When little Carol Ann Freeling ominously intoned ‘They’re Here!’ in 1982′s Poltergeist, she wasn’t just announcing the fact that ghosts had discovered suburbia, but that the new overseers of blockbuster filmmaking were finally appropriating the supernatural horror genre. When Steven Spielberg and Tobe Hooper moved the classic tropes of the ghost story to the land of mirror-image housing, Reagan-era values and burgeoning baby-boom anxieties they poured the haunted foundation for what would become the current blueprint of the sub-genre. Now, we’ve finally arrived at the inevitable moment when the original must pay the piper for its iconic trailblazing and receive its own remake. Fortunately for Poltergeist, you could do a lot worse in this department than Gil Kenan’s amiably pleasing little spook show.

In the few years prior to the original Poltergeist, the haunted house motif was still enjoying relatively classical interpretations with the likes of The Shining, Ghost Story and Peter Medak’s The Changeling, whose most turbulent supernatural image was George Scott bellowing at the unseen phantom that dared roll a toy ball down his staircase. None of those movies would have even conceived of the Spielbergian sound and fury that closes Poltergeist, with the offending house itself literally pulling up its roots and imploding into some other misbegotten dimension. Special effects and visceral evocation overtook a venue that had largely depended on atmosphere and suggestion, and not all the films that followed Poltergeist were as adept as marrying their human elements to the spectacle. When that original movie ended, it left us with the disconcerting revelation that the suburbs weren’t just haunted, they might actually be spiritually unhealthy for us with their soulless sameness and downsized ambitions. The filmmakers were addressing the body-snatching makeover of our personal lives, but did they for-see the identikit 3D horror pictures of today? Would they have shuddered at what was wrought?

Either way, like it or not, here’s a new Poltergeist, calling itself a reboot but feeling for all the world like a mostly literal remake of the 1982 picture that shuffles a few of the themes and concepts but ends up looking like the same house, mildly remodeled. The new family that moves into the paranormal epicenter of the neighborhood is The Bowens, whose arrival here signals their movement down the financial ladder, trading up a higher class of living due to the recession. Unlike The Freelings, whose shiny new home in Cuesta Verde was one of the signposts of patriarch Steve’s career success, The Bowens aren’t experiencing the affluent haze of the American dream. Eric (Sam Rockwell) has been laid off for some time and troubles finding a new job have left him listless and frustrated, his wife Amy (Rosemarie DeWitt) is a would-be novelist struggling to hit that sweet note that would help lift the family out of peril, and their kids, teenage Kendra (Saxon Sharbino), pre- adolescent Griffin (Kyle Catlett), and 6-year-old Madison (Kennedi Clements) are still reeling from the upheaval of their old lives. The signs that the house is sinister start early here, with tree branches automatically receding into the earth, a box of extraordinarily creepy dolls appearing in the attic, and a dinner party conversation that casually drops the words ‘tribal burial ground’. In an intriguing development, the daily struggles of the Bowens are initially more compelling than the echoes of supernatural malice.

Finally, there’s the pivotal sequence that launches the film forward; Eric and Amy are away at dinner, and the children fall prey to a trio of unearthly invasions, involving creepy creatures in the basement, the hijiinks of a particularly malevolent tree, and a spectral abduction that manages to be harrowing in the same way its predecessor was. Maddie is now trapped in a spiritual dimension beyond the Bowens grasp, held hostage by whatever forces are using their home as personal puppet theater. Gil Kenan, whose Monster House was a delightful ode to that transitional time in 80’s cinema that melded the wonder of Spielberg with the eccentricity of Tim Burton, handles these scenes remarkably well. His visual aesthetic and scene construction brings a certain value to the perspective of the kids, who get to have their own internal reactions and opportunities for heroism that were denied them in the first film, which, to be fair, was mostly the story of their parents. Screenwriter David Lindsay-Abaire builds a plausible and endearing dynamic, drawing off the first’s most definable trait, its portrait of familial solidarity in the face of the unknown and unimaginable.

The unknown and unimaginable get pretty well imagined here, thanks to the advancement in special effects since 1982, and even though the first go-round was no slouch in the supernatural action department, Kenan’s picture takes it to another level. Hooper and Spielberg had some large scale set pieces to deploy and limitations in what they could and couldn’t show, so the first film used brilliant editing and composition to give the illusion of consolidated paranormal phenomenon that felt like an escalation event. Here, the camera glides smoothly around the fantastical compositions and towards the climax, gives us a full-fledged visualization of the world beyond ‘the light’. This particular manifestation is imaginatively creepy, drawing from medieval visions of limbo and purgatory to furnish an afterworld far more satisfying than the spasming phantasmal hulla-balloo of Poltergeist II’s version of the same place.

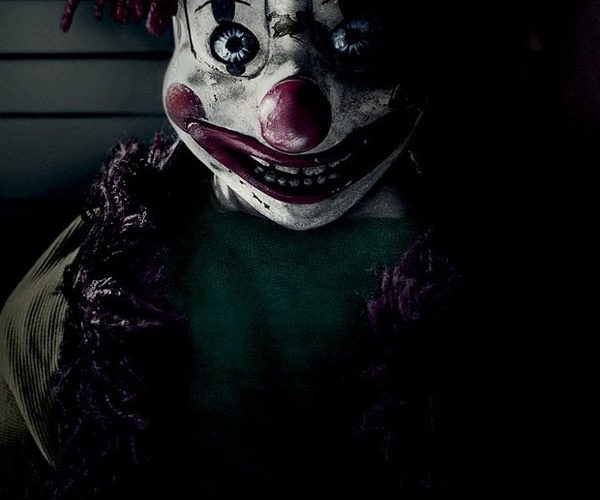

The critters aren’t quite as effective this time through, and that includes the evil little clown that attacks Griffin. That first doll was a mostly normal, vaguely threatening little ragamuffin, while the new iteration looks like Annabelle’s circus-bound son; the clown has been so overdesigned that he becomes less instead of more scary. He’s clearly a horror-movie creature that wouldn’t exist outside a film, anddoesn’t have the same effect a more benignly real creature would have when it begins to do things it shouldn’t, like throttling you in your sleep. The hauntings, while specatcularly realized, never have the same troublesome impact when they occur, partly because we are never quite as connected to the characters. Maybe, too, it’s because we’ve already seem them before.

Effects aside, Kenan’s film would barely get off the ground without his actors, who don’t have the same richness of depth to work with that relative newcomers JoBeth Williams, Craig T. Nelson and Heather O’Rourke had. Rockwell gives another strong and human performance and its starting to feel unlikely that he ever gives otherwise; Eric is a more fragile creature than Nelson’s straight-forward Steve, but the actor finds some potent compartments of both humor and fear. His breakdown once he realizes his daughter may be beyond his reach is overwhelming and poignant. DeWitt does nice work echoing Williams’ harrassed stay-at-home mom who will cross whatever dimension necessary to rescue her children. I liked best Catlett—who is left with real guilt about his inability to save his sister—and Clements as Madison, who gives a believably sensitive turn that references but doesn’t coast on O’Rourke’s performance. All of them come together and convince us they are a real family operating in an surreal situation.

Perhaps the trickiest part of the new Poltergeist is getting right the attempted rescue mission to the other side, because in the older film, that sequence was the unmistakable emotional centrepiece of the whole thing. Pivotal to its effect was Zelda Rubinstein’s Tangina, the psychic who’s called into help the Freelings. Diminutive yet commanding, Rubinstein came off as such an original and ennervating force that her 15-or-so minutes of screentime dominate the entire film. When she speaks the lines “To, her it simply is another child. To us, it is the Beast”, she etches a portrait of malevolence that outdoes the later physical manifestations we see. Kenan knows she can’t be replaced so closely to the source, so instead we get Jared Harris—who did something similar but less effectively in last year’s The Quiet Ones—as legit TV ghost hunter, who’s brought in by Jane Adams’ parasychologist. In a tip of the hat to The Conjuring, Adams turns out to be Harris’ ex-wife, and some of their mutual sniping adds some welcome amusement. Harris and his lilting Irish accent make this new character more of a showman than anything, although uncertainty in his ability lurks at his borders.

The new Poltergeist is, in its own right, a fine film that does just about everything the target audience will be looking for it to do. What’s interesting is that Kenan and his team conduct themselves so well that instead of justifying their remake, they only solidify a case against its existence. This movie borrows so much imagery, atmosphere and theme from the first picture that it ends up rendering most of its intended shocks toothless and its conceits tired instead of novel. Carol Ann being swallowed by the television was an original and very clever way of drawing out that underlying fear of an entire generation of children discarded to the babysitting care of the tv set. The original film so expertly played that note because it had the responsibility of its creation; the new movie is only playing riffs on an existing theme, so there’s less danger, less tension, and ultimately less impact. After watching Poltergeist 2015, it’s clear that Kenan and all involved could have made an entirely original work that could stand on its own. Instead they’ve cut the same corners as those morally questionable real estate developers in Cuesta Verda, building their enterprise on the restless spirit of a force that will inevitably come back to haunt them.

Poltergeist is now playing in wide release.