A shot late in Andrey Zvyagintsev’s Loveless encapsulates both the film’s overarching message and its author’s bludgeoning directorial approach. One of the protagonists, Zhenya (Maryana Spivak), gets on a treadmill and gradually increases its speed, quickening her steps until she reaches a steady running pace. Just in case we had yet to clock that the characters are supposed to be representative of Russian society – be it from the transparently schematic script, or the fact that one of the film’s opening images is a lengthy static shot offering little to look at other than a Russian flag hanging off the side of a building – Zhenya wears a tracksuit emblazoned with the country’s national colors and “RUSSIA” printed in giant letters across her chest. Zvyangintev frames her from the front, holding the shot for several seconds. Then, once he’s made sure everyone’s had sufficient time to decipher his complex visual metaphor about a country running forward but getting nowhere, he initiates a slow track towards Zhenya until she’s framed in a tight facial close-up, her dejected stare directed straight at the camera. I’m not 100% sure here, but I assume we’re supposed to feel implicated.

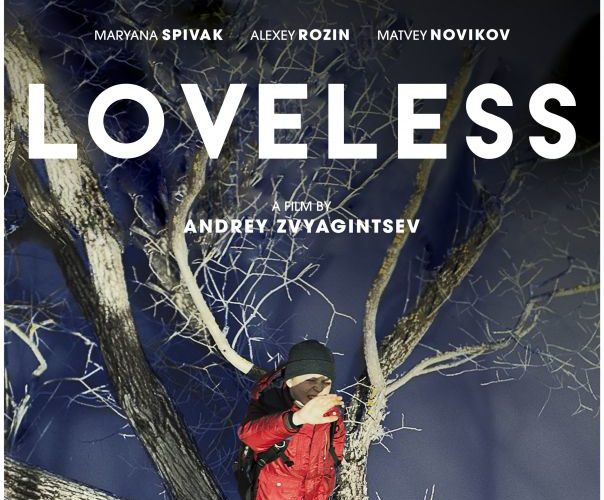

Although Leviathan, Zvyagintsev’s previous and far-superior effort, was hardly a masterclass in nuance, a palpable sense of empathy and flashes of humor largely compensated for its lack of subtlety. These are sorely lacking in Loveless. The film’s title may refer to the protagonists’ marriage and its symbolic connotations, but it’s also a perfect description of Zvyagintsev’s treatment of his subject matter. Characters seldom comes as despicable as Zhenya and her husband, Boris (Alexey Rozin). They’re introduced at film’s start, during which they’re already mid-divorce, engaging in a vicious screaming match, each trying to outdo the other in proving who’s more resentful of their twelve-year-old son Alyosha’s (Matvey Novikov) existence while the child hides in the next room, listening to it all and crying his eyes out. Not long after, Alyosha disappears – this goes unnoticed for almost two days; both Zhenya and Boris were busy hanging out with their respective lovers – and, after recruiting the help of a private agency, the parents start a long search for the boy.

Loveless improves significantly once the search mission gets underway, and, thankfully, this makes up the bulk of the film’s running time. By meticulously following every step taken in such an occurrence, Zvyagintsev slowly and expertly builds up tension and foreboding regarding Alyosha’s fate. And, as the chances of finding him dwindle, his odious parents are gradually beaten into contrition, growing more recognizably human – and a lot more bearable. The widescreen lensing by Zvyagintsev’s regular cinematographer Mikhail Krichman is consistently stunning, and the tableaux he crafts from sights such as a group of red-vested men combing an autumnal forest or systematically searching through derelict buildings are nothing short of breathtaking.

In the press notes to Loveless, Zvyagintsev shares that Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage was one of his main influences in making this film. Considering that the mysterious disappearance of a central character initiates a slow-burn existential crisis for the middle-class protagonists, it’s safe to assume Antonioni’s L’Avventura was also a point of reference. However, when an epilogue shows this crisis to have had no consequences whatsoever (remember the treadmill?), the ordeal of the search comes to represent but a lengthy and borderline sadistic come-uppance. The bitter taste left by this realization has no parallel in the work of Bergman or Antonioni, neither of whom peddled such haughty, facile, and ultimately futile didacticism.

Loveless premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and will be released in the U.S. by Sony Pictures Classics on February 16. See our coverage below.