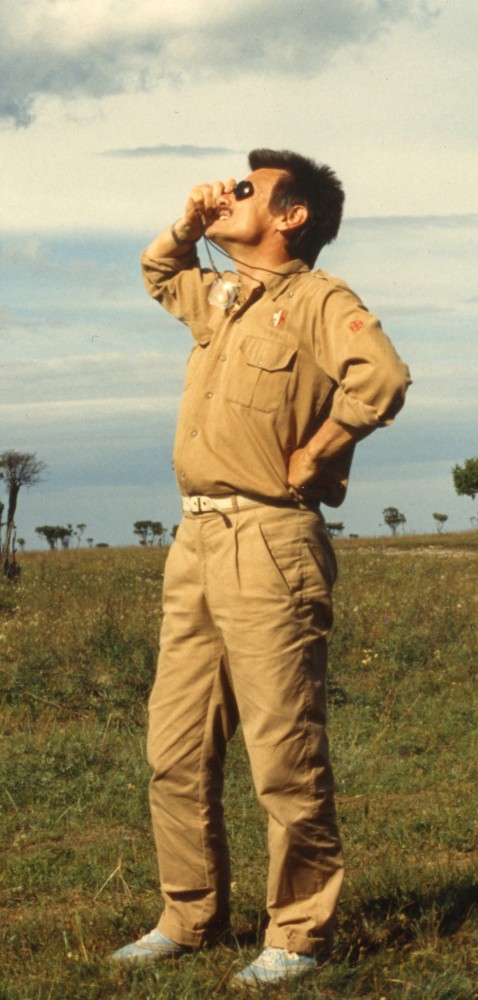

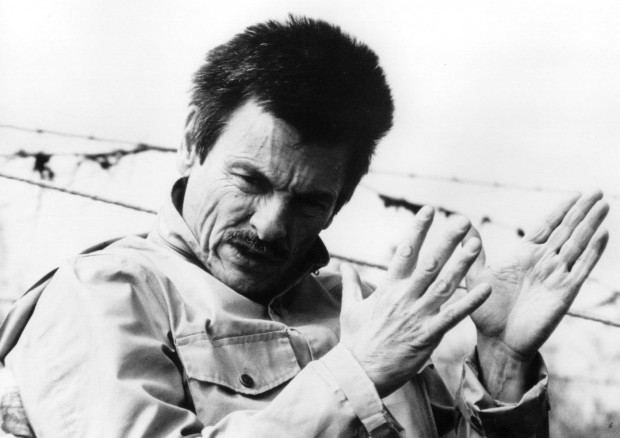

On what would be his 80th birthday, we take a look back at Andrei Tarkovsky and his profound mark on cinema.

“The director’s task is to recreate life, its movement, its contradictions, its dynamic and conflicts. It is his duty to reveal every iota of the truth he has seen, even if not everyone finds that truth acceptable. Of course an artist can lose his way, but even his mistakes are interesting provided they are sincere. For they represent the reality of his inner life, of the peregrinations and struggle into which the external world has thrown him.” ― Andrei Tarkovsky

As a young man, filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky visited a gypsy to have his fortune told, specifically, about his cinematic future. She bluntly told him he would only live to make seven films, but that each one would be an important and cherished work. The details surrounding this urban legend remain a mystery but one thing is true, the prophecy came to fruition. Arguably the most famous and influential Russian filmmaker of all time, Andrei Arsenyevich Tarkovsky is best known for his metaphysical, soul-searching themes. Poetically conveyed through long takes, his distinctive style continues to be emulated by auteurs of modern day while his body of work is still great fodder for philosophical discussion.

As a young man, filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky visited a gypsy to have his fortune told, specifically, about his cinematic future. She bluntly told him he would only live to make seven films, but that each one would be an important and cherished work. The details surrounding this urban legend remain a mystery but one thing is true, the prophecy came to fruition. Arguably the most famous and influential Russian filmmaker of all time, Andrei Arsenyevich Tarkovsky is best known for his metaphysical, soul-searching themes. Poetically conveyed through long takes, his distinctive style continues to be emulated by auteurs of modern day while his body of work is still great fodder for philosophical discussion.

Born the son of prominent Russian poet Arseny Alexandrovich Tarkovsky, Andrei was surrounded by artistic influences from a very young age. His father would soon leave the family to join the war, in addition to being evacuated from Moscow to Yuryevets with his sister and mother. Themes from Tarkovsky’s childhood and memory play a pivotal role in the reflective nature of his cinematic style. In 1954, the aspiring filmmaker began to attend the State Institute of Cinematography as part of the film directing program. It was during these formative years that Andrei’s artistic passion for film was refined as he consumed and studied films from all over the world, including French New Wave and Italian neorealists, in addition to his favorite filmmakers Akira Kurosawa, Luis Buñuel, Ingmar Bergman and Robert Bresson. His first short film was a collaborative effort with fellow film students called The Killers, an adaptation of the Ernest Hemingway novel (it’s available on The Killers Criterion Collection).

While The Killers does bear the hallmarks of the style and themes that Tarkovsky would later master, it’s an interesting pre-cursor to a short film that would kickstart his career, The Steamroller and the Violin. Made in 1960 at the Mosfilm studio, the 45-minute short is a bitter sweet tale of a young boy who, after attending a private music lesson, befriends a common everyday working man, who didn’t expect to find a friend in someone so small. In a riveting montage of a wrecking ball demolishing old buildings, themes of a new emerging Russia and shifting political tensions are subtly conveyed through mood and atmosphere. The final shot is breathtaking and a true testament to the wondrous ability of Tarkovsky to uniquely capture a moment’s subtle beauty.

Following the success of Steamroller, which earned Tarkovsky the highest possible honor from his film class, came his first feature film, Ivan’s Childhood. Based on a short story by Vladimir Bogomolov, the plot centers on a young orphan trudging through the horrors of World War II without glorifying the experience, typical to other films of the time. The opening shot, a dream sequence of young Ivan (played tirelessly by Nikolai Burlyayev) flying through the air to the top of a tree, is a magical moment that cements Tarkovskys arrival in the cinematic universe. The rest of the film unfolds in a ominous manner, trudging through swamps and forests as the resilient Ivan becomes uncertain of his fate. The film garnered high praise when it was released, winning the Golden Lion from the Venice Film festival. In an odd way, Ivan’s Childhood is perhaps Tarkovsky’s most accessible film thanks to its straightforward narrative and brisk pace, while also putting on display the staples of what would become his distinctive style.

In 1965, Tarkovsky directed perhaps his most ambitious film for his motherland Russia that ironically was not released and censored due to its controversial subject matter, Andrei Rublev (otherwise known as The Passion of Andrei). Proposed to Mosfilm during the making of Ivan’s Childhood, Tarkovsky wanted to literally paint a portrait of one of Russia’s greatest 15th century icon painter as a ‘world-historic figure.’ He also wanted to use his life and religious struggles as a way to reflect ‘Christianity as an axiom of Russia’s historical identity.’ The film deals with the concept of art from various perspectives while creating an unbelievable mood of what life must have been like during 15th century Russia. It’s less concerned with traditional accounts of historical facts and more about culture, artistic freedom in the face of authority and how time shapes character. The final sequence deals with a village casting an iron bell, a true test of faith for Rublev that serves as a metaphor for the larger themes in play. The original running time clocked in at 205 minutes and while the film was banned in the Soviet Union for its overtly religious themes, it did play at the Cannes Film Festival, where it won the international film critic award.

In 1972, Tarkovsky went all out sci-fi by adapting Stanislaw Lem’s novel Solaris. The psychological drama about a scientist struggling to find his sanity aboard a space station seemed initially like an odd fit for the meditative filmmaker, but Takovsky had reasons for wanting to make the film. In addition to admiring Lem’s work, Tarkovsky needed to have a financial hit, since Andrei Rublev had gone unreleased and was considered a financial disaster. Since the book was revered by many, the source material would appeal to a broader audience. However the vision for Solaris that Tarkovsky portrays is somewhat at odds with its source material, with Lem famously saying he ‘never really liked Tarkovsky’s version.’ Perhaps that because it’s uniquely Tarkovsky and displays an evolution of an auteur in the making, putting his cinematic stamp on Lem’s material. The film reflects on themes of nature versus the cosmos and the universal desire to explore the reaches of space. It’s also a fascinating comparison piece to Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, which revels in the unknown limits of the universe whereas Tarkovksy yearns to return to Earth. It won the Grand Prix in the 1972 Cannes Film Festival while also being a successful financial hit. However, Tarkovsky cites the film as ‘an artistic failure’ in the documentary Voyage in Time.

From 1973 to 1974, the filmmaker decided to turn the camera on his own inner psyche by making an intensely personal film The Mirror. Drawing on memories from his childhood, the film is a turning point for the director’s immense defiance of traditional cinematic style. Mixing in newsreel footage, poems by his father and rhythmic slow camera movement, the film plays like a stream of consciousness, accentuated by sounds of nature and haunting dream sequences. The concept was one that the filmmaker had been working on for a while, having rewritten the script several times under different titles. It’s undoubtedly the most personal film Tarkovsky ever made, as well as one of his most complex. Because the film is experimental in nature, it was rejected by the head of the studio which infuriated Tarkovsky. The film was not allowed to play at Cannes and had a limited release, despite being praised by audiences.

These problems would only get worse with his next film, Stalker, a return to the sci-fi genre. Loosely based on the novel Roadside Picnic, the story deals with a trio of metaphorical characters wanting to access a mysterious Zone where your innermost dreams can come to life. The Stalker serves as a guide to the Writer and the Professor as they take a metaphysical journey from a fascist neo-future to a nature sanctuary of surrealism as only Tarkovsky could do. It also eerily foreshadows the Chernobyl disaster that happened seven years later, which created a ‘zone of Alienation.’ Further evolving from the style of The Mirror, Stalker is also beloved by many as their favorite Tarkovsky film for its mystical cinematography (switching from brown monochrome to vibrant color), trippy soundtrack by Eduard Artemyev (who also scored Solaris) and mind bending mise en scene. Yet the film was mired with production problems, including losing almost all exterior shots due to a bad negative. The film was the biggest financial hit of Tarkovsky’s career, despite the last he would shoot in his motherland of Russia.

In 1982, Tarkovsky travelled to Italy to begin work on Nostalghia, his first non-Russian language film. The film further continues to showcase the maturity of Tarkovsky’s approach to memory, while also connecting heavily themes of Christianity. In many ways, Nostalghia is perhaps most similar to The Mirror because of its reflective nature and portrait of someone posing questions about creative freedom. The main reason Tarkovsky chose to make the film in Italy was because of previous attempts by studio executives and even government officials to censor his material. With Nostalghia, Tarkovsky bares his soul by combining iconic Italian landmarks with hypnotic cinematography that creates an amazing sense of spirituality. There is a 63-minute documentary Voyage in Time which documents the travels in Italy of the director himself. The film won several awards at Cannes but was not allowed to win the Palmes D’or by Soviet officials, further hardening Tarkovsky’s resolve never to return to his homeland.

In 1985, Tarkovsky would travel to Sweden to shoot his final film, The Sacrifice. Working with Ingmar Bergman’s acclaimed cinematographer Sven Nykvist and actor Erland Josephson, the director used a translator to direct a Swedish cast and crew. In this final mediation on life and death, the plot centers around a family of people living on a desolate island in the throes of a nuclear apocalypse. The film deals with the struggle of coming to terms with sacrifice and what is sacred. It’s meticulously shot with Tarkovsky’s trademark slow movements, the opening scene lasts 9 minutes in one single take. There is an incredible story about the climatic scene of the film where the principal house the family has been living in burns to a crisp. The production suffered a crippling camera failure during the filming on the crucial scene. Devastated, Tarkovsky was ready to give up all hope when the crew decided to pull together and rebuild the house (documented in two documentaries Directed by Andrei Tarkovsky and One Day in the Life of Andrei Arsenevich). What they captured the second time around will forever remain one of the greatest moments in cinematic history. Unfortunately, the director would not live to see the film play publicly and died of cancer shortly thereafter.

It’s hard to describe what makes Andrei Tarkovsy such an important figure in the canon of film history without seeing one of his films. Suffice to say he has been a clear influence on countless filmmakers, each of his seven films offering a different context to the auteur’s life. In many ways, every film represents a chronological growth of Tarkovsky as a human being, as an artist. Ivan’s Childhood is him stepping into the light of the world; Andrei Rublev is his dedication to art; Solaris is his reflection on Earth; The Mirror is the reflection of himself; Stalker is his rebellious side; Nostalghia is his dedication to Christianity; The Sacrifice is his final statement of the inevitable fate. And while these are just personal extrapolations, it’s also what gives Tarkovsky’s body of work such richness of life, in the discussions it evokes and the questions that arise. While his films require a patient mind to be appreciated, Andrei Tarkovsky’s filmography offers a unique glimpse of a distinct artist that defined a poetic style of filmmaking that is both wondrous and haunting to this day.

Additional Resources: Sculpting in Time, Andrei Tarkovsky Interviews, Collected Screenplays of Andrei Tarkovsky, Instant Light: Tarkovsky Polaroids