In the director’s statement included in the press notes to It’s Only the End of the World, Xavier Dolan says he considers his sixth feature to be his “first as a man.” Manifestly tired of being called a wunderkind, the 27-year-old follows up his Jury Prize-winning Mommy with an adaptation of the play by Jean-Luc Lagarce. The solemnity aspired to in tackling this contemporary variant of the prodigal son parable is evident, and Dolan delivers a strident transposition of the stage piece to the screen. And while he does, to an extent, stifle some of his more adolescent instincts in comparison to earlier films (e.g. Laurence Anyways and Mommy), Dolan generally appears to have mistaken maturity for joylessness.

In the film’s prologue, the protagonist, Louis (Gaspard Ulliel), is sitting in an airplane and in voice-over explains that he’s returning home for the first time in 12 years to announce his death to his family. Though this cryptic statement is never explicitly clarified, the implication is that he has AIDS – Lagarce died from the disease in 1995, five years after writing the play – and he wishes to reconnect with the family he’s avoided contact with all this time, except for the occasional postcard or letter. Louis hasn’t so much as stepped through the front door, and it’s already abundantly clear why he fled this viper’s nest at the age of 22 — if anything, it’s puzzling that he would have waited that long.

The family is made up of his harpy of a mother (Nathalie Baye), clad in a ghastly outfit and sporting even more hair-raising make-up; his older brother, Antoine (Vincent Cassel), a macho non-achiever with a crippling inferiority complex towards his successful playwright brother; and his younger sister, Suzanne (Léa Seydoux), a chronic stoner harboring serious abandonment issues. Then there’s also Catherine (Marion Cotillard), Antoine’s highly improbable wife, a meek and perennially discomfited presence whose only appreciable purpose in the film is to render the others even more monstrous by comparison.

The family’s idea of a warm welcome is interjecting anyone else’s attempt at a conversation with a barrage of vitriol while Louis stands by, mostly in silence, enduring it all and agonizing over his big reveal. These introductory bouts of invective are broken up by stylized, music-video-like sequences, at times to depict a flashback, at others to evoke more abstract interiority — though, as ever, what they express most forcefully is their creator’s indulgence.

The critic Adam Nayman accurately described the soundtrack to Mommy as “aural torture,” and it initially seems Dolan will be pushing the envelope even further this time around, employing hits by irredeemable bands like Blink-182, Jimmy Eat World, as well as – wait for it – O-Zone’s “Dragostea din tei” (aka the “Numa Numa” song). In the past, Dolan used such teen pop atrocities to amplify his characters’ catharsis, but here they solely come across as an insistently injudicious authorial signature. Mercifully, once the narrative gets properly under way, these are dropped in favor of inoffensive orchestral numbers whose function is much more justifiable.

Namely, underlining the gravity of the situation as Louis engages in the succession of tête-à-têtes that make up the bulk of the film. Mother, sister, and brother each take their turn in discharging 12 years’ worth of pent-up resentment on Louis. Ulliel, who gave such a finely calibrated and effective performance in Betrand Bonello’s Saint Laurent, is wholly out of his depth, sporting a single disconsolate expression from start to finish. That doesn’t seem to be too big a concern for Dolan, though, as the role he’s assigned him is essentially that of a punching bag for the others to pummel with an endless torrent of venom. These shouting matches disallow any emotion other than furious rancor, and the film is unable to offer an exploration of familial strife beyond the purely superficial.

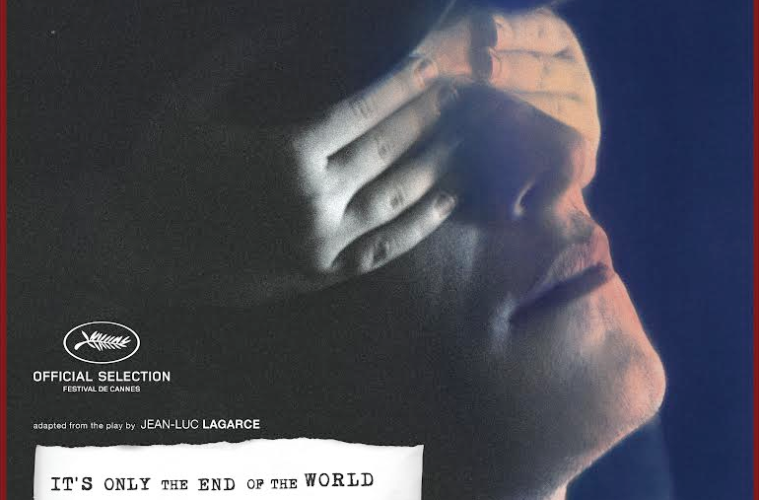

More compelling is Dolan’s choice to construct an adaptation of a play almost exclusively out of tight close-ups of his actors’ faces. The film doesn’t include a single establishing shot and Dolan, who as usual did his own editing, orchestrates careful and dynamic shot-countershot choreographies. Consistently placing his actors with their profiles turned towards the scene’s primary light source, he creates an expressive and prepossessing chiaroscuro on the other half of their faces that provides much-needed elaboration of their internal torment, while the camera’s extreme proximity to the actors creates a stifling theatricality that further fuels the desired oppressiveness of their exchanges.

It’s beyond dispute that it takes talent to make a film this acutely, relentlessly distressing. Why anyone would want to put themselves through such an ordeal, however, is a much more equivocal matter.

It’s Only the End of the World premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and hits Netflix on June 30. See our coverage below.