Spike Lee is an honest original, warts and all. Over the last two-and-a half decades he’s made the films he’s wanted to make the way he’s wanted to make then. And when he couldn’t get the money to do one project in particular – Malcolm X – his friends and fans came through and helped get the film made.

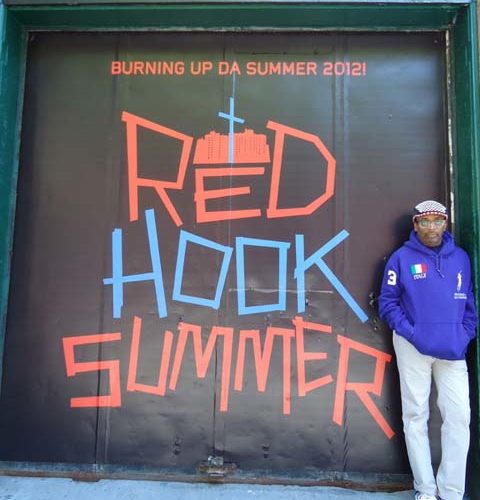

His last feature was the immensely-flawed war film Miracle at St. Anna, followed by a 4-year hiatus from fiction for the accomplished filmmaker. Now he’s back with Red Hook Summer, doing what he did so well over 20 years with Do The Right Thing: painting a portrait of a neighborhood, and building from there.

This time, instead of Bed-Stuy, it’s Red Hook, an old port town on the very west side of Brooklyn. The small town represents a part-conceptual sequel to Right Thing, part-coming of age tale, part-criticism of the Establishment through the lens of religion and much, much more.

Too much, in fact. Like many of Lee’s films, Red Hook Summer is constantly biting off more than it can chew. Though it opens as a somewhat nostalgic nod to the neighborhoods that Lee found his art in, including beautiful establishing shots of Red Hook and its cast of characters, the film quickly dissolves into an somewhat coherent rant including Mr. Lee’s biggest problems with America. Now, to be fair, most every of his is that on some level. This is the hyperbole.

Clarke Peters (you know him as Lester Freamon from The Wire) navigates the messy narrative without breaking a sweat. Lee has introduced one of his most complex characters in Peters’ Bishop Enoch Rouse. On the rocks with his daughter, he’s determined to convince his grandson Flick Royale (Jules Brown) to find God in his church, Little Heaven. Unfortunately, Flick just wants his school-free summer. Thankfully, a cute girl his own age, Chazz Morningstar (Toni Lysaith), also attends the church, giving Flick a reason to alternatively obey and rebel against his grandfather.

Judith Hill does the film a lot of favors with her obtrusive yet immensely engaging score, very much in touch with the gospels Bishop Enoch preaches throughout. Much like the bishop’s faith, Hill’s music is never far away. God has never played a bigger role in Lee’s world. Here the entity serves as both hero and villain.

As the story progresses – after a long-winded hour and a half – the central question of the film finally rears its ugly (and it’s ugly) head: how good is God if everyone, even the bad people, can rely on him? Flick can’t find the answer from his grandfather or his inexplicably absent mother (the motivation behind his mother sending her son away to her estranged father is never touched on, one of several aggravating plotholes).

Brown and Lysaith are the leads of the film, which is a refreshing change of place as child actors are usually relegated to supporting gags. However, this blessing is also a curse, as some scenes of dialogue between the two read under-rehearsed and overly-scripted, as if these young performers were trying to remember their lines as they are being filmed. Yet, for every one of these unreal scenes, there are two that feel genuine.

Lee also offers his fans some nostalgia, reprising his role as Mookie from Do The Right Thing with the appropriate pomp and circumstance (i.e. one particularly charming pizza pie-holding scene). There’s also a bevy of street-preachers akin to those in Right Thing, including Mother Darling (Tracy Camila Johns) who feels like a descendant of Ruby Dee’s Mother Sister. And then there’s a particular ridiculous, unnecessary and aggravating reference to HBO’s The Wire. But, as with the young leads’ performances, Lee’s passion vastly outweighs his self-indulgence.

One wonders who will buy and distribute such a film, which asks very hard questions so explicitly. It seems Lee doesn’t care. The filmmaker, once again, has made exactly the film he wanted to make.