Valentine Road, directed by Marta Cunningham, is a challenging piece of documentary that forces you to look at prejudice from several different angles, and look at the men and women who represent such feelings of hate.

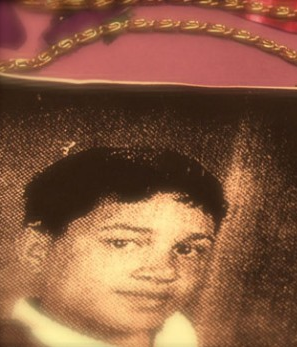

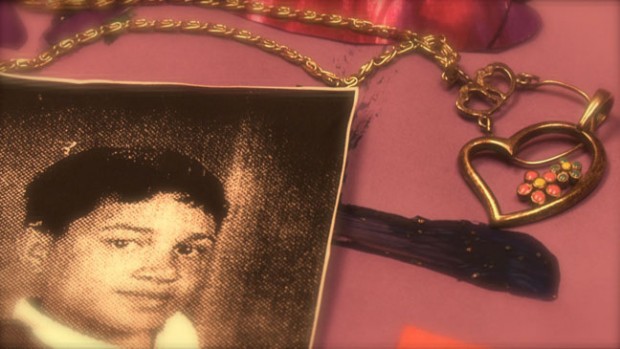

The doc digs into the murder of Lawrence “Larry” King, a small 15-year old Latino boy who liked wearing women’s clothes and women’s make-up to school, and Brandon McInerney, the troubled 14-year old who shot him in the back of the head.

We open to a recount of the event from those who were in the classroom when the shots were fired. Friends of Larry weep over his death, as does the teacher who had supported Larry’s fashion habits the weeks up until the shooting. Then we meet Brandon’s mother, brothers and his girlfriend Samantha, who all mourn over the loss of Brandon, now facing life in prison because it has been decided he is to be tried as an adult.

And so begins an organic examination of intolerance, which grows like a weed after the trigger has been pulled. The town of Oxnard, California, where the murder took place, slowly reveals itself to be the lead character in this documentary, a place full of people who become certain that Brandon McInerney should not be tried as an adult, but rather as a confused kid wo was being provoked by a flamboyant gay kid. That he went home, took one of his grandfather’s firearms, and woke up the next morning planning to kill the young man is glossed over by this lot, convinced the law in California, which has allowed Brandon to be tried as an adult, must be fought against. They also mention the fact that Larry had asked Brandon to be his valentine in front of all of Brandon’s friends, an act of humiliation that could explain why Brandon blew a hole through Larry’s head.

To be sure, Brandon’s childhood was a tough one, full of all of the horrors and nightmares no parent would ever wish on their baby or the baby of any other. Brandon’s mother explains herself and the actions of her abusive, addict husband Billy throughout, tears in her eyes and guilt flush throughout her face. An addict herself, we watch her hold one of her older sons in an interrogation room, asking God why her son Brandon would do such a horrible thing.

Cunningham does a superb job at finding the humanity in everyone on screen. There’s a painful familiarity to those in town – and throughout the country, in fact – who believe that Brandon’s premeditated actions are somewhat explainable because of the sexual orientation of Larry King. We all know people like this; people who allow their quiet bigotry to seep out in moments like this. A glass of wine in her hand, one woman suggests that if she were Brandon and someone like Larry was coming on to her, she might not shoot the kid but could understand it. Brandon’s girlfriend Samantha explains how Oxnard used to be full of white people and now it is not; she explains how that’s not a bad thing, just hard to deal with. As we listen to her calm words of separatism, we see the woman she will become. The woman with the glass of wine in her hand, trying to explain how premeditated murder can be justified if homosexuality is involved.

Thankfully, Cunningham is presenting these people and these views to us, rather than lambasting them. That she leaves to us.