Kicking off this week at NYC’s Film at Lincoln Center and The Museum of Modern Art, the 51st edition of New Directors/New Films brings together highlights from Sundance, Berlinale, Venice, Locarno, Rotterdam, and many more to provide an essential snapshot of new filmmaking talent. With Audrey Diwan’s Golden Lion winner Happening commencing the annual festival starting Wednesday, it’s one of 12 films we can recommend as we also look forward to catching up with the rest. Check out our picks below.

The African Desperate (Martine Syms)

It’s a hot July day in upstate New York when Palace (Diamond Stingily) sits for her final art school exam, a passive-aggressive interview with an all-white faculty that leaves her with that soul-crushing question: what are you going to do next? The answer, in Martine Syms’ rollicking debut feature, is a night-long graduation party, a bacchanal that sends Syms’ friend and fellow visual artist Stingily down a drug-fueled, Divine Comedy-like journey into her academic bubble with a few of its eccentrics dwellers—nearly all of them white. Graced with colors lush and garish—juxtaposing the woods’ greens with the party’s neons—and peppered with all kinds of GIFs, memes, bold fonts, and reaction videos, The African Desperate is a boisterous satire of Palace’s bohemian world and a Portrait of the Artist as a Young Black Woman building her voice over and against it. Stingily—with her deadpan humor, fluorescent orange mane, and no-nonsense swagger—makes this odyssey a riveting and ultimately cathartic watch. – Leonardo G.

The Cathedral (Ricky D’Ambrose)

What makes the fabric of our upbringing? The memories we’ll reflect on after those years have passed are often not what we may hold onto in a moment filtered and refracted through a thousand more experiences. Following his hour-long debut feature Notes on an Appearance, Ricky D’Ambrose’s Bressonian style continues with The Cathedral, a less intellectually rigorous outing that still impresses with its sense of personal significance, recreating slivers of a life experience over some two decades to form a vivid recollection of both the fracturing of a family and the United States at large. It’s an ambitious undertaking for an 87-minute film, and while this lofty aim can result in a few passages striking a bit broad, one comes away admiring D’Ambrose’s meticulously committed approach to storytelling. – Jordan R. (full review)

The City and the City (Christos Passalis and Syllas Tzoumerkas)

Directors Christos Passalis and Syllas Tzoumerkas describe their film The City and the City as the untold story of Thessaloniki, Greece. It isn’t that because there’s a lack of interest, though. Rather this story is one the majority-Christian city doesn’t want told. Why? Because it damages their narrative. This is their home and that’s all anyone needs to know. To believe the start and end of a place’s history lies with those currently in power not only exposes you as a member of that power, but also one keenly aware of what that “untold” story says. The only reason you could want to suppress an undeniable truth is because you know that which is yours was built upon the bodies of those you supplanted. – Jared M. (full review)

Dos Estaciones (Juan Pablo González)

Contemporary Mexican art cinema, if not exactly miserabilist, has definitely aimed to disturb and rattle, the subject matter of narco-trafficking and the cartels never far away. Juan Pablo González’s first fiction feature, much-admired at Sundance this year, brings a fresh eye to portrayals of the country, focusing on the professional affairs of a Jalisco-based tequila factory baron who finds a potential romantic connection with her new secretary amidst environmental threats to her crop fields and American multinational firms with eyes on her business territory. Dos Estaciones––translatable as “two seasons”––is a vivid snapshot of a locale in transition, and also opening up, with its elements of queer and trans romance. – David K.

Fire of Love (Sara Dosa)

In a bond forged over mutual fascination (or obsession) with the mysteries of volcanoes, Katia and Maurice Krafft dedicated their lives to discovering everything they could about these natural phenomena. Forces of both awe-inspiring wonder and tragic disaster, Sara Dosa’s archival documentary Fire of Love gracefully captures this extreme dichotomy while also getting to the heart of what drove this couple to abandon a routine, domesticated lifestyle and literally sacrifice their lives in the mission to save others. In telling their devotion to one of the natural world’s most dangerous forces, Dosa crafts a documentary that would make Herzog proud—and an ideal double feature with Into the Inferno, his collaboration with volcanologist Clive Oppenheimer, which also features the Kraffts. – Jordan R. (full review)

Happening (Audrey Diwan)

The year is 1963. The location is Angoulême, France. The woman is Anne (Anamaria Vartolomei), a bright student faced with the weight of the world when she discovers she has an unwanted pregnancy. Facing the country’s strict anti-abortion laws, Anne’s predicament puts not only herself in danger, but also any doctor who’d be willing to help her achieve the procedure for which she’s desperate. So begins Happening, Audrey Diwan’s Golden Lion-winning adaptation of Annie Ernaux’s semi-autobiographical 2000 novel of the same name (L’événement). – Mitchell B. (full review)

The Innocents (Eskil Vogt)

The Innocents, the assured sophomore feature from Eskil Vogt, is a prickly film about childhood morality designed to get under its audience’s skin. It quickly becomes apparent that the remaining unease has very little to do with the lingering effects of slow-burning horror, and much more with problematic casting choices that render the drama uncomfortable. It’s a shame as this is a confident effort, utilizing many of the same vague supernatural aspects as 2017’s Thelma (for which Vogt co-wrote the screenplay with frequent collaborator Joachim Trier) to tell a completely different coming-of-age story. It makes for an unsettling, more overtly horrifying companion piece, but one with too many noticeable flaws to properly escape from its shadow. – Alistair R. (full review)

Nanny (Nikyatu Jusu)

With Nanny, Nikyatu Jusu presents a more haunting depiction of the American Dream. Her feature debut nods to Ousmane Sembène’s seminal Black Girl while distilling the trials her parents, immigrants from Sierra Leone, endured as Jusu grew up in Atlanta—a mix of domestic drama and frightening images to make us fellow outsiders in a suffocatingly insular world. – Margaret R. (full review)

Onoda – 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (Arthur Harari)

Arthur Harari’s stirring war film––a cause célèbre in France, mysteriously overlooked by critics elsewhere––will finally make its New York bow at ND/NF. Based on scarcely believable real events in the Pacific Theater of World War II, Harari makes a fascinating anti-war hero out of Hiroo Onoda, a Japanese holdout on the occupied Philippine island of Lubang who refused to surrender once the war ended. Running almost three hours, Harari––a rising star in France and co-writer of Justine Triet’s work––has confidently fashioned a traditional war epic in the Hollywood (or even British cinema) mode, but with an uncanny streak of absurdism running through it. – David K.

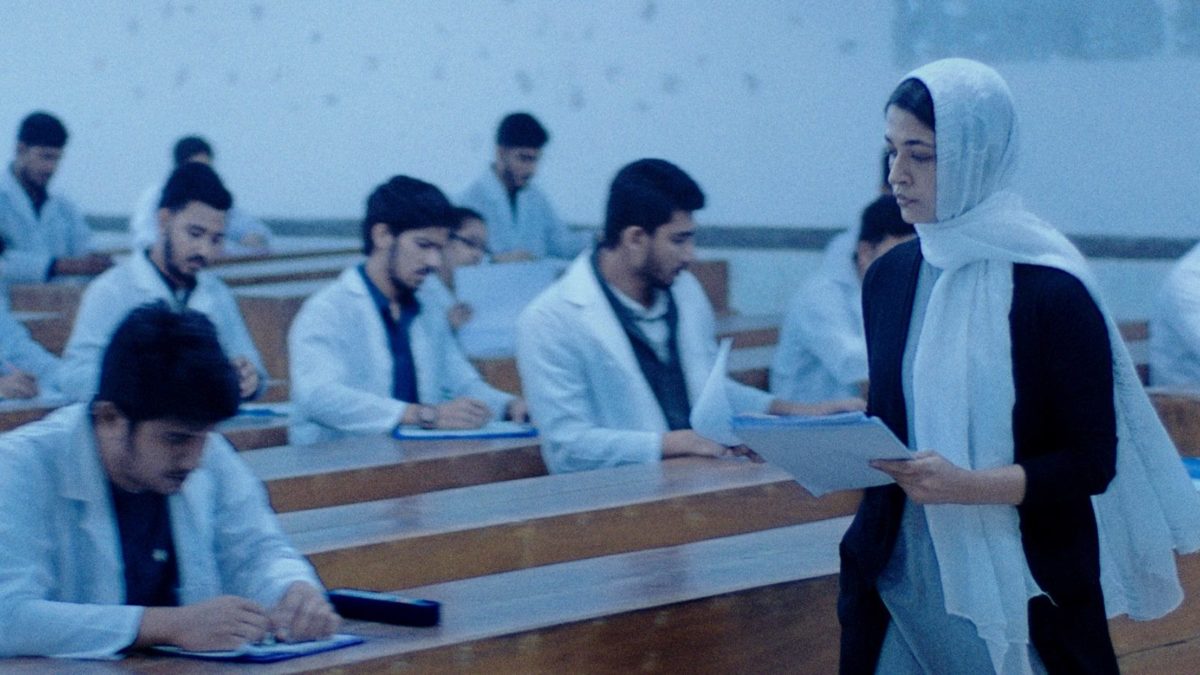

Rehana (Abdullah Mohammad Saad)

Is Rehana Maryam Noor a righteous, selfless woman or a stubborn egoist? By the end of Abdullah Mohammad Saad’s Rehana such a question is likely to pop in the viewers’ minds—her actions are fodder for polarizing opinions. Unwilling to be cowed by the monolithic systems of the medical college where she teaches and of her daughter’s school, Rehana puts up a brave fight against injustice and oppression. But are the victims of patriarchy for whom she is taking a stand ready to support her, or will she end up a lone crusader? The first Bangladeshi film to be featured in the Un Certain Regard section at Cannes, Rehana is a restrained and empathetic part drama, part thriller. – Arun A.K

Riotsville, USA (Sierra Pettengill)

Riotsville isn’t just a place. It’s an idea; a fiction written by the enforcers of order to “demonstrate the presence of a superior force.” Riotsville is portable and meant to be transplanted no matter the material conditions of what it may disturb. Riotsville is violence done to civilians in the name of maintaining their own civilized society. To put it bluntly: Riotsville is federally funded facism, and as director Sierra Pettengill’s urgent, meticulously collaged documentary outlines, it laid the foundation for the tactics and overwhelming funding of police brutality we see today. – Shayna W. (full review)

Robe of Gems (Natalia López)

I made the mistake of worrying about plot while watching Natalia López’s feature directorial debut Robe of Gems. The synopsis dares you to worry with its talk of three women colliding courtesy of a missing person in Mexican cartel territory, asking us to wonder how things will resolve. Except we already know. The bodies found in landfills and marshes throughout the film prove it. If those who are kidnapped aren’t already found dead, you can assume they will be soon. That doesn’t mean María (Antonia Olivares) won’t continue to hope for her sister’s return, though. Nor does it stop her recently-returned-to-the-countryside boss Isabel (Nailea Norvind) from joining the cause. Add Roberta’s police chief (Aida Roa) to the mix and know the woman’s memory isn’t forgotten. – Jared M. (full review)

New Directors/New Films 2022 takes place at Film at Lincoln Center and The Museum of the Modern Art from April 20-May 1. See the schedule and get tickets here.