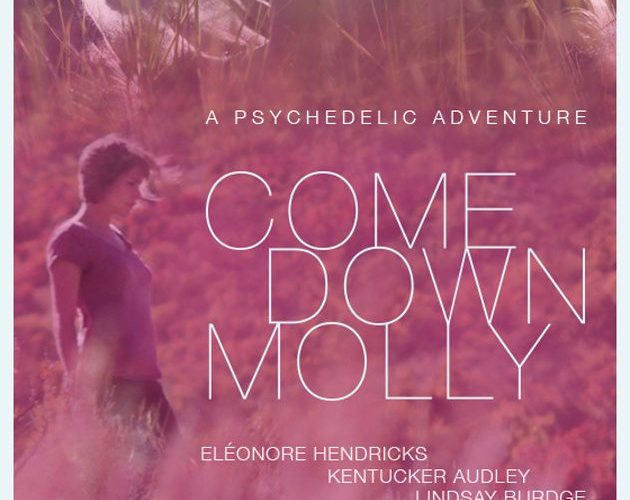

While Molly (Eleonore Hendricks) was never quite the manic pixie dream girl trope, she was certainly held in high regard by the men of her past. Recalling her wild days as “one of the boys,” she’s seemingly disconnected, finding herself adapting to the challenges of motherhood, she’s is having a rough time. Living through a kind of undiagnosed postpartum depression, she is virtually untouched by her husband Patrick (Kentucker Audley) who objects to her upcoming weekend plans. Rushing through some of the story’s more interesting material upfront, the crumbling of a young marriage that had the potential to push Blue Valentine’s concept a bit further, writer/director Gregory Kohn instead takes us where many a 20/30-something-led indie has gone before: a cabin in the woods for a reunion.

Abandoning her family against the objections of Patrick and sister/part-time nanny Amy (Lindsay Burdge) she sets off to reunite with old high school pals – an all-male crew (played by Jason Shelton, John Anderson, Jason Selvig, Sam Sundos, Benjamin Roberts and David Jette). We learn Molly was once one of the guys — she accepted them and all of their faults, and they accepted her, even if they each wanted to hook up with her. Apparently they missed a narrow window of opportunity; in one of the story’s franker passages, before the introduction of psychedelic drugs, Molly recounts a rough patch in her life.

While Hendricks has molded Molly into a fully three-dimensional character, each of the guys all seem to share the same story. Their development is one of the challenges of Kohn’s script the film does not overcome. While it would ring false to provide each of the guys a lengthy backstory with a “remember that time…” kind of trope, the lack of interesting character development grows frustrating.

An observational drama, the film’s emotional frankness comes into play when the psychedelic drugs do. Kohn handles the material with restraint and maturity as Molly’s trip becomes a minor personal journey. Wandering through the landscape, she has one memorable, tender encounter that the film handles well.

While Come Down Molly contains a good deal of emotional honesty within its brief running time, the picture seems to overstay its welcome. As a short film, free from the additional restraints of a feature, the sparse, lucid nature might have worked. The cinema of restraint, pioneered recently by Kelly Reichardt (in fact, the film may warrant some comparisons to her brilliant and beautiful Old Joy) has become the norm, stripping indie cinema of certain vibrancy while sanding down the rough edges. Come Down Molly does not appear to have been hatched in a development lab, the discipline that has infected independent films of a certain budget and ambition hinders what might have been a more interesting project had it taken a few more risks along the way.

Come Down Molly premiered at the 2015 Tribeca Film Festival.