Note: Hugo was screened at the New York Film Festival as a work-in-progress with color correction, sound mixing, titles, 3D and visual effects not fully complete. Check out my detailed impressions below, but look for a full review on the final film when it releases next month.

Being a film lover and director go hand in hand, but it is difficult to find a more passionate, well-educated cinema historian than Martin Scorsese. The director of classics such as Taxi Driver and Raging Bull has a seemingly endless knowledge of the medium, frequently noting the influence that filmmakers like Satyajit Ray and Italian neo-realist pieces such as The Bicycle Thieves have had on him. One can see the profound effect in his filmmaking, with such a firm control on and expertise in the medium coming through his frames. By presiding over a film preservation foundation, the auteur also hopes the profound effect cinema has on the world is not lost. So, what does this all have to do with his first foray into 3D and only family film in a career spanning half a century? Well, everything.

With Hugo, Scorsese has created a cunning ruse, with the first half being as audience-friendly as the marketing suggests, followed by a swift turn of events. A striking lesson in film history and the importance of film preservation is unraveled in the remainder – and all with a level of enjoyment that only Scorsese could bring. Part of the surprise is just how exactly this switch is made and what it means for the characters it involves, so I’ll stay as vague as possible.

Scripted by John Logan (The Aviator, The Last Samurai) and adapted from Brian Selznick‘s novel, the story is centered on Hugo Cabret, played by Asa Butterfield. The orphaned child lives within the walls of a train station, scurrying throughout the nooks and crannies and stealing food to survive, all while serving as operator of the many clocks, a job passed down by his out-of-the-picture, inebriated uncle (Ray Winstone).

One thing is made abundantly clear from the beginning: When Scorsese said with 3D “every shot is rethinking cinema,” he was not kidding. From the opening, as a flurry of snow flakes grace the screen and we glide in one motion from above the city, down into the main platform of a train station (albeit with computer-generated patrons in this work-in-progress), the effect is immediately realized. Each snow flake is perfectly layered to give the ultimate sense of depth, and even further behind, we see the worn city of Paris stretch to the horizon. This attention to detail is the savior of a format that continues to receive poor reception with shoddy post-conversions and lack of specific vision.

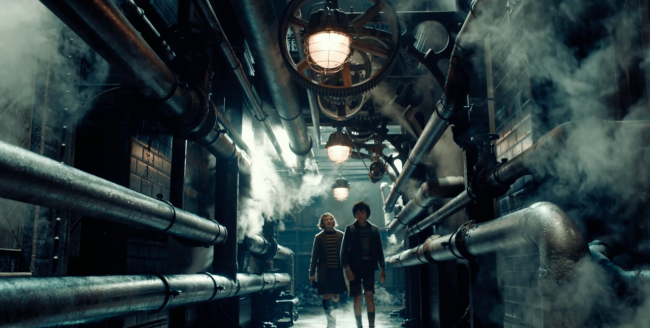

To introduce us to the world of Cabret, Scorsese takes a note from his Goodfellas handbook and, in a single shot lasting a few minutes, we follow our lead through this industrial setting. Smoke enters the frame as we track along rows of pipes, each becoming realized before our eyes in this new format. Cabret jumps down a winding slide, descending floor by floor as the camera stays behind him, putting us right into his perspective. In the main clock tower, the inner workings spring to life as he’s able to show how all these pieces fit together, a major theme expanded on later in the film.

Being mostly free of dialogue in these initial scenes, only Howard Shore‘s French-influenced score and the hustle and bustle of the station add to the marvelous visual storytelling. The live-action 3D is the best I’ve ever seen, as city landscapes are suddenly given life with trains passing in the background and lights in the distance, each containing their own specific depth of field.

Sacha Baron Cohen is the stubborn Station Inspector, who is always on the lookout for Cabret and his hijinks. He provides the most laughs here, especially with his ongoing crush on the train station florist (Emily Mortimer, who is mentally altogether now after Shutter Island). There is a key moment in the third act where our lead is the main focus, but Scorsese takes an unnecessary detour to tie up the other people we’ve come to know at the train station in an attempt to get the audience caught up for the resolution. It could work with tighter editing, but it only serves to distract in this cut.

For much of the first half, as Cabret looks to uncover his special notebook from a local shopkeeper (Ben Kingsley) and he encounters a friend in Isabelle (Chloë Grace Moretz), there is a question of what exactly Scorsese is attempting to accomplish. The repetitive, sometimes tedious nature of these scenes don’t click until the big picture is revealed. Once it occurs, it becomes clear that Scorsese was experimenting with the 3D just like Georges Méliès, a key figure in this film, was an early special effects pioneer.

Scorsese makes sure to recognize all the early cinematic icons that came before. After providing a parallel with the clock adventures in Safety Last!, one montage displays both what’s widely considered to be the first film ever (Exiting the Factory) and the first “controversial” film (William Heise‘s The Kiss), among many others. He shows us how the audience feared a gunshot straight at them in Edwin S. Porter‘s The Great Train Robbery and an oncoming train in The Lumière Brothers‘ Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat. Just as those films astonished early theatergoers, it is easy to be stunned by the way Scorsese incorporates technology here. The inclusion of Train Robbery serves as a connection to Scorsese’s own career; if you’ll recall, one of the final shots in Goodfellas homages Porter’s work when Joe Pesci shoots at the camera.

Hugo is a film that everyone should see, but not because it appeals to a mass audience. Scorsese has crafted a work that educates as much as it entertains, and one that I appreciate more than inherently love. It has the power to be that one experience to turn a casual young moviegoer into a lifelong film fanatic. After all, a young Martin Scorsese was probably no different than Hugo Cabret himself.

Hugo hits theaters nationwide on November 23rd, 2011.