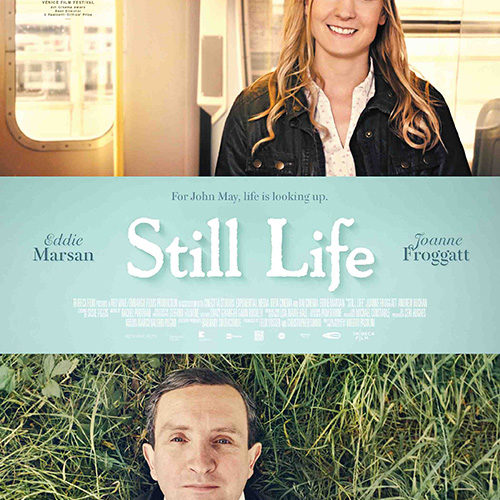

Oscar-nominated producer (for The Full Monty) Uberto Pasolini‘s second film as writer/director isn’t easily categorized. Aptly labeled with the hybridized compromise “dramedy,” distributor Tribeca Films for some reason has attempted to also pitch it as a bit of a romance with both their current trailer and synopsis. This is a very misleading maneuver in hopes of selling a quiet, contemplative work to the masses looking for more than an existential cinematic poem. But that is exactly what Still Life is at its core: a glimpse at the question of who we are and whether or not we remain relevant after our deaths. So many are quick to agree that there’s nothing left to be done for a person after he’s taken his last breath. A select few like John May (Eddie Marsan), however, know that’s hardly true.

A caseworker who’s spent the past twenty-two years researching the next of kin for hundreds of deceased bodies left alone and often forgotten, it’s not lost on us that the work he completes ultimately places him in a similar spot as his subjects. Pasolini goes to great lengths to show how much of a creature of habit his character is from a simple dinner of tuna and toast to the obsessive compulsiveness of his actions at the office and at home. He’s meticulous in his bookkeeping, nostalgically compassionate in saving a photo for every person he personally succeeded or failed in securing relatives for their funerals, and an introverted loner whose interactions with the living consist of generic platitudes and awkward silences. If he were to die today he’d most certainly become the first case for his replacement.

To John, these abandoned souls are friends. They are people he can be quiet with, puzzles he can journey to solve, and conduits for beautiful stories hidden beneath the usual rough paths and missteps each took to find themselves alone at their deathbeds. It seems he rarely if ever convinces anyone to see their passed friend or family, each ceremony of remembrance attended by the priest/rabbi/etc and only he. John crafts poignant eulogies of half-truths and speculation culled together from the things left behind—kind words to give each soul a goodbye his boss (Andrew Buchan) would rather prevent in lieu of a cheap cremation and communal burial plot for multiple urns of dust to collect. John serves as their guardian angel of sorts, an optimistic champion of hope and stalwart companion to the end.

It’s appropriate then that his final case—the council has cannibalized his position with another occupied by someone far less discerning in the disposal of unwanted remains—would hit so close to home. And I mean figuratively and literally considering Billy Stokes’ body was found in the apartment across the courtyard from John’s own. It had taken forty days for someone to finally notice the odor and call the superintendent. A month and a half where not one single person missed the man left motionless inside. Stokes could easily be John and the thought of dying so that only his successor at the council would stand at his funeral (if she even let him have one) is too tough to bear. It therefore becomes his mission to find anyone to honor Billy as he’d hope someone would him.

For a man who eats his apple the same time every day, hangs his coat on the same hanger behind his door at work and home, and sits in silence until able to do it all again, the adventure of finding Stokes’ daughter (Joanne Froggatt‘s Kelly) is rejuvenating. Billy becomes a hero to John—the best friend he never had—of which he can live vicariously through posthumously. Stokes wasn’t universally liked nor someone able to check “no” on a job application when asked if he’d ever been in jail, but he had his moments with many people who genuinely procure a smile at the mention of his name. None of them may be willing to revisit the life they spent with him over a decade previous to attend his funeral, but their remembering is perhaps better.

Still Life therefore becomes a document of how far our reach goes as individuals. We may not believe we have accomplished much or touched people in a way that would give them pause upon learning we have passed, but there is always someone with which we’re able to live forever. Is it any less miraculous when that someone is a complete stranger such as John compiling his scrapbook of the forgotten he looked over? Is the job he served any less fruitful when he cannot find anyone who knew the deceased or perhaps worse finds that they want nothing to do with him/her? There’s a stunning beauty to the humanity Marsan displays in his portrayal of May; a saintly selflessness in his quest to prove no life is worthless—especially not his own.

A glimmer of romance does appear once he finds the kind and sensitive Kelly via a trail of breadcrumbs putting his detecting skills to task, but her introduction isn’t until over halfway through the film. And even then Froggatt earns at most fifteen minutes onscreen. She does play a very integral part of John’s unlikely evolution into an empowered being ready to take on the next chapter of his life with eyes open and oxygen in his lungs, but it’s less about her role than her effect. We all vainly wonder how many people will show at our own funerals—well everyone except John. He’s given countless strangers the goodbye they deserved, enough so that reciprocation will arrive from the afterlife if not Earth. The purest of souls never seek reward yet always prove rich nonetheless.

Still Life is now in limited release and on VOD.