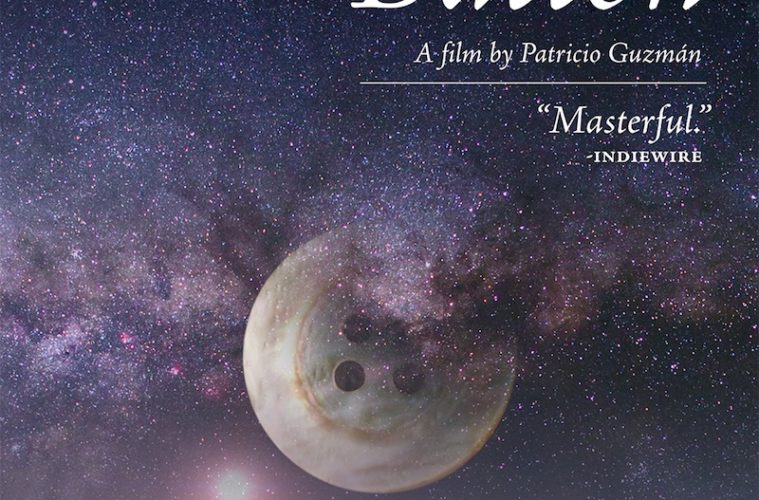

There’s the temptation to throw out a big, (somewhat) cheeky comparison and say we’re looking at the most existentially heavy and historically dense film about water since Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia, but that doesn’t quite do. The Pearl Button, for every comparison it invariably raises — a splash of the great Russian here, a dash of Godfrey Reggio there — doesn’t fit into many pre-existing frameworks. This is a film that speaks for itself while standing for many things: science, history, the mysteries they create, and the extent — for better or for worse — to which cinema can represent them.

It should go without saying that Patricio Guzmán hopes to fit a fair amount into the 78-minute runtime, and the fact that he so often succeeds thus means that, in total, this picture’s greatest achievement is rarely being weighed down. The stream-of-consciousness mindset that propels Button – one where his ever-present voiceover is less a reinforcement or explanation of the presented images, more a means of following stray thoughts – will invariably create sections that are more engaging than others; whatever flaws that connotes, it testifies to not just an ability, but a willingness to reorient itself. A “testament” if you’re a fan of such projects, that is.

What begins as one man’s contemplation of the universe’s massive scale – most of all, Guzmán ponders what might be made of the many distant planets that Chilean satellites find on a daily basis – shifts into a study of water. A subject so broad and so all-encompassing will require more than one voice, and here he concedes the platform, turning to experts who can contextualize this material into digestible forms. But two things are happening here: for one, their own interpretations have a bit of the dumbfounded quality to them (“Everything is water” is offered as a more-or-less-complete statement); and Guzmán can still be felt behind the camera, speaking for how everything is presented, mediating every image and sound to a personal preference. His experiences and moods will continue to be The Pearl Button‘s crux, making this the rare essay film that not only adheres to the absolutes of science and history, but finds a way to make them part of its special fabric.

Take, for instance, a section detailing the white influence on Chile’s civilizations, the way the natural and “current” (for wont of a less-punny term) sound of flowing water floats over archival photos. This is more than a simple gesture that bridges a bygone era and our own, or what we perceive as being part of our own; it’s instead part of a mission statement that treats these atrocities as an absolute, in some ways more concrete than science itself. (It’s spoken of in more resolute terms, for one thing, and Guzmán’s only change of tone — to anger, naturally — is palpable in as little as slight vocal shifts.) Mourning leads to contemplation; contemplation leads to philosophical inquiries; philosophical inquiries turn him toward science; science makes way for history. This is The Pearl Button’s cycle.

As has been alluded to, his narrative is not consistently engaging — a quality that owes something to the multiple angles being reached toward. Ambition that creates a faltering can always be admired, however, more so when it allows the gears to shift into, of all things, a crime movie. The detailing of a barbaric killing practice enacted by members of his country’s government extends Button‘s ideas and inquisitive tone into a new realm, one that, you’d expect, is downright unpleasant. A morgue’s file photo of a woman who’d been killed is presented to us in such a way that we’re initially shocked, then almost immediately forced to ask two things: if we stare or look away, and why we choose to do so. Guzmán doesn’t necessarily underline this idea; it’s simply a part of the picture’s fabric.

So, yes, The Pearl Button can sometimes prove more interesting to consider than to actually watch, but those moments it truly comes alive — when it comes alive as something that wants to consider factual absolutes within psychological parameters — are compensation enough. In a year with no Malick films and a general dearth of some proper essay picture, this shows that great surprises are sometimes peek right around the corner.

The Pearl Button begins a limited theatrical run on Friday, October 23.