“I don’t know why death is always the same, but it is,” cryptically muses Peter Dunning, the owner of Vermont’s Mile Hill Farm, after he’s slaughtered a sheep. In Peter’s 38 years running the organic farm, he’s seen three wives and four children come and go. He hasn’t spoken to them in nearly two decades. His speech patterns buzzing with homespun philosophy, Dunning compares his farm animals to prisoners, saying that he’s spent enough time in jail to know what that must feel like. At the farmer’s market, when you imagine who’s growing the organic vegetables, you’re not exactly picturing a borderline hermit like Dunning. He even writes carefully worded letters to the editor of his local newspaper, which he’s outraged to find published in edited versions. Dunning drinks and curses and rages at the camera, daring the audience to look away.

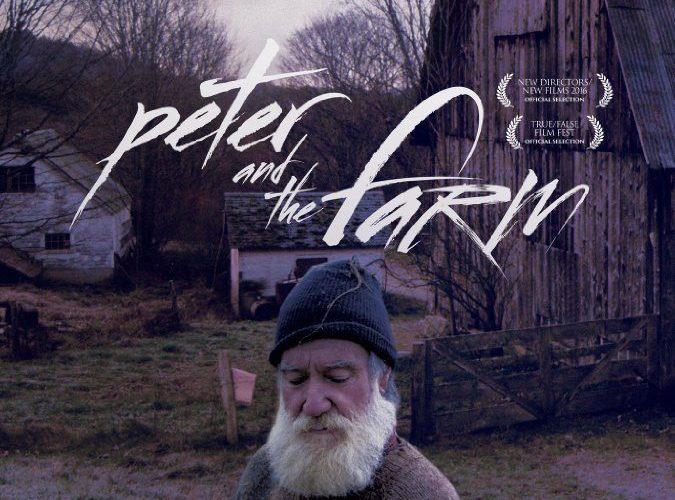

Peter Dunning is an unhappy man, and Tony Stone’s documentary, Peter and the Farm, demonstrates how interesting and romantic melancholia can appear from the outside. It’s a fleetingly kinetic portrait of an American life. Like the man, the film is all bark and not much bite.

After meeting Dunning and his farm, we’re permitted a peek inside his art room. He’s also an accomplished artist and painter. Embarrassed yet intoxicated by his artistic side, Dunning bashfully criticizes his humble paintings just as he proudly displays them for the camera. He laments the notion that troubled times can often be the most productive and fruitful periods for artists. “You have to start wondering,” Dunning asks himself. “Are you just keeping it fucked up so you can continue making art?”

Life on the farm is tough. We’re introduced to Dunning in a scene not unlike Clint Eastwood’s introduction in Unforgiven, a grizzled old piece of granite chasing a hog around until he stumbles and face-plants into the mud. Dunning works alone, save for a farmhand who we rarely see, if ever. (It’s tricky to surmise who’s who, as the filmmakers sometimes step in front of the camera to lend Dunning a hand during muddy jobs.) The film lingers on the violence of farming — in particular, a sheep who requires not one, but two bullets to the head before it keels over. Dunning’s farmhand hides the rifle when his boss gets drunk and suicidal. The farmer’s increasingly disturbing bursts of anger become more and more frequent as filming continues.

Dunning is a top-notch storyteller, selflessly delivering us his heart on a plate. Despite his snarling demeanor, he has an acerbic and dry wit that catches you off guard. He’s worked for decades to keep the farm alive. As a 68-year-old man, he realizes that his farm may be the only thing keeping him alive, and that irony is not lost on him. His first wife died years ago. He’s spent the passing time working the farm, at one time receiving visits from his son and daughter. As of filming, he hasn’t seen his children in 19 years. As a boy, Dunning was adopted after his biological mother’s death. He had one small photograph of his mother, but it was shredded by his adopted sister after a childhood quarrel. He heard that his father may have died in a car accident in California. He never got the whole story and probably never will.

In his happiest moments, Peter was surrounded by family. During these times, the farm flourished. After their departure, the farm slid into predictable decline. The filmmakers never suggest Peter’s depression caused this decline, but we can easily draw our own conclusions. Since their departure, Dunning’s entire life has been shattered by tragedy and disappointment.

He recounts the harrowing story of almost losing his hand in a machine factory accident at 26, moved to tears as he caresses his mangled fingers. He later describes, with joyful exuberance, leading a squad of American soldiers to sing a cut from West Side Story. An evocative raconteur, Dunning tells these stories with vivid detail and nuance. The film’s episodic thrust gradually becomes hit or miss as the director returns to Dunning’s farm to continue shooting again and again. Even Dunning remarks, as he greets the cinematographers with a look of surprise, that he assumed the filming had already been completed. It’s as if Stone and company knew they had three-quarters of a good film in the can, and decided to simply keep shooting until they discovered an ending.

Dunning is a documentarian’s wet dream, as honest and forthcoming as he is eagerly collaborative, which makes for a wildly entertaining, if occasionally self-indulgent experience.

Peter and the Farm opens on Friday, November 4.