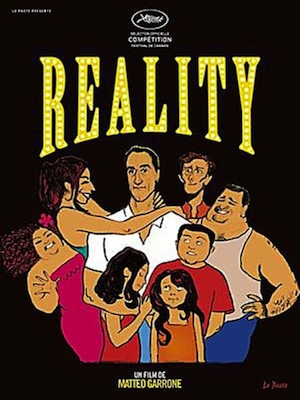

Matteo Garrone‘s Reality never becomes the vicious criticism of unearned fame and non-stop television one might expect from the man who revived the mafia picture with Gomorrah only four years ago. That film had a raw energy that jumped off the screen. Garrone’s follow-up is decidedly more concentrated and deftly-paced, the filmmaker determined to explore the world of his anti-hero Luciano (the engrossing Aniello Arena), a family man living simply and happily in Naples who allows himself to fall apart in pursuit of his dream to be famous.

What begins as a funny party trick at a family wedding escalates into obsession. We watch Luciano put on a dress and some make-up to have some fun with Enzo, a star from reality television paid to make an appearance at the reception. This well-received prank, along with the constant compliments his extended family throws his way, convince the man he should try out for the next season of Italy’s “Big Brother.”

What follows is a dissent into obsession that begins funny before it becomes both something tragic and tragically familiar. Garrone is careful with the tone here, beautifully toeing the line between comedy and drama. We laugh at Luciano but never feel he’s being bullied by the film he is in.

Arena is hypnotic to watch, his face enough to carry some scenes all the way through. The simple, punctuated score from Alexandre Desplat only adds to these moments. Here at the festival, Desplat has three of his scores accenting three separate films in competition, his apparent penchant to keep impossibly busy not once hurting the scope and style of his music.Where Gomorrah basks in its docu-style of framing, Reality takes its time with each composed shot, moving fluidly about the corner of town Luciano and his family live in. This is the same Italy Gomorrah exists in, where the pain and brutality hurts the same, only it takes longer to get there.

Arena is hypnotic to watch, his face enough to carry some scenes all the way through. The simple, punctuated score from Alexandre Desplat only adds to these moments. Here at the festival, Desplat has three of his scores accenting three separate films in competition, his apparent penchant to keep impossibly busy not once hurting the scope and style of his music.Where Gomorrah basks in its docu-style of framing, Reality takes its time with each composed shot, moving fluidly about the corner of town Luciano and his family live in. This is the same Italy Gomorrah exists in, where the pain and brutality hurts the same, only it takes longer to get there.

Both the film’s opening and closing shot traverse from the sky to the earth and vice versa, accenting Luciano’s building, “head in the clouds” perception of life. It’s when we, and Luciano, are brought to the church for salvation that the depths of Garrone’s observations begin to take shape, transforming his film from woeful to heartbreaking. Religion cannot help this poor man any more than Enzo the star, who’s trademark catch phrase is simply “never give up” and “keep believing.” To simply tell those you love to keep trying at an impossible, foolish dream is as irresponsible as the dream itself. This foolishness comes to a head in a scene that features perhaps the best performance by a cricket since Pinocchio. Perhaps the film should have come to close soon after this moment, as the third act drags on a bit longer than necessary, the razor-tight pacing Garrone achieves throughout the first half getting a bit lost.

Though the surrealism of the ending fights against the grounded narrative that comes before it, it feels like the right note to end on. Faith emerges as the culprit here, a weapon as dangerous as any gun when stricken with blindness.