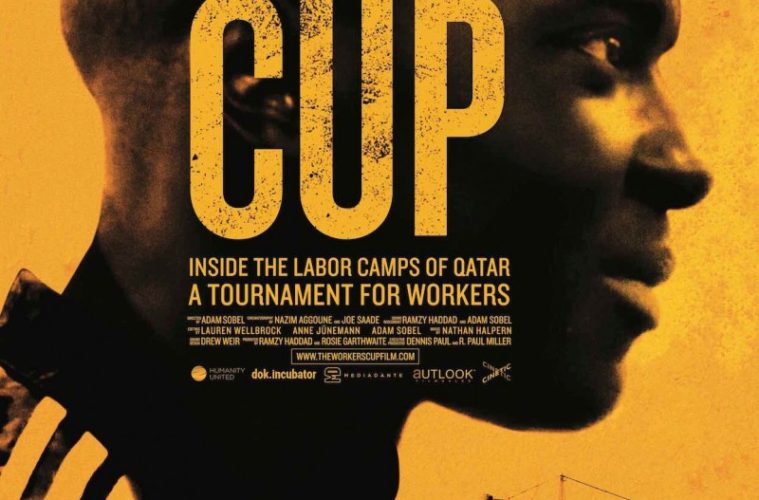

Highlighting the economies of migrant workers from Nepal, India, Ghana, and Kenya living and working in Qatar as the country prepares for the 2022 FIFA World Cup, Adam Sobel’s The Workers Cup highlights the ambitions and dreams of men caught in a form of contract slavery. Working twelve-hour days, seven days a week, a select group of men from the Umm Salal labor camp — a prison-like arrangement of temporary housing–– are chosen to play in The Workers Cup, a tournament sponsored by the same committee organizing the 2022 World Cup.

The men, who are often out of sight and out of mind, are given a voice by American filmmaker Sobel. Quite miraculously, he is permitted to have intimate access to the workers, creating an striking portrait of one team, playing for construction firm GCC (Gulf Contracting Company). The tournament proves to be rather heartbreaking, especially for Kenneth, a 21-year-old Ghanan with dreams of playing professional football. He was recruited by an agent and soon realized he was duped. His hope — that he will be seen by a scout while playing in the Workers Cup — are crushed by his immigration and contract status as he won’t be eligible for another five years.

The film focuses in large part on the team and conditions of work, specifically in a stunning series of images highlighting the around-the-clock nature of the work, evoking the scale of the late great Michael Glawogger’s studies of the world’s most dangerous jobs. The danger is real for these men that are isolated and under contract for five years. Paul is a chef working in the camp’s kitchen. Kept on site for seven days a week, he turns to social media for a girlfriend. The problem is he’s met a girl he’s attracted to, but must ask his boss for permission to leave the camp and take her out on a date. Working twelve hours a day all week leaves little time for a social life.

These men from around the globe are all caught in a geopolitical mess, some working in Qatar to support their families, other because meaningful work doesn’t exist. The team is coached by a Sebastian, a frank middle manager running nine labor camps across Qatar, who explains the trade-offs and the benefits to the Workers Cup recreation program. As a community outreach effort for sponsors and corporate investors, it costs the company $30,000 in lost wages and productivity, he estimates. For these men, it’s not just a fantasy football league — it’s their lives, and Sebastian believes he can relate to their pain as they return to work after the games wrap. I’m not sure he quite gets it.

The Workers Cup is a bittersweet portrait of the labor that built the glimmering towers, stadiums, and luxury malls: spaces these men are not permitted to be seen in public areas of. Adam Sobel would be wise to revisit these subjects in five years once they have completed the venues that comprise economic development from a World Cup that was awarded in global controversy.

The Workers Cup premiered at Sundance Film Festival and opens on June 8, 2018.