The films of Alice Rohrwacher have always been rich with the sensory magic of growing up, but that atmosphere has, up to this point, been enhanced with the knowledge that puberty was approaching, just out of sight, with all the subtlety of a B52 bomber. With her newest, Happy as Lazzaro, she has largely forgone that period of adolescence, while somehow not forgoing that sense of everyday magic. What emerges is not simply a next step in her oeuvre and creative growth but a fully formed expression of her virtuosic talents.

We shouldn’t make such grand gestures, however, without clarifying that none of this would have been possible — at least not in such a realized way — without the symbiotic artistic partnership she has shared with Hélène Louvart, cinematographer on all of her features to date. Working with gorgeous super 16 (complete with rounded screen corners and glorious imperfections on the peripheries), Louvart’s eye seems once again drawn to that everyday magic as she continues what has become an obsession with the play of interior light. We open on a moment that perfectly expresses both that obsession and their creative relationship as a group of girls jostle over one of the family household’s two shared light bulbs, a moment that perfectly echoes back to the spinning lampshade in Rohrwacher’s debut, Corpo Celeste. It’s eventually put in and, well, like a light, we enter their world.

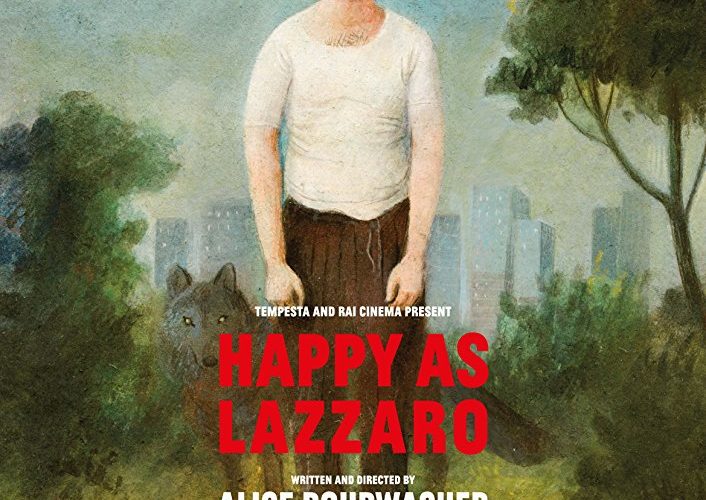

The film follows a young lad, Lazzaro, who works for the large peasant family of which these girls are a part. Played by newcomer Adriano Tardiolo (an exceptional discovery), Lazarro has the short, stocky build of a college wrestler, a gait best described as endearing and the sort of wide, searching brown eyes worth getting lost in.

We’re somewhere in the 1980s. Lazzaro works for a family who themselves work the land for a local tobacco giant with the inauspicious title of the Marquis De Luna. The Marquis chain-smokes cigarettes, of course, and so her son does, too. This boy, Tancredi (Tommaso Ragno), arrives on the plantation like a visitor from Mars: pale, skinny, and with just a hint of the Draco Malfoys, his hair, Walkman, and fashion the embodiment of a faster world. He’s brash but not a bad skin, as it turns out, and, much like us, seems immediately taken by Lazarro’s kindness, innocence, and sincerity (perhaps his beautiful brown eyes, too). The boys form an unlikely bond. When Tancredi runs away from home to hide in the hills, Lazarro begins to skip work in order to bring him food.

What happens next should probably not be elaborated on too much. Suffice it to say there is a suggestion of romance; then a shock; then a jaw-dropping touch of Deus Ex Machina. The screenplay, at this point, is only about halfway through, and while Rohrwacher executes the shift with total fluency, it is nevertheless still difficult to think of a more radical narrative handbrake turn in recent cinema. We should probably leave it at that.

You could argue that Happy as Lazzaro owes a debt to Pasolini with its fascination for peasants, saints, and faces, or even Gabriel Garcia Marquez with its mix of rural life and magical realism, but that would be to discredit the shear vivacity and boldness of Rohrwacher’s directorial hand, not to mention her incredible warmth as a filmmaker. Indeed, nothing ever feels labored or out-of-place here, not even when a church organ’s keys go silent as the music being played, as if carried by the hand of God, departs the building. These moments are not only beautiful in their conception; they somehow enter and enrich the fabric of the film without jeopardising any of its more straight-faced messages about class and Italian socialism (not to mention the audience’s enchantment, too).

As in her last film, The Wonders, such moments of supernatural catharsis work because the world around them feels so authentic and lived-in. Alice and her sister, Alba Rohrwacher (a tremendous actress who once again features here), were born to German and Italian parents in Northern Tuscany, and though her father was a beekeeper by trade (as referenced in The Wonders), you wouldn’t necessarily call them working-class. Nevertheless, the sense memory of that life and that time seems perfectly encapsulated and true.

The poor farming class in Lazzaro are shown as kind and honourable but also gullible and understandably uneducated, too. This might come across as somewhat condescending were it not for the fact that Rohrwacher portrays them with such tremendous warmth as to suggest that Italy should be ashamed for forgetting these people. Indeed, the message of her boundless, beautiful new film might be that Italy is these people.

Happy as Lazzaro premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and hits Netflix on November 30 . Find more of our festival coverage here.