What a deft, lean storyteller this Paweł Pawlikowski has become. The five-year gap between his latest film, teasingly titled Cold War and given a berth in competition at Cannes, and Ida (which premiered in Toronto in 2013 and spent almost two years on the festival circuit) must have felt like an age. Indeed, if there’s one thing we’re never asked to endure in the Polish-born filmmaker’s work, it’s that very nuisance: time. The days and years never drag in his world; instead they seem to skip like a needle across the grooves of a battered record. Cold War depicts a sweeping romance (apparently loosely based on his parents’ relationship, a battered record indeed) that takes us through four countries and almost a decade-and-a-half. It’s 84 minutes long.

Joanna Kulig and Tomasz Kot play, respectively, Zula and Wiktor, two star-crossed lovers who meet in Poland in 1949 when Zula auditions for a folk choir that Wiktor has been hired to conduct. It’s a wonderful introduction. Seemingly coming unprepared, Zula talks another woman into letting her sing harmonies on her tune before launching into her own number, a song she picked up from a Russian musical she once saw at a traveling cinema. Wiktor’s colleague attempts to cut her off but Zula won’t be shackled. We’re maybe 10 minutes in and Wiktor’s already in her grasp.

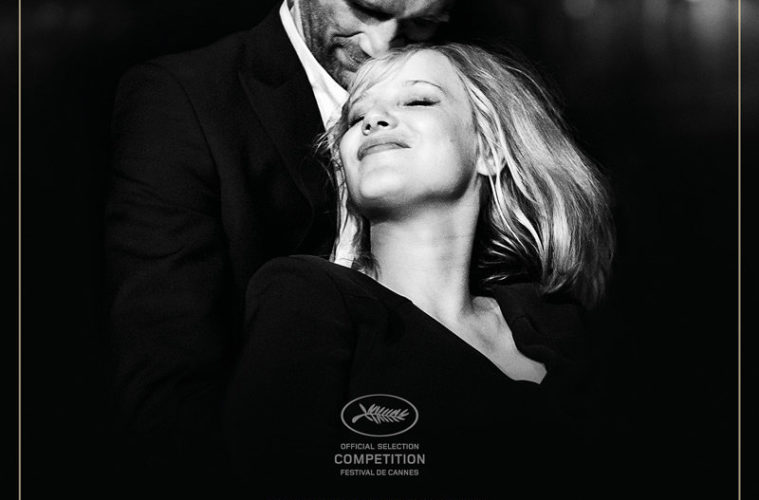

Given Ida’s runaway success, we should forgive — perhaps even commend — Pawlikowski for returning to that film’s rich well of aesthetic confections: the post-war setting, the black-and-white imagery, the “Academy” screen ratio, the folk & jazz music and the glamour. Significantly, Lukasz Zal returns as cinematographer and, just as significantly, comes with a little more cash to burn.

In the film, Wiktor’s choir is a quick success, so they go on the road and Zal shoots their increasingly elaborate performances head-on and with gloriously flat lighting. The results are so dazzling in their retro glamour you feel even Busby Berkeley might have approved. It’s remarkable just how much of the film’s trimmed screen time is given to music (in a beautiful moment we even see Wiktor doing a gig as a soundtrack composer for a ‘50s horror film). If talk is cheap and deceptive — maybe even dangerous at times — in Cold War, music certainly is not.

If the movies have taught us anything, it’s that this time period was not the easiest time for things like love and romance — aka: the most delicious times for love and romance. The local bureaucrats catch the scent of the choir’s imminent success and elbow in with the usual “offer” of dubious support in exchange for some sort of moral bankruptcy (the cold face of Eastern bloc politics, another dip into the Ida well). Echoing this progression, the repertoire of folk songs is sprinkled with blatant propaganda tunes about land reform and Stalin. Flags of the mustached tyrant soon unfurl. A disgusted Wiktor takes off for Paris, crossing a pre-wall Berlin border. Already seduced by her newfound celebrity, Zula dedicates herself to the choir.

The record then begins to skip again, from Poland to Berlin to Paris to Yugoslavia and back again. We witness the arrival of jazz and rock ‘n’ roll in Paris’ late-night clubs, new breeds of music that seem to fuel the film’s best sequences of dance and passion. All the while, we are never made privy to all the nastiness that has possibly taken place in unseen rooms. Did Zulu inform on Wiktor back in Poland? Is it connected to his time in a labor camp? It hardly seems to matter. Indeed, the viewer is only shown Wiktor and Zulu’s brief full-blooded encounters together over the following years — as hairlines recede and the world moves on — and even if the viewers gaze isn’t quite held as strongly in that final third, it is credit to the director’s ability as a story teller that he sees no need to fill in the blanks.

Cold War premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and opens on December 21. Find more of our festival coverage here.