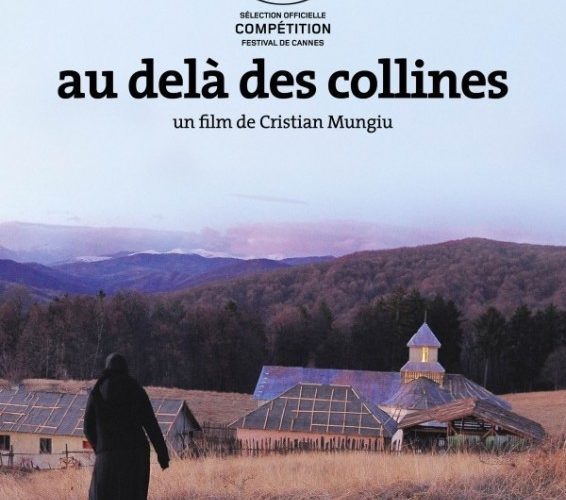

Romanian filmmaker Cristian Mungiu is undoubtedly a Cannes darling, with his debut feature film Occidental having premiered in the Director’s Fortnight in 2002 and his follow-up 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days taking the Palme D’Or in 2007. In his third film, Beyond the Hills, the director attempts to tackle the universal subject of faith and love in an unusually particular manner. Using his trademark single-take shots for each scene and completely devoid of any music, the film plays out like a solemn sabbatical about the hardships of committing oneself completely to God. Despite the promising approach to a controversial issue, the film is a chore to sit through, reminiscent of a child bored in Sunday school.

The film opens with a solemn tracking shot of Voichita (played by newcomer Cosmina Stratan) a nun from an orthodox monastery picking up her childhood friend Alina (played with silent brutality by another newcomer Cristina Flutur) at a crowded train station. This moment of chaotic normalcy in a public arena is quickly snuffed out by the quiet prayer of a church beyond the hills of the local town. It becomes quickly apparent that Voichita and Alina were lovers at the orphanage where they grew up together, and Alina desperately seeks this kind of affection from her former flame. But Voichita has committed her life and her heart to God and hopes to convince Alina to do the same.

Mungiu has a clear intent to build up an atmosphere of dread, as concepts of good and evil are thrown into the balance under the spotlight of religious dogma. As the long-bearded priest (played with detached frigidity by Valeriu Andriuta) challenges Alina’s intent for being in the monastery, it leads to questions about the sanity of her soul. Tensions mount slowly, partially due to the nature in which Mungiu presents each tableaux, with an unflinching austere quality. It’s almost like a Romanian version of Arthur Miller‘s The Crucible mixed with the slow pacing of the eastern Europe cinema.

However, the effectiveness of the film’s ultimate message could have been achieved more cinematic punch had Mingiu reduced some of the overly-indulgent redundancies.

Questions of faith versus love have been interesting fodder for debate since the advent of Christ and while this tale could be compelling, the detached nature of the direction leaves you frozen with lackadaisical impunity. Perhaps the intent is to force audiences to question what is faith in the face of love, or put doubts about our own personal beliefs. But it’s hard to connect with a culture so out of touch with the logic of present day and scenes that linger on for far as too long further distance the ambiguous themes. While it’s easy to see the rationale behind Mungiu’s religious critique, Beyond the Hills cannot find salvation or redemption in the conflicts of it’s characters’ tribulations.