It is the little-stated, undeniable truth that critics are surrounded by nearly innumerable factors when experiencing the work they’ve been assigned to review. Presentation is rarely treated as a basic on the level of form, theme, or auteurist interest, and most mentions will come only if something had gone terribly wrong. This issue sometimes being rather important, I feel compelled to say James Gray’s The Lost City of Z is a rather forceful thing when projected on 35mm, as befits the writer-director’s wishes and with which the New York Film Festival, premiering this picture as the closing title of their 54th year, complied. I can and will compliment the movie for a number of reasons not necessarily pertaining to what material it was printed on and what machine it came out of, so let it be stated upfront that this is most likely the best (only?) way to experience what Gray and cinematographer Darius Khondji, reuniting from The Immigrant, have achieved: a film that will often truly and totally appear to have been made in decades past and just discovered today.

My notice of the increasingly rare presentation is not some means of trotting out “they don’t make them like they used to,” which stands awfully high on the list of worthless critical statements. I confess that admiration for the format and subsequent pining for its heyday had, upon first glance, a way of distracting from many other parts moving The Lost City of Z forward — among them a certain contemporary form which runs counter to cinematographic palette and early-20th-century setting. Composed in widescreen and moving with an uncharacteristic propulsiveness — a willingness to rattle around when proceedings turn tremulous and sweep in motion to its characters’ situation once action beats pick up — it boasts an approach that would feel well and truly out-of-place in what it pays tribute to.

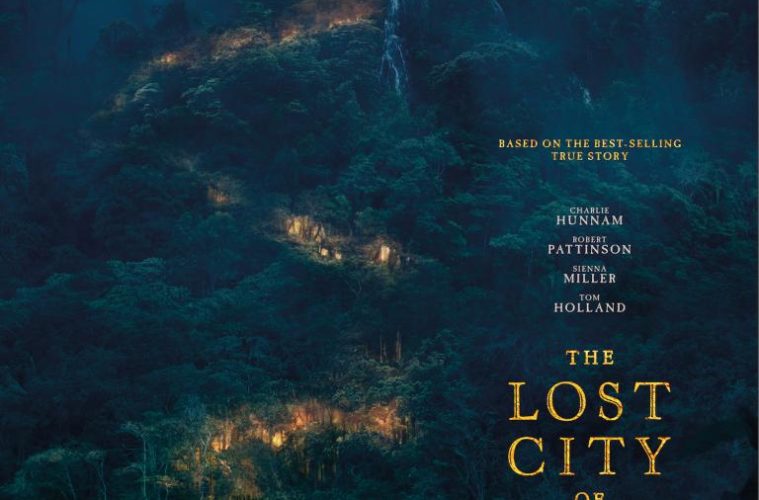

“Tribute” is not the sole, or even primary, thing on this movie’s mind, as much as it will recall many a picture before it. Lost City doesn’t even bother to stay very faithful to David Grann’s source text, a 2009 non-fiction best-seller that often situated itself with the author’s quest for the eponymous lost city. Gray almost entirely tells his own tale from the perspective of Percy Fawcett (Charlie Hunnam), an explorer who entered South America conducting cartography work for the British Empire that, per the film’s obligatory expository scene, is presented as a disguise (or waypoint) for British colonialism. (Ian McDiarmid‘s malevolent presence can only bring to mind Palpatine grooming Anakin Skywalker — but this is about as far as Star Wars comparisons will go.) Little about his mission, including the barely necessary purchase of slaves, is gussied up as noble or worthwhile, all the more so when his actual journey is set into motion with the discovery of certain items; however seemingly insubstantial (“pots and pans,” his colleagues reduce them to in a rowdy townhouse chant), they bred in Fawcett the belief that an ancient civilization’s ruins were essentially under his feet. Lo, the explorer finds his purpose.

This, mind, you, happens a good while into Lost City, which has heretofore taken time to ingrain itself in the England and, to a lesser extent, South America of the early 1900s. The movie’s not slow, but it does take some time to make do with the period’s finer points and, of course, indulge numerous dramatic possibilities. Gray’s made no secret of his admiration for Stanley Kubrick, and it would be difficult for well-acquainted viewers not to think of Barry Lyndon in an early ballroom sequence that’s adorned with baroque music, ornately dressed extras, and slow zooms — which is after an opening of horse-backing through a wide-open field to hunt and kill a buck now prominently displayed in the ballroom. Cloistered interiors and the great wide world, rough-and-tumble quests and mannerly composed gatherings — such are the binaries that The Lost City of Z wrestles with and relaxes into for its 140 minutes.

The assembled team finds plenty of space to operate within these points. John Axelrad’s editing, in its alternately porous and rigid sense of time, marks a key example: each section is demarcated by title cards noting time and place, yet within them there are flashbacks, fantasies, and, particularly, crossfades to illustrate the melting away of many hours and days spent in search of (or simply pining for the pursuit of) a goal whose endpoint never feels nearly as present as the danger created by a sonic landscape of animal sounds, footsteps, swaying leaves, and, of course, whooshing arrows often filmed as approaching the audience head-on. (Seen in 3D, The Lost City of Z could be 2016’s scariest film.)

The film otherwise bears an echo-heavy sound design reminiscent of and compliant with industrial England’s wide, drafty rooms, a space where the cuts feel most hard-edged and Gray and Khondji appear to have the most fun in photographing. (Such rich black tones! And the light seeping through the windows! And, oh, the candles!) It’s especially easy to get lost in all of this technical what-how when seeing a projection that gives proceedings the look and, on a second-by-second basis, movement akin to a picture of yesteryear, even down to the flickering of an individual image — to the end that I often had little interest in the narrative at hand, despite the best efforts of its cast. Stepping into Fawcett, Hunnam proves so uniformly convincing — as a statesman, as a hunter, as a father and a husband, as an adventurer, as a man of a bygone era — and Robert Pattinson, no doubt a draw when the film is released next spring, displays a selflessness in making tangible the nebbish nature of Corporal Henry Costin. Capable but not much of a hero per se, he’s best remembered for Gray-esque character details: a bushy beard and small glasses that have an effect of shrinking his face to a small patch of skin. But Fawcett isn’t a derring-do type, either. He, like many of the writer-director’s characters, is a man thrown into circumstances beyond his control or understanding — not the least-traveled of narrative paths, but little stressed to make clear any potential precedent.

The circumstances nevertheless have a way of feeling inefficient and intangible, as it so often goes with stories of failure. Percy Fawcett never found the city of zed, instead (likely) dying with his son in the jungle on an expedition in the mid-1920s. When Gray reaches this point, this sense that a life has been spent in danger or waiting — perhaps better realized in a brief World War I trench-clearing battle scene that passes as quickly as it happens, like an experience best forgotten — towards his own effort’s end, the overall intention becomes far clearer, and thus many prior scenes gain a deeper perspective. Best though it is to judge the entire endeavor with this afforded perspective, I found myself having in-the-moment relegations to the image and the sound more than what was being said or where we were being led, and great though my admiration is for the pure craft, I do feel its dramatic backbone is some of Gray’s least-compelling.

If not a substitute for more solid narrative, there is fun to be had in a spot-the-influence game more stongly felt here than in previous films of Gray, who’s never been a cinematic quoter à la many of his more-popular contemporaries. What this and The Immigrant evince is that the presence of others’ voices has been strongest as he’s gone to the past and had more occasion to show what he knows. So the downriver jungle portions may have a bit of Aguirre or The African Queen here; its more hallucinatory night sequences recall his beloved Apocalypse Now; the wide-open pastoral spaces of Fawcett’s later years feel vaguely Ford-esque, in a memory-recalling way that brought to mind How Green Way My Valley. This could just be my film-addled brain doing the talking, but I nevertheless suspect he finds deep meaning in these branches, perhaps evidenced best by a reference to Fellini’s I Vitelloni so specific as to jolt me out of my seat a bit. Applied properly, it strikes as no easy homage — not when the effect is as significant here as it was decades prior.

That might bring me back to the subject of 35mm. Gray’s decision to shoot on the format is, on the surface, insignificant, judging by the fetishization certain corners will readily bestow upon the seven syllables, and its being projected on the format is a nice gesture; but this doesn’t really tell us about the extent to which he (and Khondji) care about it as a storytelling tool. It’s at this last point where The Lost City of Z goes above and beyond what many artists, even talents, possibly could’ve done with this kind of material — at best, a fetish trip through classic adventure pictures, one that cares more about the basic aesthetic dressing than the temperament and still bears no ambition to do anything new. Am I generalizing and spitballing? Absolutely. But the lushness of its images, how they simultaneously recall and move forward, in concert with its confidence in its pacing, as a work of both writing and editing, are a powerful thing taken in-tandem, and it all brings us to a final image I can’t entirely make heads or tails of but will be turning over for some time — a formidable rival to The Immigrant‘s gauntlet-thrower. They don’t make them like they used to, sure. Why should they when we have The Lost City of Z?

The Lost City of Z premiered at the New York Film Festival and will begin its theatrical release on April 14, 2017.