My teenage years may be decades removed from me at this point, but that didn’t stop me from reconnecting with my brooding, uncertain inner teen when reading John Green’s effective dying kids sop, The Fault in Our Stars. Green took the familiar and maudlin and transformed them into something knowing, poignant and practically sensitive. Sure, the book’s a touch overrated, but it earned its fans with a storyteller’s affection and avoided the flabby, toothless pitfalls of similar entries in the sub-genre.

There was a touching insight into the internal workings of Green’s protagonist, Hazel Grace, who was constantly living in the valley of the shadow and trying to cull what joy she could. On film, many of the nuances of Geen’s prose were sure to be lost, leaving behind a melodramatic, Kleenex gobbling affair featuring good-looking teens dying in highly dramatic fashion. That reduction was inevitable, especially when mainstream cash is involved, but fans of the book can rest at ease. The Fault in Our Stars is a sincere and recognizable version of Green’s world and characters.

Writers Scott Neustadter and Michael H. Weber, who were similarly effective in adapting Tim Tharp’s The Spectacular Now, have hewn close to the dialogue and narrative, while extracting and streamlining the book’s competing themes of guilt, perseverance and unexpected love for the big screen. It helps of course that Now’s star Shailene Woodley, fresh off Divergent and with her co-star from that film in tow, plays Hazel Grace and gives the character a trembling, bruised agency that lends some real gravitas to the melodrama. Move over Love Story and Walk to Remember, there’s a new mildly morbid cry in town.

At the outset of the film Hazel informs the audience that “this is the truth,” an assurance that there will be no fairy tale whitewashing here, but that is a promise a film like this can’t really make. Of course, there’s a sense of manufacturing in Fault (there was in the book too), but the familiar trajectory is grounded in a painful, fragile world that makes the reality of disease and biological frailty a force the characters and their loved ones must contend with. There’s no big Hollywood movie illness here, and that adds sincerity to the cautious love developing between the two leads.

When Hazel’s withdrawn but self-possessed survivor meets the externally confident and dreamy Augustus Waters (Ansel Elgort) at a support group, they bond, not over their circumstances—both are facing cancers that went into remission after taking a major toll on their bodies—but their own realistic candidness regarding the future. The future, in fact, may as well be the closest thing a film like this has to an antagonist, sitting at the edge of Hazel and Augustus’ life, both beckoning and halting their waning hope. For teens nervous about what their own lives may hold, and how far that road in front of them extends, Fault may be cathartic, as it gives them witty and intelligent characters who move fearlessly forward in the face of a potentially crushing void.

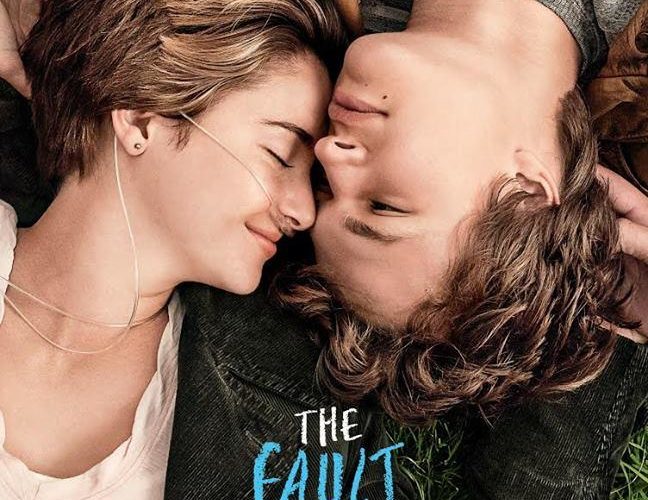

Although the direction by Josh Boone feels a bit pedestrian and occasionally flat, it’s clear early on that the film’s visual element is mostly concerned with getting Woodley’s Grace, whose terminal cancer status is constantly reminded by the oxygen tube trailing behind her, and Elgort’s Augustus into intimate, softly shot close-ups that can devastate. That single-mindedness of spirit does reduce the ambitions of the story, but it also keeps the film spare and focused. Boone never sends his actors or his film out on missions to replicate some element of the book that’s out of their reach, and when looking for a rock to cling to, he wisely retreats to Green’s words and dialogue. As such, there are certain portions that are soft pedaled to the screen, including the book-within-a-book subtext, although that novel’s author, Peter Van Houten, does appear here as Willem Dafoe, suitably morose and scintillating simultaneously.

Laura Dern also shines in a supporting role as Frannie, Hazel’s mother, but the show belongs to Woodley and Elgort. Woodley’s own pensive approach to her roles is a refreshing commodity because it allows us to watch her unpack her characters’ resilience and weakness a little bit at a time, keeping things fresh and giving us new reasons to care for them. Less assured is Elgort, who’s not quite the same cut of actor as Miles Teller in Now, although he gives the role his all and commands enough charming energy that he mostly holds his own with Woodley. It isn’t helpful that Augustus is often routed to role of dreamboat and that diminishes his own stakes in the story. All of that will likely cease to matter for those who embrace the film and its nakedly emotional core. By the final third, our theater was a mass of blubbering incoherence, and I suspect no one out there would have wanted it differently.

I have a tendency to resist this kind of material when it shows up, often because it trades up honesty and dramatic integrity for cheap manipulative tricks. The Fault in Our Stars is a fine adaptation of its source material, but its real value is that in its chosen field, it’s more honest than most and, with Woodley pushing it forward, always fascinating to watch.

The Fault in Our Stars in now playing in wide release.