the impact of Magellan has stayed with us, of course.

How long did it take you to write the screenplay?

I wrote a different piece when we presented it to get funding. I sent the Beatriz story. I invented the personal story about Beatriz, the wife of Magellan. There’s little mention of her in anything you see. Books, Google, only four to five lines, and that’s it. She was the wife of Magellan. She was young, maybe 19. They had two sons. She was the daughter of Diogo Barbosa, one of the best friends of Magellan. That’s the only information. So, for me, it was the best part of it: I can invent the story of Beatriz. But, over the course of my investigation and research, the most overwhelming thing is, of course, the discourse on colonization, and I had to go back to Magellan for that.

You’re listed as the production designer as well. What does that look like for you? Is that primarily something you’re doing in pre-production, or are you always working on it throughout the shoot?

Location-hunting, doing the research. I’m already imagining the design of the late 15th century, the 16th century. Magellan was very much a part of things, from the slave trade to all the activities of Afonso de Albuquerque when Magellan was a young warrior. His ambition overwhelming him. I was imagining the whole universe, the look, the smell, the feel, all the things—the design.

Do you draw out designs for your team to implement?

I don’t draw, but I tell them I’m imagining these things. We had an art director from Portugal and from Spain, and I had two Filipino designers as well. So we work on it together: the look, the clothes, the sets, everything.

What about the ship?

We found the real Victoria! They renovated it, but it was intact. It’s amazing. They were built like rocketships, man. They’re strong. They can withstand big storms. It’s amazing. They built those ships in the early 16th century, and, man, the engineering was really amazing. Unbelievable, the way they put things together without even nails.

Did you design any elements of the rest of the boat?

Just little things. Some adornments, like the ropes and everything. But the sails on the replica, they were still there.

Was it difficult shooting on the open ocean?

Yeah, yeah, of course. Especially when we were outside. We’d be on these speed boats shooting and it’s windy and we’re always drenched, always wet. I got sick during the shoot because we were always wet and it was very cold. The wind was strong and the waves sometimes very strong. It was a hard shoot.

That’s fascinating, because the motion of the sailing footage in the film seems so tranquil—still and meditative.

Yeah, we have great stabilizers now. Even within the camera.

Would you stabilize shots in post-production as well?

A little, a little. But within the camera and with some DJIs, it’s already really good.

What camera did you shoot with?

Just one camera: the GH7. My camera. A Lumix. It’s very small. It came out early last year. I’ve been using the GH series for a while. I have a GH1, but I didn’t use it for cinema—it was a gift from a friend—but then I realized, “Oh, my God, this camera is very capable.” The GH2, the GH3, then the GH5, and now the GH7. I’ve been using the series for some time. I have a relationship with the GH camera. I know it by heart.

How much of the cinematography are you responsible for compared to Artur Tort?

The early Philippines scenes, I shot them. Then, when we got to Europe, Artur took over. And it’s good, because we have the same process: he works with one guy and I work with one guy. It’s easy for us. And I was so connected with this small camera. Albert [Serra] and Artur were using their Blackmagics, the small ones. It’s almost the same as the GH series, so it’s easy to adjust. The adjustment is more with the team. Because in Europe we had bigger teams instead of a small crew. But the technical things are easy for us. We work the same way.

There’s such a consistent look across the whole picture, between the two cameras and DPs. And one of the things that stuck out is that heightened, naturalistic glow to so much of the footage. Whether you’re looking at people wailing or staring at the aftermath of terrible violence, there’s this beautiful glow. It reminded me of the visual aesthetic of Pacifiction, which Artur also shot, of course. And I wondered how you talked about that and achieved that look.

The grading. It’s very much in post. During the shoot we shot, I would say, 70% in natural light, and then Artur worked on the color in post-production. Little adjustments, some glows here and there to make it more the color of the early 16th century, so to speak—how they looked then. Thinking about the source, the sun when you’re in the open. And Artur is very good with that—the color science.

There’s also a strong emphasis toward everything being in-focus in the frame, too.

Yeah, we did deep-focus all the time. We didn’t use shallow-focus, where only the forefront is visible. It’s very Orson Welles. Deep-focus, deep-focus. We talk about Welles and other guys who did that really strong.

What was the basis behind the decision to never move the camera unless something below it was moving?

It’s always been my language. Many of my works, it’s always static shots and very much detached—not doing a lot of concepts. I avoid that. It’s very observational, in a way. Letting things happen other than the lens imposing all the cuts, manipulating all the angles—I don’t want to do that. That’s always been my language in the cinema.

You and Artur are co-listed as editors, too. How did you split the edit?

I did the first cut. I did two or three versions of it: a long one, then abridging it, until I got it down to my original cut of three hours and twenty minutes. And then when I decided, “Okay, this is the cut,” I sent it to Artur and he worked on it a bit. That’s it. It’s simple. I did the cut and Artur refined it. It’s very collaborative.

When you’re writing the screenplay and when you’re directing, is everything you’ve written and are shooting something you expect to be in the final cut? Or is there a lot left on the cutting room floor?

We shot a lot. It can go 12-15 hours. I can actually cut three films there.

Is that also because of the way you write?

Yes, that’s always been my process—to just keep going. Writing and writing, observing things, then adding onto it again. I’m always open to what comes up. For example, if we’re shooting one day and I see a window to improve the narrative, improve the character, I go for it. I write it and send it back again to have it translated to Spanish and Portuguese and read it for the group. For me, I’m always open to that. I’m not constricted to, “This is the script, we do the storyboard and follow it.” No. There’s a lot of freedom in the writing as well. Waiting for signs, waiting for gestures. The nuances that actors give: I’m open to that. If Gael’s gestures are suggesting something, then I follow that. I love that I can follow that.

Do you have a shot list at all going into each day?

No, no. I plan it once we get to the set. There is no plan. We have the script, and if Artur’s on the camera, I say, “Artur, this is the angle,” and okay, that’s it. It’s very simple. Because I’m more into creating a relationship with the locations before shooting. It’s important. I need to inhabit the places where we shoot. I have to understand it; I have to smell it. I need to have that kind of thing before I shoot. I don’t want to do a film where I don’t know the places where we should, the ones where they just bring you there and say, “This is the set.” It’s very easy to find the frame or the look of the camera because I already have a relationship with the locations.

Does going about it that way make it harder to secure financing?

It took us around five years to be able to get all the funds. It’s low-, low-budget actually. A little from a lot of different companies. It’s not that much, but we worked on it.

What made you want to work with Gael García Bernal?

It’s always been our choice. When Albert, Joaquim Sapinho, and I talk about who’s going to play Magellan, immediately we thought of Gael García Bernal. It was a strange decision, as well, because Gael is half-caucasian and half-indigenous. He’s not pure white, and Magellan was pure white. But Gael is half-caucasian and-half Aztec-Mayan or something. He’s indigenous. And the good thing about Gael is, he’s very knowledgeable. He knows history: he can talk lengthily about South American history, Mexican history, American history. He knows Magellan and the Magellan saga. He has this deep, deep knowledge of the character and history, so it’s easy for him to inhabit not just the character but the whole setup—you know, that whole universe, the century and the years when it happened. He has a vast knowledge of it all, so it’s easy for him to commit to the character, as well.

Was it different working with a global superstar for the first time?

Of course. [Laughs]

Did that bring complications to the set, or did it offer more experience for everyone else? How did that work?

There are a lot of adjustments. I was so used to working alone when I started, and then eventually I had a little crew. I’d have five to seven people working with me: one guy working with me on the camera, two guys helping me with the design, one guy for the costumes, one supervising, that’s it, the whole thing. But with Magellan I had to deal with a big group from Portugal, a big group from Spain, a big Hollywood actor like Gael, so it was a lot of adjustments. But it was cool! It’s a good experience for me, to have that kind of setup where, okay, I have to break a lot of my processes now, like writing.

I’m so used to writing the script at night and shooting it the next day, but with this, I had to advance the script because we need to translate to Spanish and Portuguese. So I’m writing the script in advance so Gael can learn it in Spanish and Portuguese. We had translators. There were a lot of adjustments, culturally, as well. There’s a lot. And it’s good. I saw things; I’ve learned things. For me it’s very enlivening, as well, to have different methodologies and perspectives. The discourse is good, the dialogue is good.

How did you meet and come to work with that powerhouse producing team in Serra, Sapinho, Marta Alves, and Montse Triola, who did Pacifiction, Misericordia, and other recent greats?

The idea came first with Albert. He curated some of my films in Barcelona, and we were hanging out one day in Barcelona and he said, “You know, we can help you out with your films, if you have ideas that connect Spain and the Philippines.” And I was like, “It’s Magellan!” And the same with Joaquim: he loves my work and was like, “We can work on something, we can help you if you have ideas that connect Portugal and the Philippines and we can get funding from Europe.” So I said, “Magellan!” They’re also friends, so we got together and it came naturally to us.

We were talking about Magellan, so I started researching and they started looking for funds. It was very collaborative and there was a lot of philanthropy involved, helping each other out. And the Filipino commission came as well, eventually, so yeah: it’s little money. Not that big. It’s low-, low-budget. By Hollywood standards and European standards, it’s still low-, low-budget.

It doesn’t look like it, but I believe you.

Cinema can look big even with a small camera. It’s how you do it, how you use it, how you articulate things in a way.

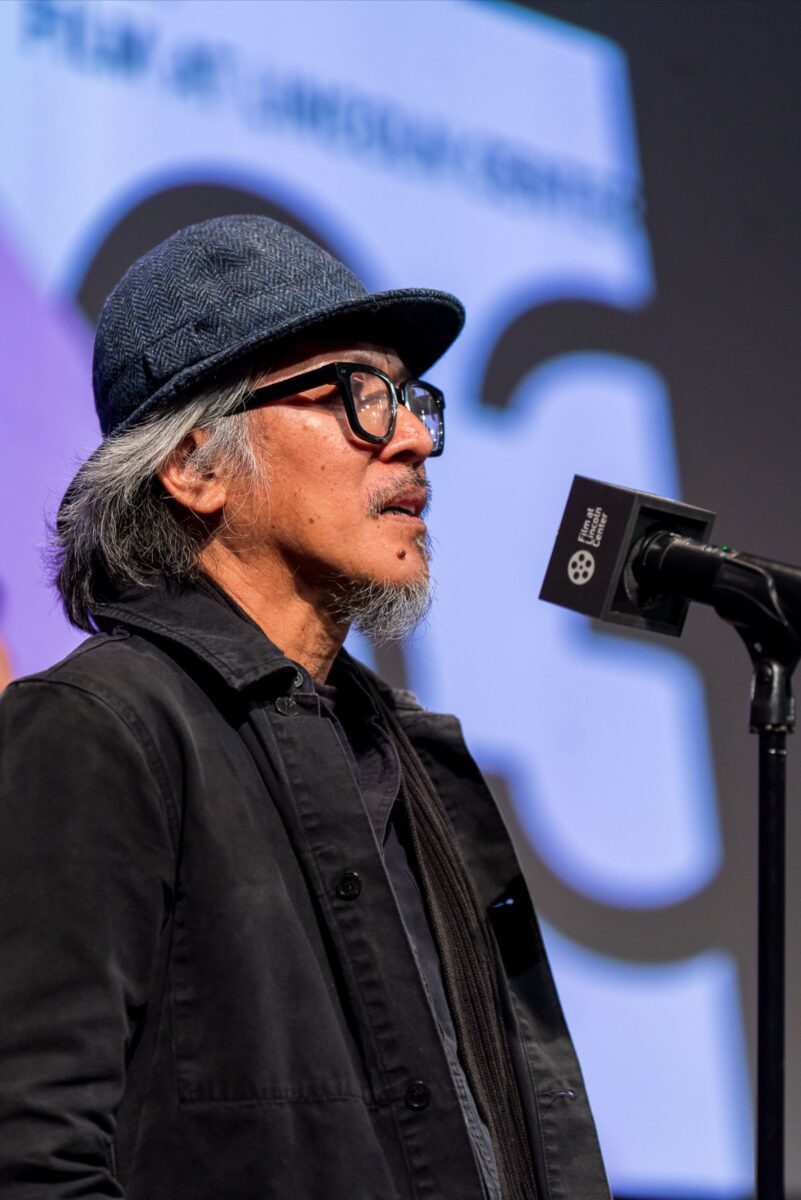

Photo by Colleen Sturtevant. Courtesy of the 63rd New York Film Festival.

On the character of Magellan, you present two distinct sides to the explorer. One, the crazed Catholic colonizer who is often filled with rage but silent about it until some outburst happens. But there’s a gentle, soft, open version of Magellan that you portray too. Can you speak to that choice?

Right from the very beginning, I didn’t want to create a Magellan that’s very heroic, like the way they do things in Hollywood. Napoleon, Alexander the Great, Ben-Hur—all these heroic figures. I wanted to look at Magellan like us, like a real human being. He was ambitious. He was, of course, in love. He had pains as well. He was a real human being. Ferdinand Magellan is like us, you know? I wanted to simplify things and understand him the way we understand our friends, our sons, our daughters, our wives. It’s the same. I want to build with him in a very reminiscent way—a person I’m talking with. And I’m writing the script like that: he’s beside me, I’m talking to him. I want to see him that way.

Did you do a lot of research into his life?

Yes, yes. A lot of reading. A lot of discoursing with historians as well. All the history in the Philippines—in Cebu, specifically. You can hear music about Magellan. One of the most popular songs in the country is about him—it’s called “Magellan.” You can see it on YouTube. “Magellan” by Yoyoy Villame. It’s like one of the national anthems of the Philippines; it’s a great song. And you read about it, you can see him everywhere. He’s part of our culture.

How were you taught about Magellan growing up, and how is he thought of in the Philippines? Is he seen as more of a villain, or is there’s a twisted celebration of him from the Catholic side?

All of those, man. We’re fixated on it. 80% of the country is Catholic and it started with him. The biggest icon in the country is still the Santo Niño, the Child Jesus, and every Catholic household has a Santo Niño, and it came from Magellan. The biggest religious festivals in the country are all about the Santo Niño. That’s Magellan! In fact, the biggest religious festival, the Ati-Atihan on Panay Island near Cebu, is about the Child Jesus and it’s mixed with our old Pagan beliefs, our old Pagan practice. It’s weird, but there’s the Santo Niño. It’s ubiquitous, man. The Santo Niño that you saw [in the movie], the first time he gifted the Santo Niño to the wife of Humabon in Cebu, it’s still with us. That Santo Niño is still with us. We never escaped.

Were you raised Catholic? Or a mix of Catholic and pagan? Or something else?

My father was a communist-socialist, but my mother was a devout Catholic. So there’s that big, complicated mix in our family. In the early days, my father was imposing a lot. We don’t celebrate birthdays, we don’t celebrate Christmas, all those things. But when he got old, my mother won. He converted to the Catholic system. So, in a way, it was a weird, weird conversion from father. Before he died, he became Catholic, but he was a social worker and socialist-Marxist all his life. But my mother was imposing as well with her Catholic beliefs. So we had these complex perspectives in our head when we were growing up.

So much of the film focuses on slain indigenous bodies, but we don’t usually witness the violence take place. Instead we see the aftermath. It comes across as a symbol and the cost of a western wealth and power. Is that something you wrote out in the screenplay–witnessing the aftermath and fashioning the frames to reflect those themes? And how did you talk about those shots as you were making the film?

Even in my early works, it’s been that way. It’s very journalistic. I don’t want to show spectacle, especially on the nature of crimes or the physicality of violence. I want to use the word “barbarism.” For me, to make that a spectacle in cinema is obscene. I just want to show the aftermath, in a way, out of respect for the human condition. I don’t like to play with violence the way it’s depicted in commercial cinema. Sometimes, even the killing they do is in slow-motion, and it’s so obscene. Why do we have to glorify violence that way?

I wanted a very journalistic way, like I’m a reporter, a big reporter—the police beat. When they say, “A man was killed,” and you go to the journal, you see the aftermath; you see the dead bodies. I wanted to do it that way. And then you go back and investigate why he died. What’s the connection to how he lived? You still have respect, even if he’s a criminal. You have to talk about psychology, not condemning him and judging him. In the cinema, I want to use the word “respect.”

Magellan opens in theaters on Friday, January 9.