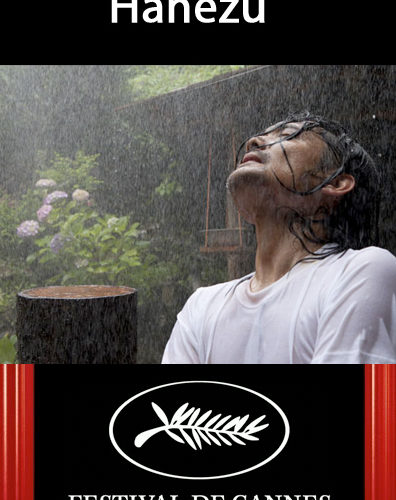

Filmmaker Naomi Kawase has been a soft spoken staple at the Cannes film festival ever since being the youngest recipient to win the Camera d’Or for her debut feature film Suzaku. Known for a subdued lyrical style peppered with symbolism and metaphors, Kawase’s latest film Hanezu continues this tradition to varying degrees of success. The title’s meaning represents a certain shade of red, used in ancient Japan poetry that is meant to evoke imagery of blood, the sun and fire. In Kawase’s film, the enigmatic director attempts to represent the Asukua region of Japan, an ancient birthplace of much of the countries deep rooted sense of culture, through an allegorical tale of two lovers whose quietness becomes their undoing. Despite being beautifully shot by the director herself, Hanezu has a pervasive feeling of simplicity in hopes of the audience finding deeper meaning for what the film is supposed to represent.

The film opens with a hypnotic shot of a conveyor belt carrying rocks from the Earth to a pile below. This is followed by perhaps one of the singular most beautiful shots of the moon ever committed to film, as it towers over the land like a giant deity. From these dual moments of beauty and destruction, the film plunges into a modern day love story of two extremely soft spoken people, Takumi (Tôta Komizu) and Kayoko (Hako Ohshima). While there is an obvious romantic connection between the two, their relationship is always subdued and the focus shifts more often than not on the elderly people surrounding the couple, who continually reminisce about this land’s ancient traditions and how it has drastically changed. One day in passing, Kayoko mentions to Takumi that she is pregnant before nonchalantly biking away into the village. Unsure of how to handle the news, Takumi decides that it finally time for him to mature and find a living that could support a child.

Kawase has a style familiar to Mike Leigh in the fact that she doesn’t rely heavily on a script and instead prepares the actors to transform into the lives of these characters and then act out what they feel would be natural. There is a direct emphasis on creating an environment for these characters which allows them to inhabit their lives, while the filmmaker watches their lives unfold before her own. The problem lies with many scenes in the film feeling aimless and thus their is a continual feeling of detachment from any kind of connection one might have to their lives. This might be different if you are Japanese and are familiar with the history of the Asuka region, though even then, you would have to rely heavily on personal interpretation.

As the film progresses there are moments where Kawase clearly aims to shock, despite the dramatic turns sometimes feeling awkwardly forced. They feel like they are at odds with the flow of the film which aims to be naturalistic and restrained. Towards the end there is one moment that is intended to be the climax of the film but feels undeserved and merely there purely to shock. This is followed by a title card at the end of the credits which tries to explain the metaphorical nature of the film really being about the ancient land and the countless soldiers who had died here prior to the romantic fable. It almost feels like Kawase is forcing her cinematic motivations down the throats of the audience causing immediate dissonance. It’s unfortunate that much of Hanezu feels similarly disconnected because at it’s core is a beautiful lyrical tone piece on one of Japan’s most sacred ground.